Communicate More Effectively

Career Wise Menu

Learn Communication Skills: Communicate Assertively

- Learn to distinguish between assertive and other types of communication

- Learn to avoid common problems associated with ineffective communication styles.

- Learn to use assertive techniques in your interactions with others.

- Learn to set appropriate boundaries and limits.

- Learn to understand and navigate situations in which gender can be a barrier to assertiveness.

“Equality in human relationships, enabling us to act in our own best interests, to stand up for ourselves without undue anxiety, to express honest feelings (choices, needs or opinions) comfortably, to exercise personal rights (and setting limits to the behavior of others) without denying the rights of others,” nor hurting, intimidating, manipulating, or controlling them -- Alberti & Emmons, 2017

What a week! My advisor asked me to stay after hours three different times to do various tasks on our project. And then Miguel asked me to review his paper; and I did, even though my paper is also due on Friday. And why am I the only one who ever fills the copier with paper—Peter said it was broken and had me “fix” it by putting in a new ream. Ugh!

This might be an example of a difficult week or reflective of a rough spot into which this student has fallen. She can’t seem to say “no”. You may have found yourself in similar situations. When people encounter these kinds of difficult or uncomfortable moments, and/or they notice negative patterns affecting their work, they tend to react in one of the following ways.

- Do nothing (avoid the issue)

- Play the victim (blame someone else)

- Get their way no matter what (act aggressively)

- Be sensitive to others but stand up for themselves (act assertively)

While they can choose to do any of the above, an assertive response (option 4) will likely produce the most positive outcomes. Assertiveness is a style of communication that focuses on advocating for yourself. Different from aggression, being assertive means standing up for and communicating what you want in a clear fashion, while respecting your rights and feelings along with the rights and feelings of others. People who act assertively:

- Are active in their environment and make things happen

- Express their thoughts, feelings and needs

- Communicate with others in an honest and direct way

- Show self-respect by acknowledging their shortcomings but not beating themselves up

Acting assertively will empower you in your interactions, both personally and professionally. It can lower your stress and enhance your coping strategies. In fact, women who are more assertive generally feel they have more control over important tasks and are more able to take on challenges. This module will help you recognize assertiveness, and learn some approaches for being assertive in your own interactions with others.

Assertiveness Self-Check

To get an idea of your level of assertiveness, ask yourself the following questions:

- Do you feel imposed upon/taken advantage of, or ignored in your exchanges with colleagues?

- Are you unable to speak your mind and ask for what you want?

- Do you find it difficult to stand up for yourself in a discussion?

- Are you inordinately grateful when someone seeks your opinion and takes it into account?

If you answer ‘yes’ to most of these questions, you may need to consider becoming more assertive. While it can feel more “natural” to certain people, being assertive takes practice like any other skill. If you find that it is difficult for you to be assertive, keep in mind that anyone can learn these skills and behaviors—they’re not inherent to any one personality or type of individual.

NOT asserting yourself in the academic environment brings drawbacks. By not being assertive, you may miss out on funding or fellowships, or even being considered for such opportunities. By not speaking out when you are treated unfairly, you can implicitly condone the status quo or even reinforce biased stereotypes. Being non-assertive in the classroom can also affect how your professors view your work. In fact, studies have shown that professors sometimes feel like they have to “spoon feed” materials to students if students don’t take an active role in their work. The “bottom line” is that if you are communicating openly, being clear about your needs, expressing your concerns, and taking initiative—all in a timely manner—you will be more successful in your academic and professional endeavors.

Self-test

Since having the baby, I’ve been so busy and it’s taking me more time to get my assignments completed than it did before. Again, I’m going to need an extension on a paper because my baby was sick all week. I should…

- A. Let my professor know that I have a new baby and I’m really overwhelmed.

- B. Be clear with my professor about my situation this week and directly ask for that extra 3 days I’ll need to complete the assignment.

- C. Just turn it in as soon as I can finish it—maybe I’ll turn in whatever I have ready by the due date and not worry about the grade.

- D. Think about dropping the class because this situation is bound to happen again and it’s just so stressful.

