Apply our problem solving method

Career Wise Menu

Learn problem solving skills: Interpersonal Communication Styles

- Learn to recognize differences in communication styles

- Learn how interpersonal communication styles can affect relational outcomes.

- Learn how to use the Interpersonal Circle to adapt your interpersonal communication style to the situation.

“They may forget what you said, but they will never forget how you made them feel.” —Carl Buechner

“The most important single ingredient in the formula of success is knowing how to get along with people.” —Theodore Roosevelt

Do you notice that you act in different ways around certain people? Perhaps you act inhibited around your advisor but act self-assured around your students. Maybe you wish you could be as sociable with your labmates as you are so easily around your friends. These descriptors: inhibited, sociable, assured, and deferent are all examples of interpersonal communication styles (Kiesler, 1982).

This module is designed to address the interpersonal communication styles that you bring to a communication interaction. The more you know about interpersonal communication styles, the more you can deliberately choose to use a style or not, depending on the situation.

The concepts of interpersonal communication styles and personality overlap, but they do not mean the same thing. People often say “that’s just the way I am.” However, interpersonal communication styles are actually changeable and more in your control than you might think.

Think back to a time in which you communicated with someone and by virtue of the initial interaction you developed a new approach that you tried the next time. For example, perhaps when talking with your advisor you were reserved and didn’t speak up when someone was getting recognition for your work; the next time the topic of work credit came up you were more assertive and spoke up for yourself.

The fact that you are able to change your approach, and essentially the impression you make (see The Impression You Make), are different from personality. Personality is more steady and consistent and is most often viewed in terms of traits—a stable, enduring quality that a person shows in most situations (i.e., who we are)—rather than a behavior (i.e., how we act). [See Your Personality and Preferences for more.]

One of the interesting things about interpersonal communication styles is that they can be specific to a situation (e.g., you are different around a faculty member) or defined by how you behave in most communication situations (e.g., you are sociable with most people). You can choose when to use the interpersonal communication style that best serves you in the situation.

Over time, recognizing and selecting which interpersonal communication approach you wish to use in a particular instance will become easier. With practice the ability to choose will help you break the patterns that don’t work for you in certain situations.

There are many different approaches to defining interpersonal communication styles. Here we describe a couple of models that have received ample research support. We focus on the Interpersonal Circle and its accompanying theory, “Complementarity.”

There are many different approaches to defining interpersonal communication styles. Here we describe a couple of models that have received ample research support. We focus on the Interpersonal Circle and its accompanying theory, “Complementarity.”

The Interpersonal Circle

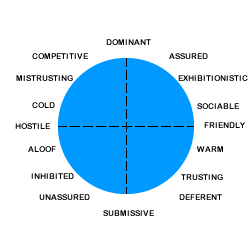

Interpersonal theorists (Carson, 1969; Kiesler, 1983; Leary, 1957) created the Interpersonal Circle to explain the ways in which people relate to each other interpersonally. The model is based on a system of similarity and dissimilarity and is meant to explain and predict the ways in which two different people may interact in a given situation.

In this model, 16 interpersonal styles are positioned around a circle. Interpersonal theory has been applied both to traits and behaviors. Here we discuss its applications to real-time communication exchanges of individuals in a dyadic interaction.

The model represents a system that charts interpersonal communication across two dimensions: Power and Affiliation. In the model, the Power (Dominance) axis runs vertically. On this dimension, those interpersonal styles positioned directly across from each other are viewed as complementary to each other.

In practice, this would mean that in a given interpersonal interaction, individuals who act in a dissimilar manner on the Power axis would likely get along well with each other. For example, if one individual were to act in a dominant manner, then the behavioral response that would likely lead to the best outcome would be for the other person to respond with deference. This makes sense if you consider how the alternative might play out—that is, two people competing for dominance.

The Affiliation axis runs horizontally. Contrary to the Power dimension, similarity is complementary on the Affiliation dimension. For example, if one person acts in a friendly manner, then the responses that would likely predict the best outcome would be for the second person to respond in an equally friendly, warm or sociable manner.

There are multiple reasons why the interpersonal circle is relevant to your life. Using the interpersonal circle is a relatively simple way to identify your own tendencies toward particular styles with certain individuals. There is evidence that those who view the social world using a structure similar to that of the interpersonal circle report fewer interpersonal problems and higher levels of satisfaction with life, self-confidence, and self-liking.

Complementarity

The powerful theory that arose from the Interpersonal Circle is complementarity. Complementarity is the idea that individuals interact in a manner that elicits a restricted class of behaviors (e.g., dominance requests submission and friendliness invites similar behaviors) and you have the choice to either act in a complementary fashion or not.

The degree to which another individual complements those behaviors has some predictive utility for measuring how well the relationship will go. The deliberate choice to complement or not is called Complementarity.

