Communicate More Effectively

Career Wise Menu

Learn Communication Skills: Plan the Message

- Learn to identify the goal of your message.

- Learn to gather useful information to plan your message.

- Learn to choose a channel and mode of delivery.

- Learn to prepare yourself for instances of unplanned or unexpected communication

As a graduate student, time is probably something you don’t have in great quantity. Allotting extra time for basic communication tasks like emails, phone calls, and even face-to-face meetings may even be an annoyance.

However, taking a few moments to consider and prepare a well-crafted message will help you communicate most effectively with the limited amount of time you have. It will promote higher quality interactions and eliminate instances of miscommunication.

Now, more than ever before, we have multiple options for communicating—from email, instant messaging, text, social media, web meeting tools like Zoom, Skype and FaceTime, to the conventional phone and face-to-face.

Choosing which medium is most appropriate is not always clear. Some choices fall to personal preference—both yours and the other person’s—but there are some basic communication principles that, if employed correctly, may prove invaluable when making the choice about when and how to communicate your message.

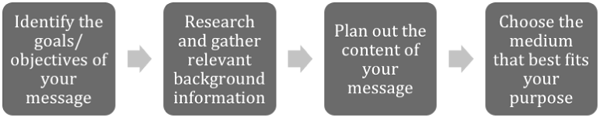

For the purposes of this module, we use the following structure for planning your message:

Being able to identify the goals and objectives of your communication interactions and translate them into a well-planned message is usually the first step toward achieving successful communication outcomes. Whenever we communicate, there are consequences, whether we intend them or not.

For example, what and how we communicate may impress or frustrate a supervisor, engage or discourage a partner, build or diminish a friendship, or succeed or fail in eliciting specific guidance for an assignment. Identifying in advance of communicating which of these outcomes you’re reaching for or want to avoid enables you to plan how best to structure and deliver your message.

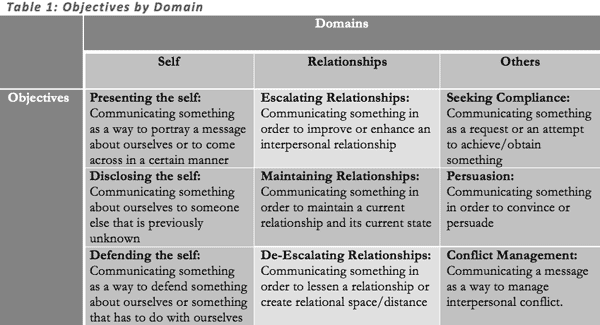

It is helpful to think of interpersonal communication goals in three domains: how you want to present yourself, what you want from others, and what you want your relationship to be. The following table provides some examples of objectives by domain.

In many situations you may have multiple objectives that tap more than one domain. In fact, communication goals typically have both a relational and a task element. It is almost always important to consider the impact your message will have on your relationship with the other person when you’re planning to communicate in the self or other domains.

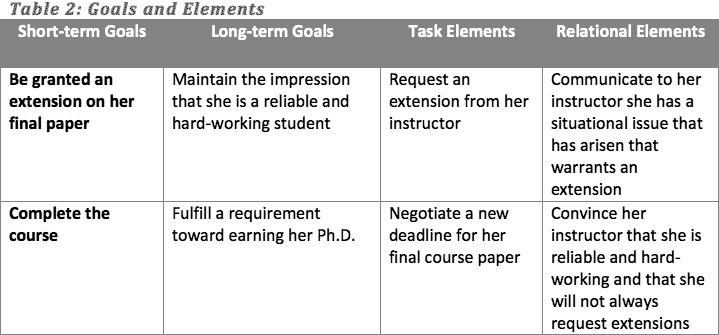

In addition to tapping more than one domain, objectives can be short or long-term. They are usually multidimensional. As an illustration of this complexity, consider the following scenario to see how you can begin to break down a seemingly one-dimensional issue into a multifaceted and interrelated series of concepts:

Rochelle has an issue that has arisen in her personal life during finals week that is preventing her from finishing the final paper in one of her courses. Since she is only in the second semester of her program, she is worried that a request for some flexibility may be viewed negatively and may be shared with the faculty in her program. She knows that her overall communication goal is to convince her instructor that she needs extra time to complete the assignment. In fact, if you asked Rochelle to identify her communication goal she might identify only this one main goal, but upon further analysis she may recognize multiple goals at multiple levels. The following table shows what they may be.