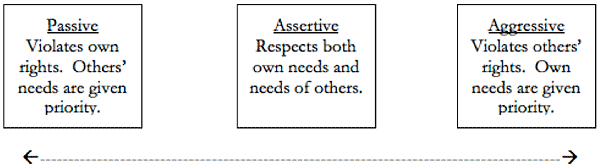

Assertiveness is an interpersonal communication technique that we can employ when we need to obtain a particular goal or objective. When we are assertive, we are able to express ourselves in a way that doesn’t violate the rights or needs of others, while advocating for our own wants and needs. Assertive communication is different from aggressive or passive communication. Aggressive communication violates the rights of others in favor of oneself, while passive communication disregards one’s own rights in favor of others.

By becoming aware of the characteristics of these styles, you can begin to see the things you need and want to change in order to become more assertive. Table 1 shows different aspects of these approaches, and examples of what they might look like.

Table 1: Passive, Assertive & Aggressive Approaches to Communication

| Type of Communication | Passive | Assertive | Aggressive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose | To Avoid Conflict and/or always be agreeable | To communicate honestly and directly in order to achieve your needs and goals | To always get what you want - to win! |

| Characteristics |

|

|

|

|

Possible Returns |

|

|

|

| Examples | "I was heading to another appointment, but I guess it's not that important and I could postpone it until later in the week to help you" | "I realize that you need help with this project. I have another appointment now, but I could help you during my office hours later in the week" | "You always approach me at the last minute and expect me to drop everything to help you, but you never help me when I need help. So, no, I will not help you now" |

Assertive expressions and how they are perceived are often a function of gender. Women are significantly less likely than men to use assertive speech in mixed-gender interactions (Leaper & Ayres, 2007). Women are also far less likely than men to initiate negotiations, especially in situations where the appropriateness of negotiation is unclear (Kugler et al., 2018). Not acting assertively in these situations can lead to significant consequences—less pay, fewer opportunities, or even getting passed over for awards, honors, or promotions [see Negotiating for more].

Lower levels of assertiveness in women can be tied to socialization. Society expects women to be passive, non-confrontational, interdependent, accommodating, and nurturing. Remember that these are just expectations—they are not how it has to be. However, because expressing yourself assertively as a woman can go against some of these societal expectations, it is important to be prepared for others’ reactions, so that you can deal with them effectively.

In most cultures, characteristics of assertiveness and leadership are associated with men and masculinity, while women are thought to be more communal, unselfish, and care-taking (Rudman & Glick, 2001) . This mismatch between qualities attributed to women and qualities necessary for assertiveness and leadership subjects women to a double standard. Women from different cultural backgrounds may feel even more uncomfortable by these kinds of norms.

Conversely, women in leadership positions can be thought of as too aggressive or not aggressive enough, and what appears to be assertive in men often looks confrontational, or self-promoting in women. A penalty for women whose communication is perceived as too dominating is being disliked (Rudman et al., 2012; Tiedens, 2016). When women who are performing traditionally male roles are seen as doing something that conforms to feminine stereotypes, they are judged as too soft, too emotional, and too unassertive. This double standard may make it difficult to stand up for yourself, or discourage you from acting assertively altogether. However, if you choose not to assert yourself, you can be viewed as passive, or even worse—that you agree with or accept whatever situation may be troubling you!

Women are more likely than men to use tentative language, i.e., expressions of uncertainty, qualifiers, hedges, tag questions, and intensifiers (Lakoff, 1973; Leaper & Robnett, 2011). Modifying wording to be more consistent with gendered expectations is so common that many women are not fully aware of doing so. Using these language forms can also be interpreted as a demonstration of interpersonal sensibility. It is important to recognize, however, that these types of expression are described by scholars as “powerless language”, that can by extension be problematic in environments where more masculine forms of communication prevail.

Table 2: Exercises

| If you tend to be... | Try... |

|---|---|

| Soft spoken | Raising your volume. |

| Apologetic | Getting to the point and not apologizing. |

| Wordy and give too much explanation | Stating your point in one or two short sentences. |

| Hesitant before speaking | Being sure about what you have to say. |

| Last to speak | Volunteering to share your ideas first. |

| Overly forgiving | Holding someone accountable by explaining your views without saying, "That's ok." |

| Agreeable | Finding constructive criticism to offer new perspective. |

While gender presents some unique challenges to being assertive, you can overcome these challenges by maintaining awareness, practicing your skill set, and being consistent in your assertions. Here are a few suggestions for women who are navigating being assertive in a traditionally male-dominated environment [see Expressing Yourself for more]:

- Don’t rush in. Use assertion selectively and thoughtfully. Ease in, but don’t let yourself be taken advantage of—it’s not necessary to be assertive all the time, but it is important to establish that precedent.