The theory suggests that certain behaviors “pull” particular responses from the other person. Being friendly generally elicits friendliness from the other person. Complementary behaviors on the friendliness (affiliation) axis generally indicate better communication and mutual liking.

If you as a student approach a colleague or a professor in a friendly manner, you are more likely to get a friendly response. If a faculty member is friendly in your exchange and you respond in a chilly manner (maybe you had a bad day or you are unhappy with the professor), the (anticomplementary) interaction will probably be uncomfortable and set a negative tone.

Another example of complementarity could be that your professor treats his students in a dominant manner. This dominance sends the message that the professor sees himself as having power and that he expects his students to submit to his behaviors. If you understand this dynamic and view his interpersonal behavior in this manner, you can make a deliberate choice to complement this behavior or not complement this behavior.

In this case, complementing would mean that you validate the professor’s interpersonal message by being more deferent. Not complementing might mean responding in an assured manner by communicating that you have opinions or knowledge about the topic, work, etc. and you will not merely submit to the professor’s interpersonal message.

Neither response is inherently bad, but each response above carries consequences with it. If you submit, you may not have your voice heard or you may not have important decisions go the way you’d like. Implying to this professor that you consider yourself to be on the same level as they are may not go well.

However, if you do not submit, it might lead to a power struggle with your professor, which is never an ideal situation for any graduate student. The point is to recognize the interpersonal messages people send and to make deliberate decisions about when to complement those messages and when not to do so.

Be aware: if you are redefining your interpersonal approach with an individual who is used to you acting in a particular manner, there might be a period of discomfort, or even backlash, as they adjust to your new way of conducting yourself. Although the time of adjustment is often uncomfortable, it is quite normal. Stick with it, if that is your preferred path.

Self-test

Consider the example of a professor who spouts orders, asserts himself as dominating, and expects his students to be subservient. He considers his research assistants to be personal assistants and sends them on personal errands and expects them to be available at all hours of the day and night.

Which graduate student response would be complementary to his behavior?

- A. Submitting by way of obeying all orders and never asserting yourself.

- B. Responding in an assured manner by communicating that you have opinions, knowledge, and boundaries, and you will not merely submit to the professor’s interpersonal message.

Think of someone with whom you have trouble communicating. Once you have that person in mind, use the interpersonal circle to identify that individual’s interpersonal communication style.

How would you choose to complement or not complement their style? Is there anything you want to change about how you would approach your communication with that person? How does the model help you think about this?

Marissa works in a lab with three labmates. One labmate, Liang, treats Marissa as if she were the lab mom. He asks her to order supplies, to clean up, to order lunch for the group during working meetings, etc.

Marissa usually complies with Liang’s requests. That is, she usually complements Liang’s dominant interpersonal communication style with a submissive interpersonal communication style.

However, she wants very badly to change her dynamic with Liang so he stops bossing her around. The following interaction is one in which Marissa deliberately chooses not to complement Liang’s interpersonal style in order to change their interpersonal dynamic.

Remember, when thinking interpersonally, the way in which you deliver the message through nonverbals and the words you choose are equally if not more important than the content of the discussion. Let’s see how Marissa does.

LIANG: [walking up to Marissa, while she’s working] Marissa, we are out of toner and paper and I need to print these results. Can you go to the department secretary and see if they have some we can use and then order more. [Liang’s interpersonal communication style is best defined as dominant: he is making demands and bossing Marissa around]

MARISSA: [continuing to work] Sorry, Liang, I’m busy. You’re going to have to go yourself. [now making eye contact with Liang]. Also, I think it’s time someone else in the lab besides me orders supplies. If you need help figuring it out, I am happy to help, but I’m relieving myself of the responsibility of ordering things for everyone. I have a lot of work to do before I graduate and I’ve done my fair share—it’s someone else’s turn. [Marissa’s interpersonal communication style here is assured].

LIANG: [caught off guard and looking perplexed] What is this? Are you upset because I didn’t say “please” and “thank you”? [Liang meets Marissa’s assured interpersonal message with a stronger form of dominance]

MARISSA: [stopping what she’s doing, turning to face Liang and deliberately using a calm voice that does not convey hostility]. Liang, a “please” or a “thank you” would have been nice, but this isn’t a reaction in the moment. I’ve given it some thought and I have decided it’s time someone else takes care of ordering things around here. [Marissa continues to use an Assured interpersonal communication style and stays on message]

LIANG: [now clearly frustrated] We’ll see how this goes. I don’t have time for this [Liang walks away]

MARISSA: I don’t either, Liang. That’s the point.

Let’s debrief:

Marissa deliberately chose to not complement Liang’s dominant interpersonal communication style, both in the words she chose (e.g., I have decided it’s time someone else takes care of ordering things around here.) and the nonverbals she conveyed (e.g., making eye contact instead of staring down at her work).

