Identify the issue: Challenges faced by first-gen students

Example hero paragraph text.

Learn to identify different resources available to first-generation college students.

Learn to identify characteristics of first-generation students.

Learn to recognize the common barriers first-generation students experience.

Learn persistence strategies linked to first-generation student success.

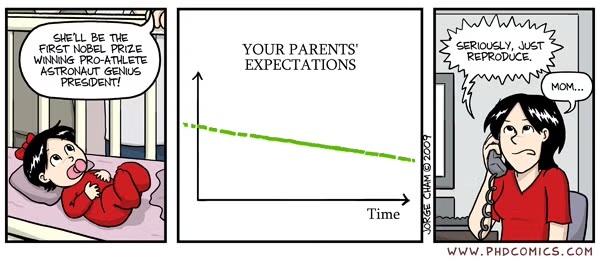

“ I have to finish–I owe it to my parents.”

“Don’t live down to expectations. Go out there and do something remarkable.” – Wendy Wasserstein

“Demography is not destiny.” – Engle & Obrie

The start of a graduate program is a time when students are initiated into a new culture and are expected to embrace a new identity. As a new doctoral student you may find yourself playing catch-up with more advanced students and feeling as if you have to learn a new set of rules (see Expectations for Graduate Students). At the same time, you are learning new ways of thinking and are becoming a member of the academy, a scholarly community.

The term “first-generation student” refers to a student whose mother and father have no more than a high school diploma and who is the first in their family to go to college” educational attainments are at or below a high school diploma and who is the first in their family to go to college. Demographics show that many low-income, first-generation students tend to be older and female, are from underrepresented minority backgrounds, have dependent children, learned English as a second language, and are financially independent from their parents.

Consider the following statistics (NCSES, 2020) :

- The proportion of doctorate recipients who were first-generation college students fell from 30% in 1994 to 16.5% in 2020.

- The proportions of first-generation doctoral students are higher for racial/ethnic minorities: The fathers of 42% of Black or African-American and 35% of Hispnaic/Latino first-gen doctoral students have a high school diploma or less.

- Approximately 1 in 4 women who completed a doctoral program are first-generation students.

The integration of first-generation students brings an important element of diversity to the academy. A diversity of backgrounds and perspectives contributes to a broader educational experience that helps prepare students to participate more fully in a civil society. Diversity enriches the academic community in many ways, by promoting awareness and understanding, increasing levels of service, and enhancing critical thinking abilities among the group’s members. Ensuring diversity among students, including gender, ethnicity, and the student’s family’s educational background, helps universities fulfill the mission of preparing students to become active citizens in an increasingly global society.

As a first-generation student, you may have experienced one or more of the following barriers:

- Less support and encouragement from family

- Fewer or no role models of people who have gone through graduate studies

- Fewer social connections and more isolation

- Perceptions and/or intimations that you wouldn’t or don’t fit in higher education because of your social identity or multiple social identities

- Less knowledge about how to select a school that is appropriate for your goals and interests

- More concerns about financing your education

- Less academic preparation

- Multiple memberships in other marginalized groups (e.g., race, income, gender)

- Learning to work with faculty who may not recognize that all students may not understand university culture or institutional expectations

Some constraints for low-income, first-generation students are also worthy of mention, such as:

The need to attend to responsibilities beyond graduate school such as helping to support your family, i.e., parents and/or siblings, children and the need to be employed while attending school.

Changes in relationships with family members and long-time friends as interests and commonalities become diluted.

Family and friend’s failure to understand your continuing workload when you go home for a break. For example, families may not understand why you are still reading and writing papers while on “break.”

The university setting has its own “culture,” or way of life, with norms and expectations as well as customs and shared knowledge that students master with experience. Students with college-educated parents have cultural and social capital that puts them at an advantage over students who do not have the family experiences to rely on when they embark on their journey through academic life. Simply put, this “capital” refers to the benefits and resources that are transferred to students within their family relationships. These social and cultural advantages give students a more solid start to higher education.

By comparison, first-generation students face unique challenges, as they are less likely to have been well versed in the culture of academic life and the pursuit of opportunities in graduate education. First-generation students frequently come from humble backgrounds without such capital and therefore are more likely to enter higher education at a disadvantage to others.

Students with the benefits of social and cultural capital are more likely to know how to talk with a professor about feedback or grades.