- Watch your thoughts. To stay assertive, get into the mindset of thinking assertively. Learn to recognize your negative self-statements, and replace them with affirmations and confident language.

- Project a positive image. Visualize how you would like to be—form a mental image of an assertive you, then make that image as real as possible.

- Be confident but sensitive in the way you express yourself. Watch out for verbal and nonverbal expressions that convey lack of confidence [see Expressing Yourself]. Use positive body language and Active Listening skills to help put others at ease.

- Recognize communication styles in others, and respond appropriately. If you are dealing with a passive person, then rather than let them be silent, encourage them to contribute. When dealing with an aggressive communicator, prevent the situation from getting out of hand by adopting one of the tactics above, like “Let me think about it first,” giving you time to gather your thoughts, and affording them time to calm down.

As you are preparing to be more assertive with others, keep the following in mind:

- Remember that assertiveness is a skill set that takes practice. It may be necessary to practice the techniques and guidelines in some neutral situations in which you won’t be too emotionally charged. As you gain proficiency, you can start applying them in more difficult situations.

- Watch your nonverbals (see Expressing Yourself). It is possible to use assertive techniques in an aggressive or passive way if you are not careful with your nonverbal communication. Remember to keep your voice calm, maintain eye contact, and keep a relaxed and confident body posture.

- Recognize that choosing to be assertive in a situation is a strategy rather than a style (Pfafman & McEwan, 2014). Similarly, choosing not to be assertive in a situation can be a deliberate strategy that helps you meet your objectives in a particular context.

“I” messages are an effective way to express your standpoints in difficult situations. “I” statements help you take responsibility for your part of the issue—your feelings and your perception of the problem and how it affects you—while effectively addressing the behavior of the other person in the situation. Using “I” creates a dialogue where you are stating your own feelings and thoughts and can’t be so easily dismissed or refuted.

When using “I” messages, keep the focus on yourself and how you feel, given the other person’s behavior. If you initially frame the concern with pronouns and phrases like “you”—“you really frustrate me when you forget our deadlines and make our projects late,” you’re suggesting the other person is to blame, which may put them on the defensive. A more productive way of asserting your feelings might be to say, “I feel frustrated when our projects get turned in late. I want to work together better to meet our deadlines because I feel like I’m doing what I can to get them in on time.” Using “us” and “we” statements helps propose arrangements that can satisfy both parties without damaging the relationship.

See how “I messages” are used in the table below, which outlines six techniques for acting assertively.

Table 3: Assertion Techniques

| Technique | Definition/Purpose | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Assertion |

|

|

| Empathetic Assertion |

|

|

| Discrepancy Assertion |

|

|

| Negative Feelings Assertion |

|

|

| Responsive Assertion |

|

|

| Consequence Assertion |

|

|

Remember, trying out new styles of communication can demonstrate your adaptability and flexibility, but be aware that others may be unsure about how to respond to you at first. Others may be surprised initially and you may be surprised by how others respond to you (See Receiving and Responding to Feedback). Be confident about your self-experimentation and be prepared to troubleshoot afterwards.

When you choose to assert yourself, be sure you know the reason(s) behind your decision. If you are clear about your reasons, you will be less likely to get angry or emotional. Make sure your priority when asserting yourself is to express your personal limits, clarify something important, and/or create positive change, because our assertiveness affects our outcomes.

An important part of expressing your limits is “calling out” others when they engage in a behavior that you find to be inappropriate or offensive. How many times has one of your labmates offended female colleagues, without necessarily recognizing it? Calling out the person in this situation is important, but it may not be easy. Research has shown that when women experience sexism, they are more likely to confront the person who committed the inappropriate behavior when they know that doing so will make a difference, and when they also know that the risks of doing so are low. This may describe how you have felt when similar situations have happened to you. However, keep in mind that calling out the other person does you both a favor. You may not be able to change their attitude or behaviors permanently, but you can place limits and expectations on your shared space, and maybe spare your colleague a few dirty looks from others. For more on this topic, see the Recognizing Sexism and Microaggressions modules.

