Apply our problem solving method

Career Wise Menu

Learn problem solving skills: Set Priorities

- Learn to become more strategic at prioritizing your tasks.

- Learn to manage your time better.

“I have so many things on my plate that I feel like I don’t have enough time to complete them all, and I feel like I’m not doing any of them very well.”

“Time is an asset that you are always spending, and it can never be replenished or replaced”

Problems rarely occur in isolation. Perhaps your advisor is not as responsive as you would like, your labmates are not pulling their weight, nothing is going as planned with your equipment, your partner seems distant and resentful lately, and all you want to do is finish your dissertation. You may have defined your problems clearly, but now you’re simply overwhelmed by all of them!

Although you can’t solve everything at once, you can take control over how you will approach the multiple issues vying for your attention. This module will teach you skills to become more strategic and successful at prioritizing your time.

Self-test

Which of the following are true for you?

- A. Answers A, B, & D

- B. When I have lots of things to do, I make rational decisions about which one I should do first based on my priorities for the day.

- C. I have set long- and short-term goals, and I set my priorities on the achievement of these goals.

- D. When I’m working with others on a shared project, I never involve them in prioritizing the workload.

- E. I set long-term goals and then create short-term attainable objectives that I can measure.

Importance is defined as something that gives your life meaning and richness. Things of importance to you (e.g., your career goals) often involve planning and a commitment to achieve and maintain them for the long term. Also remember in the short term that current activities are tied to those goals.

Urgent activities are those that call for immediate attention. Many daily tasks are both urgent and important (e.g., taking your child to the emergency room after she broke an arm or tending to a lab experiment before it is ruined).

The first part of good prioritizing involves spending less time on things that are urgent yet unimportant and more time on tasks that are important but not necessarily urgent. Also, finishing high-priority tasks before taking on lower-priority ones is helpful.

| Important | Not Important | |

|---|---|---|

| Urgent |

Priority ONE Ex: submitting a proposal by the deadline Ex: documenting and reporting a serious sexual harassment incident |

Priority THREE Ex: responding to surveys; social phone calls, e-mails, texts |

| Not Urgent |

Priority TWO Ex: building a professional network Ex: talking to your advisor about how to improve your working relationship |

NOT a priority Ex: reorganizing your closet Ex: volunteering to decorate the TA office |

Note: Only you can decide what you deem important and urgent in your life. While these examples serve as a guide, they do not represent everyone’s truth. So take a moment to reflect on what is most important and urgent in your life.

How much is a given problem getting in the way of your motivation to keep going in your program?

The accumulation of several small stressors and daily hassles that may seem minor can easily build up and become just as insurmountable as one major stressor or problem of grand proportion.

You have probably heard the expression “it was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” referring to the last of a series of small stressors or infractions that eventually became too much to handle. See Stress Triggers.

How much will addressing a certain problem help you professionally and personally in the future? Will addressing it have a great impact or is the problem merely a nuisance of no consequence? For example, if you are struggling with an issue relating to your lab partner, learning to resolve conflicts with teammates will likely be a good skill for your career. See Career Goals and Motivation.

Knowing what is most important to you and making choices accordingly can help put the control back into your hands. Ideally, prioritizing is resolving to act on your terms according to what’s important to you, instead of reacting to every external event that needs your attention. It helps keep you organized and motivated toward reaching your goals.

Try taking a moment to write down what is most important to you this month, from most important to least important. Try not to list any two things as equally important.

Of the pressures you are currently facing, what can’t wait to be dealt with later in the week, later in the semester, or later in your program? What do you think needs to be addressed now, before it turns into an even-greater problem?

It may help to consider how long the problem has persisted. Is it something you have tolerated for the past year and, if so, is there another (more imminent) issue that should be addressed first while the other (more long-standing) issue is tackled afterward?

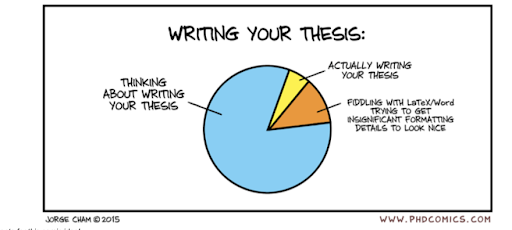

Research suggests you may like to reach short-term goals and solve problems that appear urgent before moving on to something else. The problem in academia is that you will always find yourself dealing with seemingly “urgent” tasks (such as e-mails, doing favors for others, and administrative loose ends).

If you constantly tend to the smaller problems and distractions, you will have a difficult time chipping away at your long-term goals.

Now take a moment to look at the list of what is important to you and think of some problematic issues you are currently facing that match up with these values you listed. Rank the issues by how urgent they appear to be. Consider which issue must be dealt with immediately and which ones are not quite as pressing.

You may discover that one specific concern of yours needs to be dealt with now, before it develops further, while others are not likely to change much despite how bothersome they may be.