Reflecting upon and identifying these multifaceted goals is relevant and important because if Rochelle simply writes and says, “I have an issue that has arisen in my personal life. May I please be granted an extension on my final paper,” her instructor will be left with little information and will likely fill in the missing information because of its absence.

Conversely, if Rochelle identifies the goals of the message in advance and adjusts the message accordingly, her instructor will be left with a very different impression of the situation. For example, imagine that Rochelle decides to email her instructor the following message:

Dear Professor Khurshid,

A personal situation has come up that is conflicting with my ability to complete the final paper in your course by the deadline. I am writing to request an extension of four days so I may complete the assignment and your course in a timely manner and before final grades are due. I realize this may be an inconvenience to you and I apologize in advance. Please know that I would not request this extension if the issue was not one that warranted the request. If you recall I have submitted all other assignments in the course in advance of the due dates and I have received excellent grades for each assignment. I look forward to your response. Please let me know if you have any questions or concerns.

Thank you for your consideration.

Rochelle

Notice that Rochelle has touched upon all of the goals identified above without having to share too much personal information and without having to point out each of the goals explicitly in her message. Likely her message will be received knowing what she is requesting and how this fits into the greater pattern of her behavior as a student.

This example interaction is fairly straightforward and has likely been somewhat easy for you to imagine navigating; however, not all communication interactions are so clear. There are times when you can inadvertently share information or impressions that are unintentionally harmful.

When considering goals for the message you want to communicate, it is also essential to understand the messages you do NOT want to communicate, especially inadvertently. Before delivering your message, consider the ways in which someone else could interpret your message and do what you can to eliminate any part of your message or behavior that could lead to misinterpretations.

It’s also important to be aware of how what isn’t said still has an impact. In most instances, nonverbal behaviors (e.g., gestures, posture, and/or eye contact) or the way in which you say your message (rate of speech, volume, and tone) may convey messages you don’t intend [see Expressing Yourself and Active Listening for more].

Gender bias affects communication, even when it’s unintentional. Especially in fields where women are outnumbered, such as engineering, physical science, or executive leadership, women who communicate in ways that include hedging, qualification, or uncertainty, are likely to be viewed as weak and less competent.

These perceptions are found even if a woman’s intent is to be less confrontational, to “save face” (i.e., apologizing), or to help a team or lab mate. See Gender and Expressing Yourself for more.

Your ability to conduct research is evident from your choice to enter a STEM doctoral program. You can use the skills you use in your own research to gather useful background information for your communications.

Knowing more about departmental policies and procedures, informal norms, and decision-making processes may help you to get a sense of whom to approach and how to do it.

Some resources you can turn to are:

- School/departmental handbooks

- Websites and other online resources (Online Resources and Supports)

- Administrative assistants

One of the most important factors in reaching your communication goals is taking into account the other person’s wants, needs and limitations. For example, it might be helpful to know more about how the department chair prefers to discuss similar matters or how your instructor has handled requests for extensions in the past.

To obtain this type of information, consider asking people around you who may have experience with the person with whom you need to speak. Remember though: keep it professional, don’t gossip or be critical.

Tip: Gather enough information beforehand to be prepared. Asking someone about a policy that you could have easily found yourself with a simple search can be annoying and diminish your credibility. Before approaching others, first think to yourself: can I find this information myself? For more, see Be Resourceful.