Being assertive also entails standing up for yourself when necessary. Have you ever found yourself in a situation where you think your labmates, class, or group are taking advantage of you? If you do not act assertively in these situations, you run the risk of communicating to others that you are okay with what’s going on, or that you even agree! Remember: others may not know that something is a problem for you or bothers you unless you tell them.

In some cases, it’s up to you to express what is and is not acceptable to you. Table 4 illustrates some examples of how you can use assertiveness to do so, and the effect it has on you and others.

Table 4: Applying Assertiveness to Establish Boundaries

| Situation | What to Say | What it does |

|---|---|---|

| Two of your labmates continually tell inappropriate jokes about immigrant workers. | "I see that Max and Fernando find all of your immigration jokes funny, but they kind of offend me. So, maybe you can amuse yourself with those things but don't express it." | Clearly shows where you stand and presents a direct opinion to avoid future offensive situations |

| You are working on a group project for a class. The group wants to meet over the weekend, but you already have an engagement, and they assume you will be ok with the decision. | "I understand that you think this weekend is the best time for us to work on the project, but I have another commitment for Saturday. How about we pick up where we left off on Sunday evening?" | Shows empathy for the other person's position and offers an alternate solution. |

| Your labmates consistently leave equipment out and/or fail to clean up after themselves, leaving you to take care of the mess. | "When I came in this morning, all the beakers were in the sink. It's not a magician that miraculously cleaned them up - it's me! I think we should come up with some kind of system so we can share these responsibilities." | Utilizes subtle humor but brings awareness to the situation and presents a solution-focused objective. |

Self-test

Many students come late to the class for which you are a teaching assistant. The number of students who arrive after class starts varies from day to day, but it bothers you each time it happens. What would you do?

- A. If and when it happens, I’d mention that it’s important to arrive on time.

- B. Let it slide. I have the other students to worry about and calling it out would just be disruptive for everyone.

- C. Tell my students what the expectation is for arriving on time, put it in writing, give incentives for making it on time and tangible consequences for being late.

- D. Let the students know how inappropriate their behavior is and levy whatever consequence seems appropriate to me at the time, depending on what we have going on that day.

One of the most difficult challenges people face in becoming more assertive is learning to say “no.” However, saying “no” is one of the most effective and clear ways to set a limit on what you will or will not do, as well as on what behaviors and terms you find unacceptable. Often people don’t know their own limits—so they don’t know when to say “no.” Moreover, many people have difficulty saying “no” because they are afraid that doing so will lead to adverse consequences or missed opportunities. They may even feel like they can or should say “yes” to everything. If you fail to establish limits by saying “no” when appropriate, you may end up with too much on your plate—leaving you to feel over-extended, under-appreciated, or unfairly treated.

When to say “no”

Knowing when to say no can be a difficult task, but it is essential. One way to determine whether it is okay to say no is to ask yourself the following questions:

1. Does it benefit my interests to say no?

- Example: Your labmates want you to help write an article near the end of the semester, but you are concerned about the amount of time it will take and how it will affect your schoolwork.

- Possible Answer: If I say no to writing this article, then I’ll have more time to spend on my schoolwork.

2. Does my saying no negatively affect the well-being of someone else?

- Example: Your advisor wants you to go to a conference to help her present over the break, but you have other long-standing plans.

- Possible Answer: By not going to this conference, my advisor will have to present alone. But she’ll be okay, and will probably ask another student to help.

3. Do I have the power to say no?

- Example: You have been approved to take a leave of absence next semester, but one of your professors is pushing heavily for you to work on his grant.

- Possible Answer: I have chosen to take a leave of absence next semester so I’ll have to tell Dr. Avedes that I won’t be able to work on his grant.

4. Do I have the right to say no?

- Example: Your dissertation proposal is taking up too much time for you to finish some writing projects.

- Possible Answer: I can’t graduate without finishing my dissertation, so just because writing my proposal is taking up too much of my time I can’t really say I just don’t want to do it.