How would you sort through the problems in the scenario below, applying what you have just learned about setting priorities?

It’s 6:30 pm on a Tuesday. You can’t stop thinking about a labmate who recently said to you, “Use your head, sweetie.” His disrespectful behavior has started to affect your performance in the lab.

You receive an email from your advisor asking you to complete a project for him by 9 a.m. the next morning. This will mean pulling an all-nighter. He can’t seem to respect the fact that you need sleep.

What’s worse, he hasn’t taken the time to look over the latest draft of your proposal. Looks like you are going to have to keep pushing back your timeline.

Also in your inbox are unanswered messages from your students arguing about their midterm grades and one from your mother asking about your Thanksgiving plans. You think about your long-distance friends and how you never respond to their messages on Facebook. They must think you have fallen off the face of the planet.

Your partner calls to ask where you are. You had promised to go to a happy hour with him to meet his new co-workers.

Here is a task list based on the previous scenario.

Order the tasks below according to number of priority (#1 = highest priority, #7 = lowest priority).

Respond to your emails

1….…2…….3…….4….…5….…6…….7

Reply to your friends on Facebook

1…….2….…3….…4….…5….…6…….7

Attend the happy hour with partner

1….…2….…3….…4….…5….…6…….7

Deal with your frustration toward your labmate

1…….2….…3….…4….…5…….6…….7

Work on your advisor’s project

1….…2…….3….…4…….5…….6……7

Talk to your advisor about respecting your time

1……2…….3……..4…….5…….6……7

Try again to get feedback from your advisor on the proposal

1…….2….…3….…4….…5….…6…….7

Do you find that you rated the items according to your list of what is most important? Remember, some problems might not seem like a high priority. But when you stop to think about what’s at stake, you will realize it is important to deal with this issue right away. For example, if a labmate is hindering your productivity (and your career is of high importance), make it a priority to deal with this problem as soon as possible.

REFLECTIONS: DETERMINING YOUR OWN PRIORITIES

| Important | Not Important | |

|---|---|---|

| Urgent | 1 | 3 |

| Not Urgent | 2 | 4 |

Highly effective people focus their efforts and energy in Box 2. If you are always doing important things in an urgent manner (Box 1), this may reflect two things: 1) You didn’t plan well, so you're doing something at the last minute, and 2) You’re stressed out!

Box 2 indicates that you know what’s important, but you’ve planned well enough not to make it an urgent situation.

See where most of your tasks lie. The Pareto Principle (the 80-20 rule) states that 20% of your tasks determine 80% of your success, and 20% of your tasks are important, while the rest are less consequential. So, be thoughtful about them and prioritize them well.

It may help to think about to whom an activity is important and/or urgent. Consider which 20% of the things on your plate are important to you. If those are also urgent from your point of view, that is where you will want to focus the bulk of your time now.

Remember that prioritizing does not mean that you do not attend to the other matters. Rather, spend less time on them and/or put them off if you can. This might involve negotiating timelines with others. See Negotiation

Other considerations may play a role in deciding which problems to tackle first. Some of these might include:

Control

- The more control you believe you have over a problem (whether it is of importance or not), the more likely you will work toward solving it.

- See Coping & Self Efficacy

The needs of others

- Sometimes you will need to make your needs a priority. At other times you will need to consider the priorities of other people.

- See Stakeholders

- See Consider Other Perspectives

Personality traits

- If you have perfectionist tendencies, for example, you might find it difficult to prioritize at times.

- See Your personality and preferences

- Emotional states

- When you are frustrated with a task, for example, it might be best to walk away from it or work on something else until you calm down.

- See Emotional Styles

Time Management Considerations

Now that you have explored and reflected on your priorities and factors involved in problem solving, we’d be remiss not to include the relevance of time management. Time management is the capacity to estimate how much time one has, how to allocate it, and how to stay within time limits and deadlines. It also involves a sense that time is important.

People tend to overestimate how long it will take to complete short tasks and underestimate the time longer projects will take (called the Planning Fallacy). Individuals who have less power in an organization, like graduate students, are more likely to underestimate time needed for an activity by overlooking areas over which they have less control. Additionally, there's the fact that we forget to schedule time for the basics (e.g., eating, exercising, sleeping).

Consider implementing these tips:

- Make a daily to-do list based on your priorities.

- Audit your time.

- Limit distractions (e.g., social media).

- Start saying “no.”

- Abandon perfection.

- Resist the temptation to assume everything will go smoothly.

- Reward yourself.

Improve Your Time Management through Practice

| If... | Then... |

|---|---|

| You are chronically late getting started on tasks | Focus on starting on time. |

| You get started on time but underestimate how long it will take to do the task | Work on improving time estimation skills within a task. |

| You get lost in whatever you’re doing and don’t make timely transitions between tasks | Work on finishing tasks on time. |

| You have trouble with all three of these. | Choose one recurring task or activity and focus on all three in your long-term plan. |

Additionally, consider the Pomodoro Technique:

- Choose the Task.