Self-test

Annel is having difficulty with one of her labmates, and she is trying to identify a professional way of talking with him about it. Her labmate has been repeatedly using her supplies even though she has casually asked him to stop. She decides that she should have a more direct conversation with him about respecting her workspace. What should she do FIRST?

- A. Script the conversation she wants to have with her labmate

- B. Talk with her other labmates to gather useful background information

- C. Be proactive—take the first opportunity to broach the issue with her labmate

- D. Identify the goals of her message and identify how they can best be achieved

Once you feel you have identified your goals and all of the background information, you are ready to move on to planning the interaction. An effective communication plan should follow the following four guidelines:

- Plan a sequence of actions and behaviors

- Anticipate the outcomes of your actions and behaviors

- Adjust your approach as needed

- Think through how you’ll check to see if your communication goal was achieved

To illustrate how you may go about creating a plan using these four guidelines, consider the following example:

Monique wants to talk with her advisor, Dr. Hernandez, about taking the lead on an upcoming project in their lab. She is not sure how supportive Dr. Hernandez will be since she is already committed to a number of other projects. She is trying to proceed cautiously and deliberately to convince him that she is capable of handling the extra work. In order to broach the topic with him, she uses the following plan to devise her approach.

1. Plan a sequence of actions and behaviors

Begin an interaction with a clear understanding of the context in which your conversation will take place and with an outline of the points you want to make.

- Monique would like to talk to Dr. Hernandez soon. There is an upcoming departmental party where she knows she will see him; however, Monique anticipates that this may not be the best context in which to approach Dr. Hernandez about an issue that might involve a great deal of negotiation. After thinking it over, she decides it would be best to request an individual meeting with him. She also plans to send an email that includes the reason for the meeting.

- In this scenario it is important that Monique plan the email AND the interaction. Her first step should be to identify the goals of her interaction—these may be the same or different for the email and face-to-face interaction; however, it’s likely that the main goal of the email will be to request a meeting and give him an indication of her reason for requesting the meeting, while the goals of the face-to-face conversation will be to attend to the related short-term and long-term goals, the task elements and the relational elements involved.

2. Anticipate the outcomes of your actions and behaviors

While it’s possible to overplan for an interaction with someone, you can almost never predict perfectly how the other person will react. Still, you should do all that you can to consider how the conversation could go.

- Monique is hopeful that Dr. Hernandez will be supportive of proposal; however, she knows that the next year will be a busy time in their lab and he may worry that she will be overcommitted. Monique should be prepared for some pushback from Dr. Hernandez and she should have a clear argument for why she feels she can take the lead on the new project. She should also prepare for how she will handle the situation if Dr. Hernandez is entirely against the idea.

3. Adjust your approach as needed

Remaining flexible is key to communicating your message effectively.

- Monique should be willing to take ownership of her work in their lab—either by having a plan to complete it all simultaneously or by training someone to take over some of her tasks. Depending on Dr. Hernandez’s response, she should also be prepared to suggest alternatives or even change the timeline of some of the projects. While Monique’s goals and objectives should remain the same, (e.g., completing more work that could lead to publications, building her reputation as a hardworking and reliable student, and continuing to build her relationship with Dr. Hernandez) she can only take action based on the events and outcome of their meeting.

4. Think through how you’ll check to see whether your communication goal was achieved

It is important that regardless of the difficulties that arise in communicating your message, your message is still received and understood.

- If Monique’s message is clearly planned, then theoretically her overall goal of leading the new project will be enacted and she will be able to move forward in one way or another. If misunderstandings arise, Monique can use perception-checking [see Active Listening] to clear up any confusion.

Not all communication interactions allow for or even require the full amount of planning detailed in the example above. However, it’s always helpful to go into a communication interaction with an idea in mind of what you’re going to say and how you’re going to say it. Rehearsing in your head or practicing your message verbally beforehand can help prepare you for many of the possible scenarios. If you’ve taken the time to plan out and practice the specific message you want to communicate ahead of time, it will be stored in your head and easily accessible when you find yourself in the midst of the interaction.