How to say “no”

Learning how to say no firmly yet gracefully is an essential skill. The first thing to do is to avoid saying “yes” on the spot. It always helps to reflect first, especially when you feel uncomfortable as soon as the request is made. The following tables offer guidelines on how to say “no” both to things people say or do (behaviors) and requests or scenarios (situations) that go beyond your limits of what is acceptable:

Table 5: How to say "no" to BEHAVIORS

| What to say | What it does |

|---|---|

| "Stop" or "No way" | If something is absolutely not appropriate, like an inappropriate or offensive remark, use the clearest language possible with corresponding physical cues. Don't say, "stop" and then laugh. Direct eye contact says you're serious. |

| "This isn't working for me" or "That's not okay with me" | Clearly lets someone know that you feel they've gone too far. Knowing where these "lines are drawn is important in setting clear social and professional expectations. |

| "That's enough" or "That's not appropriate" | Expresses your limits and what is acceptable behavior. |

Table 6: How to say "no" to SITUATIONS

| What to say | What it does |

|---|---|

| "I'd rather not commit to something if I won't be able to do a good job now. | This lets the other person know that you're keeping their best interests in mind, as well as your own personal needs. |

| "I can't right now." |

Delays/defers the task but leaves the door open to future opportunities. |

| "I have plans this evening, but thank you for asking." | Show's you're already committed but appears gracious. |

| "That sounds like a great opportunity. I'm sorry I won't be able to take you up on it." | Affirms that they have presented something worthwhile, but sets your limits. |

Remember that it is within your right to be able to say no, and that doing so is perfectly reasonable. Don’t feel like you have to explain yourself too much—you are entitled to say no, especially if you have thought about why you are saying it. Being simple and concise can convey confidence; giving a lengthy, nervous explanation of why you just said no can lead to further confusion.

Again, remember that assertiveness is a skill set that takes practice. The following are 10 guidelines to follow as you use assertiveness in your interactions with others.

- Know what you will and will not put up with. You don’t want to be overly vigilant or extremely passive. There’s a comfortable and appropriate middle ground, one that only you can define for yourself. You also have the right to say “no” and not feel like a terrible person.

- Just say NO. Somehow “no” has become a foul word, a reflection of inability, or an indication that you’re not committed. Change how you think about “no.” Refer to the prior section on “how to say no” for tips on handling the situation tactfully. Your saying “no” and letting them know where you stand also helps other people work for the collective good more effectively.

- Focus on RIGHT NOW. Regardless of your personal style, culture, or upbringing, it’s important to learn some skills and make appropriate adjustments that suit how things are for you NOW. Don’t let yourself be distracted by ‘forever,’ or even by ‘later’ when you go home to your roommate or companion—instead focus on the academic environment where you find yourself at this moment. It’s like a skill set you may have for the lab: you must clean and sterilize your equipment—that’s common practice for experiments. However, you wouldn’t have the same standards for your dishes at home. The same goes for your attitude and awareness in the academic environment. You may have to do things that you may ordinarily find uncomfortable, but they work in this context.

- Difficult, yes, impossible, no. Don’t make a bad situation worse. Even though you may face difficult situations all the time, focusing on the negative aspects of these situations can make them seem much more difficult than they really are. There is a big distinction between an untenable situation and an issue that is merely uncomfortable or irritating.

- A little good humor goes a long way. Practice your responses. Often humor or poignant one-liners can drive home a point without making it a drawn-out discussion or serious issue. Perhaps you’ve had a deer-in-the-headlights reaction when a colleague made a rude comment. After being silent, you may have reviewed the situation in your head, wishing you had done something differently. Since inappropriate comments are unfortunately quite prevalent in certain environments, you may have another (if not many) opportunities to address these types of behaviors.

- What will happen if…? Remember not to make assumptions. An important question to ask yourself is “What will happen if I ask?” or “What will happen if we talk about this situation?” Will the world come to an end? Probably not. Even if you say the wrong thing, or don’t get the result you were hoping for, you can always do something different next time.

- Careful listening. When discussing difficult issues, remember to listen. Listening is an active process, where you are paying attention and considering what the other person is saying [see Active Listening]. While you may be tempted to defend yourself or make an important clarification; there will be a time when you can do that. If you are not listening, you may be reading things into a situation that are not really intended.

- Being active. You don’t have to assert yourself only because an uncomfortable situation has arisen. Learning to define your needs is a good step towards meeting your personal and professional goals. You can use your assertiveness skills to take initiative in your workplace by expressing your ability to take on leadership responsibilities. You can do the same in the school environment by sharing your thoughts on the material/information being discussed.