- Set a timer for 25 minutes.

- Work on the task until the timer beeps.

- Take a short break of 3-5 minutes.

- Repeat the cycle 4 times and take a longer break after 4 sessions.

Ultimately, it is important you find a system that works for you by experimenting with different schedules and techniques.

Procrastination

Do you have responsibilities and assignments that have approaching due dates? Do you resist acknowledging the to-do list that’s been staring at you from the corner of your desk for months? Maybe you’ve also been putting off that meeting with your lab manager? If this sounds familiar, join the crowd.

Don’t worry, you’re not alone. Procrastination is the tireless force pushing us to put off completing a task and is characterized by the common refrains: “I’ll do it tomorrow” or “I work better under pressure.”

In graduate school, putting off important activities can seriously impact your progress. However, there are strategies you can implement to reduce procrastination habits.

Reduce Your Procrastination through Practice

| If... | Then... |

|---|---|

| You fear failure and being judged | Focus on managing your perfectionist standards and adopting flexible and realistic expectations. |

| You often day dream and find yourself easily bored by tasks | Set up a ritual to get in the right frame of mind before taking action, such as doing a minute of breathing exercises; making yourself a warm, soothing drink; or tidying your desk. |

| You postpone tasks that threaten your feelings of autonomy | Write a list of positive emotions you’ll feel as a result of taking action: “I’ll feel liberated;” “I will have a clear conscience;” or “I’ll save time for something fun.” |

| You put off tasks that you should have declined | Learn to say “No.” |

| You are a people pleaser who tends to overcommit | Learn to set healthy boundaries. |

| You prefer playing over working | Schedule your playtime as a reward for getting priority tasks done. |

Make it a weekly habit to think about what’s really important to you. It will make prioritizing your activities much easier.

In the end, setting priorities is an exercise in self-knowledge. You need to know what activities lead to your objectives and which ones lead you astray. Remembering why you love what you do will keep you motivated.

Aeon, B., Faber, A., & Panaccio, A. (2021). Does time management work? A meta-analysis. Plos one, 16(1), e0245066. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245066

Covey, S. R. (1989). The seven habits of highly effective people: Restoring the character ethic. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Covey, S. R., Merrill, A. R., & Merrill, A. A. (1994). First things first. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Deemer, E., Smith, J., Carroll, A., & Carpenter, J. (2014). Academic procrastination in STEM: Interactive effects of stereotype threat and achievement goals. The Career Development Quarterly, 62(2), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2014.00076.x

Guinote, A. (2007). Power and goal pursuit. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(8), 1076–1087. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207301011

Kearns, H., Gardiner, M. & Marshall, K. (2008) Innovation in PhD completion: The hardy shall succeed (and be happy!), Higher Education Research & Development, 27(1), 77-89, https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360701658781

Macan, T. (1994). Time management: Test of a process model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(3), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.79.3.381

Roster, C., & Ferrari, J. (2020). Time is on my side—or is it? Assessing how perceived control of time and procrastination influence emotional exhaustion on the job. Behavioral Sciences, 10(6), 98–. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10060098

Schraw, G., Wadkins, T., & Olafson, L. (2007). Doing the things we do: A grounded theory of academic procrastination. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.12

Steel, P., & Klingsieck, K. (2016). Academic procrastination: Psychological antecedents revisited: Academic procrastination. Australian Psychologist, 51(1), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12173

Weick, M., & Guinote, A. (2010). How long will it take? Power biases time predictions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(4), 595–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.03.005

Zhu, M., Yang, Y., & Hsee, C. (2018). The mere urgency effect. The Journal of Consumer Research, 45(3), 673–. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucy008

The importance of defining clear goals, remaining self-confident, and learning to say no.

The importance of allowing yourself the opportunity to change your mind and reconsider your goals.

Outlines a philosophy on time management.

Dealing with Assumptions and Accusations

Being accused of cheating and regrets about not being more assertive.

Creating an Environment for Exchanging Ideas

How the physical space in a laboratory allowed for collaboration among colleagues.

The satisfaction that comes from working with colleagues and interacting with others.

Pursuing Different Threads in Career Positions

Contributions to the field are reflected through choices.

Compromises Outside the Realm of Children

Addresses personal relationship sacrifices.

Apply Problem Solving Side Menu

“It is not enough to be busy; so are the ants. The question is: What are we busy about?”

“Feeling productive is not about adding more things to our to-do list. It’s about eliminating the unnecessary so that we have time to focus on what is most important.”

An Arizona State University project, supported by the National Science Foundation under grants 0634519, 0910384 and 1761278

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. © 2021 CareerWISE. All rights reserved. Privacy | Legal