With rapidly evolving options for communicating, like technology and social media, there are more and more ways that students can communicate with other students and professors. Although it may seem easy to send a quick email while you’re thinking about something or to drop into a professor’s office, your decision about the channel or mode of delivery can be an important one [see The Context].

When deciding between methods, consider your audience and whether electronic or face-to-face communication might be better in a given situation. Examples of important questions you may ask yourself include:

- Would it be best to give the person some time to think about my reason for contacting them?

- Would it be best to copy or include other people?

- Do you want or need a record of your communication?

All of these might be reasons to use an electronic form of communication. Conversely, when you need to hold a serious or unexpected conversation, get consent for a project, request to borrow resources, or discuss a complicated or unclear topic, it is probably better to request a face-to-face meeting.

In other situations, deciding what is/isn’t appropriate may be a little more difficult. In these situations, it becomes doubly important to consider your audience and the medium of your communication.

Examples of these kinds of situations might include:

- Is it appropriate to have a particular conversation over chat?

- Should you text a professor when he or she doesn't text you often or at all?

- Are social media sites ever appropriate for discussing work-related tasks, problems, etc.?

- Is it time-sensitive and is a text or voicemail necessary to get the answer in the timeframe that you need it?

The answers to all of these questions depend on the norms of your environment and the dynamic you have with the other person; however, it is always best to err on the side of caution:

- Don’t call or text unless it’s necessary and you have established this as the preferred method of communication

- Don’t use chat or social media to talk about work or important work-related issues

- Don’t drop-in on someone impulsively if they are busy or if it is something that would require some time to prepare an answer for.

Remember that electronic conversations (email, chat, texting, etc.) are permanent. That can be useful to you if you need to keep a record of a conversation or provide evidence of something that was said. However, it goes both ways. If we’re not careful in our messages, it can potentially have dire consequences for us.

Know your audience

Deciding on a mode of communication will be largely influenced by who is the recipient of the message. Think about whether this person is required to check email frequently as a part of the job (such as an office assistant or the director of a program) or whether or not they have explicitly or implicitly communicated their preferences regarding electronic or face-to-face communication.

Some professors rarely check their email or are slow to respond while others will only accept meeting requests after an initial email communication. Ask yourself: what do I know about the person with whom I am communicating? Then act appropriately.

Dealing with the unexpected

Despite your best efforts at structuring communication interactions in advance, there will always be times in which unexpected things arise—your professor or advisor wants to speak to you after class or a labmate catches you in the hall to make a request for your time or ask a question that requires an immediate answer.

Similarly, conflicts can arise that need quick resolution or you may need to step into a situation to mediate [see Conflict Management]. You may even need to advocate for yourself suddenly with a supervisor or advisor [see Expressing Yourself Assertively and Negotiating].

The ideal is not to hide from anyone who might communicate with you spontaneously but to see these interactions as an opportunity to impress them with your composure.

Self-test

Because of problems in your lab, you need an extension on your dissertation defense. This is the second time you’ve requested one so you are nervous about the response you may get.

- A. Convey your message at your earliest convenience. If you wait, you’ll lose the nerve to ask.

- B. Figure out how you want to convey your message, plan what you want to say, and prepare for the unexpected—both positive and negative.

- C. Go with what feels comfortable. That way you’ll be more relaxed and convey more confidence; planning it out may inhibit that.

- D. Make sure you create a script that addresses your short-term goals. Don’t worry about longer-range issues, as they will dilute your message.

Being able to communicate effectively requires time, practice, and planning. Taking time to plan out your messages before you deliver them, both written and verbal, can pay huge dividends for you in the end.

- Remember that relationships are what you depend on for the long term in your career. Even if you have a communication goal in the self or other domain, consider the relationship domain in your planning.