- The Chinese Bamboo Tree. After careful preparation of the soil, this plant grows only underground for its first four years of life. Then in its fifth year, it can grow up to eighty feet! This is a metaphor for the importance of gaining strength and empowerment from the inside out. The underground lifespan of the bamboo tree is an example of how you may not see immediate results to your planning, preparation, and work. However, you are indeed growing and gaining strength. At the right time with the right skills and effort, things will change.

- It’s all about you. Understand and take responsibility for the fact that you, and only you, create your perspectives and feelings. These perspectives and feelings create your reality. This is a lot of responsibility but also gives you a great deal of control. When people feel powerless or think that a situation is outside of their control, it allows them to put the blame or accountability elsewhere. Keep things in perspective and know that regardless of the other person’s response, you’ve done your best to address the situation.

As a woman in a science, technology, engineering, or math field, you are outnumbered. Being in the minority means that there will be inequities that affect you. However, it won’t always be this way, and by being assertive now, you can empower yourself but also other women in your field. Asserting yourself as a professional woman can help eradicate unhelpful gender stereotypes and pave the way for others to come.

- Try journaling the situations in which you find it difficult to be assertive—write down the people who were there, your thoughts and behaviors, and other things that may have been obstacles. You’ll be more aware next time and you’ll be able to track your progress.

- If you struggle with being assertive, remember that as you become more assertive it will be a change in your interpersonal style to which others may not be accustomed. They may meet it with resistance at first. Stay with it!

- When others are being persistent in their requests and you feel it a violation of your rights to comply, stay calm and let yourself be a “broken record”—remain firm in your assertions and they’ll eventually get it.

Alberti, R., & Emmons, M. (2017). Your perfect right: Assertiveness and equality in your life and relationships (10th ed.). CA: Impact.

Ames, D., Lee, A., & Wazlawek, A. (2017). Interpersonal assertiveness: Inside the balancing act. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 11(6), e12317–n/a. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12317

Good, J. J., Moss-Racusin, C. A., & Sanchez, D. T. (2012). When do we confront? Perceptions of costs and benefits predict confronting discrimination on behalf of the self and others. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 36(2), 210-226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684312440958

Kugler, K. G., Reif, J. A. M., Kaschner, T., & Brodbeck, F. C. (2018). Gender differences in the initiation of negotiations: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 144(2), 198–222. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000135

Leaper, C, & Ayres, M. M. (2007). A meta-analytic review of gender variations in adults’ language use: Talkativeness, affiliative speech, and assertive speech. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 11(4), 328-363. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868307302221

Leaper C & Robnett R. D. (2011). Women are more likely than men to use tentative language, aren’t they? A meta-analysis testing for gender differences and moderators. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35(1), 129-142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684310392728

Pfafman, T. M. , & McEwan, B. (2014). Polite women at work: Negotiating professional identity through strategic assertiveness. Women's Studies in Communication, 37(2), 202–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2014.911231

Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (2001). Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 743–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00239

Rudman, L. A., Moss-Racusin, C. A., Glick, P., & Phelan, J. E. (2012). Reactions to vanguards: Advances in backlash theory. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 45, pp. 167-227). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00239

Ury, W. (2007). The power of a positive no: How to say no and still get to a yes. New York, NY: Bantam Dell.

Williams, M. J. , & Tiedens, L. A. (2016). The subtle suspension of backlash: A meta-analysis of penalties for women's implicit and explicit dominance behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 142(2), 165–197. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000039

The pros and cons of being the only woman in a department and the importance of setting boundaries and knowing your own limitations.

On Speaking Up: A Conference Experience

Confronting a male colleague with contradictory findings at a conference.

I Have Not Figured Out How to Say "No"

Emphasizes the challenge with saying no, but the importance of learning to do so.

Suggestions for defining research.

How a positive advisor challenged his students to think for themselves.

Highlights the obstacles faced when trying to have research reviewed by the advisor and emphasizes the steps necessary to make adequate progress in the program.

The importance of being open and honest with your advisor.

Dealing with Assumptions and Accusations (Short Version)

Being accused of cheating and regrets about not being more assertive.