- Negotiate gaining a mentor (see What you Want in an Mentor)

- Find financial aid and/or research or teaching assistantship.

- Write a graduate thesis or paper for publication.

When such help and information are not available within one’s family circle, it is important to take an active role in seeking out resources (see Be Resourceful module) such as connecting with a mentor and becoming involved with professional groups, student organizations, and online professional networking options (see Online Resources and Supports and University Resources for Graduate Students modules).

If you are the first in your family to attend graduate school, you have already demonstrated personal strengths and resilience (see Resilience module) by overcoming barriers during your undergraduate career and getting into graduate school. You may find yourself drawing upon these strengths (see Build on Your Strengths module) such as:

Reminding yourself of the many times you have overcome obstacles in the past.

Taking pride in your accomplishments and feeling empathy toward others as you adjust to the academic culture of graduate school.

Building on motivational factors such as becoming the first “doctor” in your family and wanting to finish what you started.

Believing that you can be successful and viewing academic tasks as important and useful to increase academic success.

Self-test

First generation students are more likely to:

- A. Know how to find financial aid or a research/teaching assistantship position

- B. Have more concerns about financing their education

- C. Have fewer or no role models of people who have gone through graduate studies

- D. B & C

D is the correct answer,

Students with college-educated parents have cultural and social capital that puts them at an advantage over students who do not have the family experiences to rely on when they embark on their journey through academic life. Thus, students with college-educated parents are more likely to experience A. By comparison, first-generation students face unique challenges, like B and C, as they are less likely to have been well versed in the culture of academic life.

First-generation students tend to be less engaged in social networks and have fewer support among their peers. However, research also suggests that these individuals benefit more from extracurricular programs and activities than do students whose parents have attended college (Pascarella et al., 2004).

If you are a first-generation student, it is important for you to act on opportunities to network with peers and colleagues and to get involved as much as possible in research activities, student organizations, study groups, etc., in order to acclimate to the academic culture of your graduate program. Colleagues and mentors can also help you navigate campus resources and financial aid, share study skills and research tips, and can aid you in planning for future careers.

In order to give you the edge you need to persist through graduate school, there are a number of strategies you might consider, such as:

Talking with your advisor or a mentor about gaps in your knowledge about the processes of graduate school—it may help for them to know that you feel you are blazing this trail alone and may not have anyone to look to for support or with questions that come up. Your advisor or mentor may not know you do not have support because in contrast to ethnicity and gender, which are visually apparent, being a first-generation student is a hidden social identity, similar to class or sexual orientation.

Being engaged in academic and course-related activities with faculty members and other students.

Realizing you are not alone, nor are you the first person attempting doctoral work with your background.

Finding a mentor. This could be an older student who has graduated from your program and moved on and likely understands the challenges and nuances of your program or someone in your field’s industry. This may even be someone outside your field of study or from your undergraduate experience.

Make widening your informal and formal support system a top priority. Having people with whom to celebrate or commiserate will help you feel much more comfortable in your new environment.

Locating graduate student organizations that may have a first-generation component. Ask members what was particularly helpful. These organizations may also give you the opportunity to share information you’ve acquired with other first-generation students. This may already exist through national or local organizations such as a graduate women’s association or Women in Science and Engineering (WiSE).

First-generation students should be resourceful (see Be Resourceful Brief) and seek out opportunities that are available. Some examples are:

- The McNair Scholars Program (www.mcnairscholars.com) is a national scholarship program supporting first-generation students and other underrepresented minorities who are pursuing doctoral degrees. It has a strong mentoring component.

- The National Association of Graduate-Professional Students (http://www.nagps.org/) is an organization dedicated to helping improve graduate student life.

- The American Association for University Women (AAUW; www.aauw.org):

- Funds several scholarships and grants

- Has useful information at its website on how to connect with peers and make your voice heard.

- Is committed to “breaking through barriers for women and girls” and offers a plethora of information and ways to get involved.

- The Association for Women in Science (AWIS; http://www.awis.org/):

- Funds scholarships and grants.

- Focuses on promoting equality and advocacy for women in the sciences and math.

- Provides information on networking and other professional opportunities at its website.

- Published a resource that includes dozens of personal stories: A Hand Up: Women mentoring women in science.

Consult the Online Resources and Supports module for an extensive list of additional resources.