- Plan ahead for all of the outcomes—both positive and negative. In planning for alternate outcomes, you can create scripts to use if needed to get the conversation back on track.

- Consider the norms of your department. Your fellow grad students are an excellent source of information. If you have an interpersonal issue that needs to be resolved, once you determine your goals, ask someone to share their experiences and knowledge so you may enter the communication interaction with the necessary background information.

- Practice professional communication. Try to give others notice about meetings and let them know in advance what your questions are (after you have done your homework--see Be Resourceful). Email usually is best and preferred over other more casual forms of communication (e.g., dropping in unexpectedly, instant messaging, calls to personal phones, texting, etc.).

Bisel, R. S., Messersmith, A. S., & Kelley, K. M. (2012). Supervisor-subordinate communication: Hierarchical mum effect meets organizational learning. The Journal of Business Communication 49(2), 128-147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021943612436972

Brammer, C. (2018). Communicating as women in STEM. San Diego: Academic Press.

Dibble, J. L., Wisner, A. M., Dobbins, L., Cacal, M., Taniguchi, E., Peyton, A., van Raalte, L., & Kubulins, A. (2015). Hesitation to share bad news: By-product of verbal message planning or functional communication behavior? Communication Research, 42(2), 213–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212469401

Guntzviller, L. M., & MacGeorge, E. L. (2012). Modeling interactional influence in advice exchanges: Advice giver goals and recipient evaluations. Communication Monographs, 80(1), 83-100. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2012.739707

Lakin, J.L., & Chartrand, T.L. (2003). Using nonconscious behavioral mimicry to create affiliation and rapport. Psychological Science, 14(4), 334-339. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.14481

Leach, R. B., & Wang, T. R. (2015) Academic advisee motives for pursuing out-of-class communication with the faculty academic advisor. Communication Education, 64(3), 325-343. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2015.1038726

Maji, S., & Dixit, S. (2020). Exploring self-silencing in workplace relationships: A qualitative study of female software engineers. The Qualitative Report, 25(6), 1505-1525. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2020.4290

Palomares, N. A. (2013). When and how goals are contagious in social interaction. Human Communication Research, 39(1), 74-100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2012.01439.x

Palomares, N. A., Grasso, K. L., & Li, S. (2015). Understanding others’ goals depends on the efficiency and timing of goal pursuit. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 34(5), 564-576. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X15579913

Step, M. M., & Finucane, M. O. (2002) Interpersonal communication motives in everyday interactions. Communication Quarterly, 50(1), 93-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463370209385648

Wolfe, J., & Powell, E. (2009). Biases in interpersonal communication: How engineering students perceive gender typical speech acts in teamwork. Journal of Engineering Education 98(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2009.tb01001.x

Outlines a philosophy on time management.

Suggestions for defining research.

Proactive Approach and Adapting Environments

How to adapt experimental methods to match a lifestyle.

Is the Effort Worth the Outcome?

Explains when to confront a problem and when it may be better to maneuver around it.

The Role of the Dean in Fostering Progress at the Institutional Level

The importance of a good leader in setting standards for diversity, climate, and tenure policies.

The Importance of Having Positive Working Relationships: A Case Study

The importance of good working relationships and when it's worth putting forth effort.

The importance of being open and honest with your advisor.

Planning Experiments Around Breast Feeding, Productivity, and Encouragement (Part 1)

Creating a schedule and meeting an advisor's expectations

Communicate Effectively

Explains that satisfaction comes from working with students and the opportunity to make new disco

Explains that satisfaction comes from working with students and the opportunity to make new disco

The importance of learning from mistakes and persisting despite setbacks.

The importance of learning from your effort, regardless of the outcome.

Advice on how to seek out support in graduate school and how to bounce back from setbacks.

Shares the excitement that comes from collaborating with others to make new discoveries.

Elaborates on the standard practice of science despite cultural differences.

Strategies for negotiating as a faculty member.