Communicate Effectively

“Some people think that you have to be the loudest voice in the room to make a difference. That is just not true. Often, the best thing we can do is turn down the volume. When the sound is quieter, you can actually hear what someone else is saying. And that can make a world of difference.”

Explains that satisfaction comes from working with students and the opportunity to make new disco

Explains that satisfaction comes from working with students and the opportunity to make new disco

The importance of learning from mistakes and persisting despite setbacks.

The importance of learning from your effort, regardless of the outcome.

Advice on how to seek out support in graduate school and how to bounce back from setbacks.

Shares the excitement that comes from collaborating with others to make new discoveries.

Elaborates on the standard practice of science despite cultural differences.

Strategies for negotiating as a faculty member.

When it's time to graduate and when it's important to start learning on the job.

Highlights the transition into graduate level science where the answers aren't known.

The importance of goal setting and using others' experiences to make strong choices about your own p

Advice for balancing research and fun in graduate school.

Advice for students: stay focused, ask questions, and remain open-minded when working with others.

How to adapt experimental methods to match a lifestyle.

How to negotiate a schedule for raising a family and overcoming setbacks in a new career.

The importance of giving yourself credit and remembering why you are doing what you're doing.

The importance of peer relationships and the learning process that takes place despite concrete outc

Working with graduate students is a rewarding aspect of being a faculty member.

Advice for graduate students on how to maintain their confidence, courage, and dignity.

Emphasizes peer relationships and departmental climate.

How to handle being accused of having an affair with the advisor.

Explains an interdisciplinary branch of physics and the passion for research, service, and teaching.

Teaching as the impetus for work.

Discusses necessary precautions to take as a female student working late nights on campus.

Discusses necessary precautions to take as a female student working late nights on campus.

Being accused of cheating and regrets about not being more assertive.

Being accused of cheating and regrets about not being more assertive.

The importance of self-authorship and using graduate school as a process for self-definition.

Reminder that support can be found in unexpected places.

Urges female graduate students to persist in the field of mathematics because the field needs divers

How being unaware of being the only woman was advantageous to program success.

Alternatives to departmental isolation and the importance of networking.

Environmental issues faced in academia.

The importance of first impressions in choosing a graduate program.

Satisfaction comes from interacting with intelligent people across cultures.

Adjusting physical appearance to fit in with peers.

The importance of remembering that graduate school is only one part of a larger career.

Describes an incident of receiving a lower grade than a man for similar work.

The opportunity for freedom, growth, and collaboration as a faculty member.

How to survive the aftermath of a sexual harassment incident.

Highlights the gendered assumptions encountered as a faculty member.

The Importance of Having Positive Working Relationships: A Case Study

An alternative way to approach being the only woman in a given situation.

Contributions to the field are reflected through choices.

The importance of sharing stories of sexual harassment with others to gain support.

The importance of finding the right advisor to support your research goals.

How to handle being accused of having an affair with the advisor.

Explains when to confront a problem and when it may be better to maneuver around it.

How to be upfront, direct, and assertive when confronting instances of sexual harassment.

Highlights the universal customs of science.

Class performance builds confidence to remain in program.

Captures the annoyance of male colleagues making sexist assumptions and the challenges with conferen

The importance of recognizing the progress that has been made by women in science fields.

Advice for accomplishing your academic goals without making unnecessary compromises.

Emphasizes the challenge with saying no, but the importance of learning to do so.

How to make friends with colleagues to encourage a supportive environment.

Underscores the challenges that come from being the only woman in an academic department and gives s

Highlights an experience in which peers were not only colleagues, but also friends.

How the physical space in a laboratory allowed for collaboration among colleagues.

The importance of a good leader in setting standards for diversity, climate, and tenure policies.

How to observe others' reactions to subtle comments in order to gauge an appropriate response.

Urges students not to get wrapped into issues that do not directly involve them.

Departmental reactions to the choice to have children.

How to refute sexist comments and challenge gendered assumptions.

The importance of sharing stories of sexual harassment with others and realizing that you are not al

Confronting a male colleague with contradictory findings at a conference.

How colleagues can assist in making the transition into graduate life easier by sharing information

Captures the small but noticeable annoyances that come with being the only woman.

The importance of picking your battles to avoid unfair labeling.