Engage in academic and socialization experiences such as being mentored through research projects and at conferences, taking coursework with faculty who have similar social identities, and participating in informal settings such as meeting for coffee. All of these can be critical to success in graduate school.

As solitary as the doctoral process can be, remember you are not alone, and more likely than not, others have blazed the trail before you. Seek them out for support and information to successfully complete your program.

Cataldi, E. F., Bennett, C. T., & Chen, X. (2018). First-generation students: College access, persistence, and post bachelor’s outcomes. Stats in Brief. NCES 2018-421. National Center for Education Statistics. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED580935

Chang, J., Wang, S. W., Mancini, C., McGrath-Mahrer, B., & Orama de Jesus, S. (2020). The complexity of cultural mismatch in higher education: Norms affecting first-generation college students’ coping and help-seeking behaviors. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 26(3), 280. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000311

Crumb, L., Haskins, N., Dean, L., & Avent Harris, J. (2019). Illuminating social-class identity: The persistence of working-class African American women doctoral students. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 13 (3), 215-227. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000109

Gardner, S. K. (2013). The challenges of first‐generation doctoral students. New Directions for Higher Education, 2013(163), 43-54. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.20064

Gardner, S. K., & Holley, K. A. (2011). “Those invisible barriers are real”: The progression of first-generation students through doctoral education. Equity & Excellence in Education, 44(1), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2011.529791

Garriott, P. O. (2020). A critical cultural wealth model of first-generation and economically marginalized college students’ academic and career development. Journal of Career Development, 47(1), 80-95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845319826266

Gittens, C. B. (2014) The McNair Program as a socializing influence on doctoral degree attainment. Peabody Journal of Education, 89(3), 368-379. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2014.913450

Holley, K. A., & Gardner, S. (2012). Navigating the pipeline: How socio-cultural influences impact first-generation doctoral students. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 5(2), 112-121. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026840

Kniffin, K. (2007). Accessibility to the PhD and professoriate for first-generation college graduates: Review and implications for students, faculty, and campus policies. American Academic, 3, 49-79.

Leyva, V. L. (2011). First‐generation Latina graduate students: Balancing professional identity development with traditional family roles. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2011(127), 21-31. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.454

Ma, P. W. W., & Shea, M. (2019). First-generation college students’ perceived barriers and career outcome expectations: Exploring contextual and cognitive factors. Journal of Career Development, 48(2), 91-104. https://doi.org/0894845319827650.

National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES). 2020. Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Universities: 2019. NSF 21-308. Alexandria, VA: National Science Foundation. Available at https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf21308/.

Pascarella, E. T., Pierson, C. T., Wolniak, G. C., & Terenzini, P. T. (2004). First-generation college students. Journal of Higher Education, 75, 249–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2004.11772256

Rendón, L. I. (2020). Unrelenting inequality at the intersection of race and class. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 52(2), 32-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2020.1732772

Roksa, J., Feldon, D. F., & Maher, M. (2018). First-generation students in pursuit of the PhD: Comparing socialization experiences and outcomes to continuing-generation peers. The Journal of Higher Education, 89(5), 728-752. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2018.1435134

Tate, K. A., Fouad, N. A., Marks, L. R., Young, G., Guzman, E., & Williams, E. G. (2015). Underrepresented first-generation, low-income college students’ pursuit of a graduate education: Investigating the influence of self-efficacy, coping efficacy, and family influence. Journal of Career Assessment, 23(3), 427-441. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072714547498

Turner, C.S.V. & Thompson, J.R. (1993). Socializing women doctoral students: Minority and majority experiences. The Review of Higher Education, 16(3), 355-370. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.1993.0017

Challenges with being married to a fellow academician and finding faculty positions.

Becoming an Independent Voice as a Young Faculty Member

The process of establishing yourself in the same department as your spouse.

Urges students not to get wrapped into issues that do not directly involve them.

The Importance of Sharing Stories

The importance of hearing other people’s stories.

The first realization that being a woman in science was outside the norm.

Words of Wisdom from Dr. Chattopadhyay

Advice for graduate students on how to maintain their confidence, courage, and dignity.

Being Comfortable as a Woman Among Men

Emphasizes positive peer relationships within her cohort.

Incidents of Prejudice Due to Married and Pregnant Status

Gender stereotypes faced in getting into graduate school and conducting research.