When it's time to graduate and when it's important to start learning on the job.

Highlights the transition into graduate level science where the answers aren't known.

The importance of goal setting and using others' experiences to make strong choices about your own p

Advice for balancing research and fun in graduate school.

Advice for students: stay focused, ask questions, and remain open-minded when working with others.

How to adapt experimental methods to match a lifestyle.

How to negotiate a schedule for raising a family and overcoming setbacks in a new career.

The importance of giving yourself credit and remembering why you are doing what you're doing.

The importance of peer relationships and the learning process that takes place despite concrete outc

Working with graduate students is a rewarding aspect of being a faculty member.

Advice for graduate students on how to maintain their confidence, courage, and dignity.

Emphasizes peer relationships and departmental climate.

How to handle being accused of having an affair with the advisor.

Explains an interdisciplinary branch of physics and the passion for research, service, and teaching.

Teaching as the impetus for work.

Discusses necessary precautions to take as a female student working late nights on campus.

Discusses necessary precautions to take as a female student working late nights on campus.

Being accused of cheating and regrets about not being more assertive.

Being accused of cheating and regrets about not being more assertive.

The importance of self-authorship and using graduate school as a process for self-definition.

Reminder that support can be found in unexpected places.

Urges female graduate students to persist in the field of mathematics because the field needs divers

How being unaware of being the only woman was advantageous to program success.

Alternatives to departmental isolation and the importance of networking.

Environmental issues faced in academia.

The importance of first impressions in choosing a graduate program.

Satisfaction comes from interacting with intelligent people across cultures.

Adjusting physical appearance to fit in with peers.

The importance of remembering that graduate school is only one part of a larger career.

Describes an incident of receiving a lower grade than a man for similar work.

The opportunity for freedom, growth, and collaboration as a faculty member.

How to survive the aftermath of a sexual harassment incident.

Highlights the gendered assumptions encountered as a faculty member.

The Importance of Having Positive Working Relationships: A Case Study

An alternative way to approach being the only woman in a given situation.

Contributions to the field are reflected through choices.

The importance of sharing stories of sexual harassment with others to gain support.

The importance of finding the right advisor to support your research goals.

How to handle being accused of having an affair with the advisor.

Explains when to confront a problem and when it may be better to maneuver around it.

How to be upfront, direct, and assertive when confronting instances of sexual harassment.

Highlights the universal customs of science.

Class performance builds confidence to remain in program.

Captures the annoyance of male colleagues making sexist assumptions and the challenges with conferen

The importance of recognizing the progress that has been made by women in science fields.

Advice for accomplishing your academic goals without making unnecessary compromises.

Emphasizes the challenge with saying no, but the importance of learning to do so.

How to make friends with colleagues to encourage a supportive environment.

Underscores the challenges that come from being the only woman in an academic department and gives s

Highlights an experience in which peers were not only colleagues, but also friends.

How the physical space in a laboratory allowed for collaboration among colleagues.

The importance of a good leader in setting standards for diversity, climate, and tenure policies.

How to observe others' reactions to subtle comments in order to gauge an appropriate response.

Urges students not to get wrapped into issues that do not directly involve them.

Departmental reactions to the choice to have children.

How to refute sexist comments and challenge gendered assumptions.

The importance of sharing stories of sexual harassment with others and realizing that you are not al

Confronting a male colleague with contradictory findings at a conference.

How colleagues can assist in making the transition into graduate life easier by sharing information

Captures the small but noticeable annoyances that come with being the only woman.

The importance of picking your battles to avoid unfair labeling.

Reminder that it is not necessary to feel comfortable socially to do good science.

Gender stereotypes faced in getting into graduate school and conducting research.

How to seek support from administrators outside the department when dealing with departmental sexism

The first realization that being a woman in science was outside the norm.

Challenges of being international and female, particularly with regards to an academic career and th

Suggestions for how to deal with sexist comments.

Playing a variety of roles as the only woman in the department.