Reminder that it is not necessary to feel comfortable socially to do good science.

Gender stereotypes faced in getting into graduate school and conducting research.

How to seek support from administrators outside the department when dealing with departmental sexism

The first realization that being a woman in science was outside the norm.

Challenges of being international and female, particularly with regards to an academic career and th

Suggestions for how to deal with sexist comments.

Playing a variety of roles as the only woman in the department.

The process of establishing yourself in the same department as your spouse.

Emphasizes positive peer relationships within her cohort.

The challenges of working in male-dominated academic environments and the negative stereotypes assoc

The feasibility of pursuing a family and science.

The importance of hearing other people's stories.

The importance of understanding priorities and allocating resources accordingly.

Advises how to keep family informed about research goals and progression from student to faculty mem

Explains some of the setbacks in dating relationships.

Advises students to continue to pursue their education because the payoff is self-respect.

The importance of believing in yourself, admitting your mistakes, and continuing to do what you love

How to accept non-traditional relationships and lifestyles in academia.

Notes the challenges of a dual career marriage and the obstacles in fighting for tenure and balancin

The process of overcoming setbacks related to career options and personal relationships.

How to balance motherhood responsibilities in graduate school.

The importance of supportive peer relationships.

Being married in graduate school and having children as a faculty member.

Advisor's experiences encourage well-informed career decisions.

The importance of a supportive network of colleagues.

Doing something useful to make a difference and how to appreciate a happy, supportive work environme

Taking time off before pursuing her PhD.

How a supportive department and a modified teaching schedule allowed for maternity leave.

How to sustain taking time off and pursuing the PhD later in life.

Advises how to keep family informed about research goals and progression from student to faculty mem

The importance of a supportive extended family in helping to balance school and children.

The importance of having a number of things in your life that bring you joy and satisfaction.

Understanding your strengths and weaknesses, but ultimately giving yourself recognition for your suc

The importance of learning over time and remaining positive in the face of criticism.

Motivation for doing work: interacting with students and doing research that can make a difference i

Emphasizes the challenge with saying no, but the importance of learning to do so.

The importance of remaining passionate and remembering that the PhD opens doors.

The importance of defining clear goals, remaining self-confident, and learning to say no.

The importance of allowing yourself the opportunity to change your mind and reconsider your goals.

The importance of knowing what you want and expecting tradeoffs on the path to get it.

Making discoveries and collaborating with others brings satisfaction.

Creating a schedule and meeting an advisor's expectations.

Advises graduate students to take a semester off if they choose to have a child because it is too ch

Explains the role children play in career choices.

Using leisure activities to relieve stress and build friendships.

The satisfaction that comes from working with colleagues and interacting with others.

The decision to get married in graduate school.

The importance of maintaining a balanced lifestyle to alleviate stress.

Addresses personal relationship sacrifices.

The importance of nurturing relationships outside of academia.

Explains the choice to have children in graduate school.

Challenges with being married to a fellow academician and finding faculty positions.

How a flexible schedule as a professor made it possible to have a family and a career.

The importance of evaluating your priorities to create balance and happiness.

Appreciation for advisor's assistance in transitioning to the US.

Emphasizes the joy in working with others and giving back to society.

Chronicles the evolution of a career over time.

Suggestions for how to increase women's participation in science with an emphasis on policy change.

The importance of being open and honest with your advisor.

How a positive advisor challenged his students to think for themselves.

Highlights the obstacles faced when trying to have research reviewed by the advisor and emphasizes t

The importance of having a variety of mentors throughout your graduate experience.

Challenges faced with establishing yourself as an independent researcher separate from an influentia

The importance of asking questions and searching for creative solutions to new problems.

The importance of finding a good advisor and making sure to get everything in writing.

Challenges in confronting the advisor with news of pregnancy.

Experiences with an international advisor.

How to maintain good relationships with colleagues while being motivated to finish the program qu

The importance of giving back to students and making an impact in their future education and care

An Arizona State University project, supported by the National Science Foundation under grants 0634519, 0910384 and 1761278

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. © 2021 CareerWISE. All rights reserved. Privacy | Legal

Comments

We want to hear from you. Did this page remind you of any experiences you’ve had? Did you realize something new? Please take a moment to tell us about it—and we’ll keep it confidential.