In the face of Liang’s persistence in expecting that she did what he wanted, Marissa stuck to her message while also communicating that she wasn’t looking for a hostile confrontation.

There are some elements of this interaction that would likely play out in most similar situations:

- When people send an interpersonal message that is not validated by the other person, they usually try to send the message again, only this time with more intensity. Liang did this by becoming even more dominant and attacking Marissa on an interpersonal level, when he said, “is this because you didn’t get a “please” or “thank you”?

- When Liang began to send a stronger dominant message, Marissa likely felt uncomfortable. When faced with this type of discomfort, most people give up and return to submissiveness or, conversely, they meet the other person’s attempt at dominance with hostility or a dominant message of their own—essentially, they tell the person, “you are not in charge,” but they do so in a hostile or confrontational way. Marissa anticipates this and stays on message while also communicating that she is not looking for a hostile confrontation.

- Marissa was also very effective at keeping the interaction in the “here and now” instead of talking about past incidents.

- Marissa also used “I” statements such as “I can’t do this” and “I’ve made a decision.” Many people unintentionally sabotage their interaction by putting things on other people by making statements like, “you’re bossy” or “you just want to boss me around.” These types of accusations are almost impossible to prove in the moment and usually turn into an argument. By avoiding these types of statements, Marissa avoids a whole other area of interaction that would most likely turn into an argument.

Carson, R. C. (1969). Interaction concepts of personality. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Co.

Cheng, C., Wang, F., & Golden, D. L. (2011). Unpacking cultural differences in interpersonal flexibility: Role of culture-related personality and situational factors. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42(3), 425-444. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022110362755

Fan, H., & Han, B. (2018). How does leader‐follower fit or misfit in communication style matter for work outcomes? Social Behavior and Personality, 46(7), 1083–1100. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.6925

Gifford, R. (1991). Mapping nonverbal behavior on the Interpersonal Circle. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.279

Graham, K., Mawritz, M., Dust, S., Greenbaum, R., & Ziegert, J. (2019). Too many cooks in the kitchen: The effects of dominance incompatibility on relationship conflict and subsequent abusive supervision. The Leadership Quarterly, 30(3), 351–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.12.003

Kiesler, D. (1983). The 1982 Interpersonal Circle: A taxonomy for complementarity in human transactions. Psychological Review, 90(3), 185–214. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.90.3.185

Kurzius, E., Borkenau, P., & Leising, D. (2021). Spontaneous interpersonal complementarity in the lab: A multilevel approach to modeling the antecedents and consequences of people’s interpersonal behaviors and their dynamic interplay. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Advance Online Publication. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/10.1037/pspi0000347

Leary, T. (1957). Interpersonal diagnosis of personality. New York: John Wiley & Sons

Locke, K. (2019). Development and validation of a circumplex measure of the interpersonal culture in work teams and organizations. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 850–850. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00850

Mainhard, T., Van Der Rijst, R., Van Tartwijk, J., & Wubbels, T. (2009). A model for the supervisor-doctoral student relationship. Higher Education, 58(3), 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9199-8

Markey, P., Lowmaster, S., & Eichler, W. (2010). A real‐time assessment of interpersonal complementarity. Personal Relationships, 17(1), 13-25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01249.x

Moskowitz, D. S., Ho, M. R., & Turcotte-Tremblay, A.-M. (2007). Contextual influences on interpersonal complementarity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(8), 1051–1063. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207303024

Orellana, M. L., Darder, A., Pérez, A., & Salinas, J. (2016). Improving doctoral success by matching PhD students with supervisors. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 11, 87-103. https://doi.org/10.28945/3404

Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. New York: W.W. Norton.& Company.

Tracey, T. (1994). An examination of the complementarity of interpersonal behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(5), 864–878. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.5.864

Wiggins, J. (1979). A psychological taxonomy of trait-descriptive terms: The interpersonal domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(3), 395–412. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.3.395

On Speaking Up: A Conference Experience

Confronting a male colleague with contradictory findings at a conference.

Highlights the obstacles faced when trying to have research reviewed by the advisor and emphasizes the steps necessary to make adequate progress in the program.

Captures the annoyance of male colleagues making sexist assumptions and the challenges with conference travel as a female graduate student.

Suggestions for defining research.

I Have Not Figured Out How to Say "No"

Emphasizes the challenge with saying no, but the importance of learning to do so.

Asserting Yourself in the Face of Authority

The importance of standing up for yourself.

Paths of Family Planning and Different Options Along the Way

How a flexible schedule as a professor made it possible to have a family and a career.

Proactive Approach and Adapting Environments

How to adapt experimental methods to match a lifestyle.

Apply Problem Solving Side Menu

An Arizona State University project, supported by the National Science Foundation under grants 0634519, 0910384 and 1761278

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. © 2021 CareerWISE. All rights reserved. Privacy | Legal