The process of establishing yourself in the same department as your spouse.

Emphasizes positive peer relationships within her cohort.

The challenges of working in male-dominated academic environments and the negative stereotypes assoc

The feasibility of pursuing a family and science.

The importance of hearing other people's stories.

The importance of understanding priorities and allocating resources accordingly.

Advises how to keep family informed about research goals and progression from student to faculty mem

Explains some of the setbacks in dating relationships.

Advises students to continue to pursue their education because the payoff is self-respect.

The importance of believing in yourself, admitting your mistakes, and continuing to do what you love

How to accept non-traditional relationships and lifestyles in academia.

Notes the challenges of a dual career marriage and the obstacles in fighting for tenure and balancin

The process of overcoming setbacks related to career options and personal relationships.

How to balance motherhood responsibilities in graduate school.

The importance of supportive peer relationships.

Being married in graduate school and having children as a faculty member.

Advisor's experiences encourage well-informed career decisions.

The importance of a supportive network of colleagues.

Doing something useful to make a difference and how to appreciate a happy, supportive work environme

Taking time off before pursuing her PhD.

How a supportive department and a modified teaching schedule allowed for maternity leave.

How to sustain taking time off and pursuing the PhD later in life.

Advises how to keep family informed about research goals and progression from student to faculty mem

The importance of a supportive extended family in helping to balance school and children.

The importance of having a number of things in your life that bring you joy and satisfaction.

Understanding your strengths and weaknesses, but ultimately giving yourself recognition for your suc

The importance of learning over time and remaining positive in the face of criticism.

Motivation for doing work: interacting with students and doing research that can make a difference i

Emphasizes the challenge with saying no, but the importance of learning to do so.

The importance of remaining passionate and remembering that the PhD opens doors.

The importance of defining clear goals, remaining self-confident, and learning to say no.

The importance of allowing yourself the opportunity to change your mind and reconsider your goals.

The importance of knowing what you want and expecting tradeoffs on the path to get it.

Making discoveries and collaborating with others brings satisfaction.

Creating a schedule and meeting an advisor's expectations.

Advises graduate students to take a semester off if they choose to have a child because it is too ch

Explains the role children play in career choices.

Using leisure activities to relieve stress and build friendships.

The satisfaction that comes from working with colleagues and interacting with others.

The decision to get married in graduate school.

The importance of maintaining a balanced lifestyle to alleviate stress.

Addresses personal relationship sacrifices.

The importance of nurturing relationships outside of academia.

Explains the choice to have children in graduate school.

Challenges with being married to a fellow academician and finding faculty positions.

How a flexible schedule as a professor made it possible to have a family and a career.

The importance of evaluating your priorities to create balance and happiness.

Appreciation for advisor's assistance in transitioning to the US.

Emphasizes the joy in working with others and giving back to society.

Chronicles the evolution of a career over time.

Suggestions for how to increase women's participation in science with an emphasis on policy change.

The importance of being open and honest with your advisor.

How a positive advisor challenged his students to think for themselves.

Highlights the obstacles faced when trying to have research reviewed by the advisor and emphasizes t

The importance of having a variety of mentors throughout your graduate experience.

Challenges faced with establishing yourself as an independent researcher separate from an influentia

The importance of asking questions and searching for creative solutions to new problems.

The importance of finding a good advisor and making sure to get everything in writing.

Challenges in confronting the advisor with news of pregnancy.

Experiences with an international advisor.

How to maintain good relationships with colleagues while being motivated to finish the program qu

The importance of giving back to students and making an impact in their future education and care

An Arizona State University project, supported by the National Science Foundation under grants 0634519, 0910384 and 1761278

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. © 2021 CareerWISE. All rights reserved. Privacy | Legal

Comments

We want to hear from you. Did this page remind you of any experiences you’ve had? Did you realize something new? Please take a moment to tell us about it—and we’ll keep it confidential.