Communicate More Effectively

Career Wise Menu

Learn Communication Skills: Receive and Respond to Feedback

- Learn to be more receptive when getting feedback.

- Learn to recognize the role of choice when interpreting feedback as positive or negative.

- Learn to identify the benefits of feedback.

- Learn to employ helpful reframing statements against self-defeating thoughts.

- Learn tools for deciding whether feedback fits you or not.

- Learn to increase awareness about how your responses to feedback may be perceived by others.

“All I ever get from my advisor is criticism. He never has anything positive to say.”

“I love the post-doc in our lab. She is very kind even when she finds something that needs to be done differently.”

Receiving and responding to evaluative information from others are essential components of our daily lives. Even if you don’t solicit feedback, others share their impressions of how you perform, act, look and carry yourself– and you react internally and externally.

As a graduate student, you may rely on feedback about your work to make progress and strengthen your skills. In fact, graduate students who get more and timely feedback from their research advisors tend to be more satisfied with their program. Even so, because of its evaluative nature and especially if it’s from someone with more power than you, feedback often evokes emotional responses.

Every piece of feedback is laden with multiple types of information. Not only do you learn about the content of what is said, but you also may learn something about the person giving the feedback from the way they deliver it.

You also learn about yourself. Feedback helps us increase awareness of our “blind spots,” or the aspects of ourselves that we cannot see objectively. Even critical feedback can bring benefits. How you choose to receive and respond to it may have an impact on the eventual outcome of your communication and maybe even your relationship.

There is no one right or wrong way to receive feedback. However, if your goal is to have a good working relationship with a colleague or supervisor, hearing them out when they give you feedback will probably lead to a better outcome than arguing or shutting down. Whenever you find yourself having a reaction to feedback, remind yourself of some of the potential benefits of receiving that new information.

| Tip: Think of feedback as something you can choose to ingest or reject. When receiving feedback, take it all in at first and chew on it to see whether it suits you. If you decide that it fits, you can choose to swallow. If not, remember you always have the choice to spit it out. |

Be receptive: be willing to hear what the other person has to say. You will have time to decide later whether the feedback fits you or not. Here are some tips for receiving feedback that may help you get more out of the experience:

- Focus on being present rather than preparing what you want to say: Give yourself time to consider the feedback if you find yourself taking it personally or feel too emotionally charged in the moment. In most situations, delaying your response is fine—it usually indicates that you are thinking seriously about the feedback.

- Practice active listening: Encourage the speaker to express all of their thoughts and hear them thoroughly. People speak more freely when they are uninterrupted and when they feel the listener is engaged and paying attention. Getting more information will help you get a clearer picture of the message. People often start out tentatively when giving feedback because they expect the listener to be guarded and defensive too. Acting in a way that contradicts this expectation may serve to facilitate more open conversation [see Active Listening for more].

Getting “defensive”

When others attempt to share their views with us, we may hear them as judgments or criticism, which may cause us to feel threatened. When we perceive something as threatening, we tend to adopt a “fight, flight, or freeze” response—our brains are hard-wired to react that way. Fight represents an aggressive reaction to defend yourself, flight conveys avoidance, and freeze represents passive acceptance in the moment to avoid further instigation of the perceived threat. This can also be described as “getting defensive.”

However, even when others intend to convey disapproval in their feedback, the outcome can be changed dramatically by altering how we appraise the situation and how we react. In fact, many feedback situations that trigger us to feel anxious or defensive may not really be threatening at all. We may seek out or create negativity that is not intended.

How you interpret feedback can make it a painful or empowering experience. For example, interpreting feedback as critical, static, or final can cause you to become unnecessarily defensive or lead you to feel as though you’ve failed in your objectives.

If you have “analysis paralysis,” meaning you tend to over-think the feedback you receive, feedback can feel more harmful than helpful. In contrast, interpreting feedback as informational, dynamic, or changeable helps you take charge.

No matter what has been said, once you have listened to the feedback, it’s up to you how you want to move forward.

Interpreting intentions

Often, we take feedback differently based on our interpretations of the other person’s intentions. That is, if we interpret the feedback as serving a “helpful” function or having “good” intentions, we tend to personalize it less.

On the other hand, when we perceive feedback as having “bad” intentions, being “unfair,” unnecessarily “harsh,” or merely critical, we tend to internalize and/or personalize the feedback more. It bears mentioning that it is usually difficult to evaluate our hypotheses or “mind-read” the other person’s intent without checking with them.

Gender differences

Studies suggest that women are more likely than men to internalize negative feedback and take responsibility for perceived failures or mistakes. Women, more often than men, externalize positive feedback and attribute successful performance to chance, luck, or environmental factors such as “having a good day” or encountering an easy grader.

Conversely, men are more likely to attribute their success to their own competence and hard work and their failures to situational and environmental factors. This suggests that regardless of the intention of the person providing the feedback, men and women often treat the message itself differently.

The way that feedback is interpreted differently by women and other marginalized groups may be related to stereotype threat. Negative stereotypes may cause women, people of color, and individuals with other minority identities, to evaluate themselves poorly, thereby affecting the way they perform on tasks.

For example, when women are told that they perform poorly in math when compared to men, they score lower on math-based tasks. When women and people of color receive negative or constructive feedback, they may fear that the feedback is not based on personal merits, but rather is rooted in negative stereotypes. This therefore decreases motivation to improve on such tasks.

Gender differences are also apparent in the quality of feedback that women receive. Research shows that women are more likely to be told “white lies” in performance feedback; they are more likely to be given kinder, yet less honest, feedback. This phenomenon is likely due to gender stereotypes about the sensitivity of women.

While this kind feedback may feel good in the moment, leading to feelings of pride and satisfaction, it ultimately may not promote growth. To advance in your field, receiving constructive feedback from an expert in your chosen field will benefit you more than insincere yet positive feedback.

Therefore, when receiving positive feedback from a faculty member, it may be helpful to ask for additional, more constructive feedback. Here are some examples:

- Thank you for your kind evaluation of my proposal. Could you provide a few examples of areas that I could improve?

- I appreciate you noting the strengths in my experiment. What do you perceive as areas that need improvement?

Asking for additional feedback from faculty members will demonstrate your willingness to grow within your field. In fact, individuals who seek out feedback experience more positive emotions in response to feedback. The more accustomed to feedback you are, the easier it becomes to view it as a tool for growth, rather than a personal offense.

Reframing feedback to work for you

Feedback, whether constructive, positive, or negative, can elicit a variety of emotional reactions. When receiving positive feedback, you may feel pride, satisfaction, or relief. You may even experience embarrassment due to societal expectations of humility.

On the other hand, negative and constructive feedback can provoke feelings of hopelessness, anger, anxiety, and shame. While these emotions may be unpleasant, constructive feedback can also foster feelings of hope. When constructive feedback is viewed as a strategy for improvement and personal growth, students may feel optimistic about their ability to persist in their field.

How you choose to interpret feedback can affect how you think, feel and act. Some experts suggest that all feedback is constructive because it may be considered as a source of confirming or disconfirming evidence that can help you in some way.

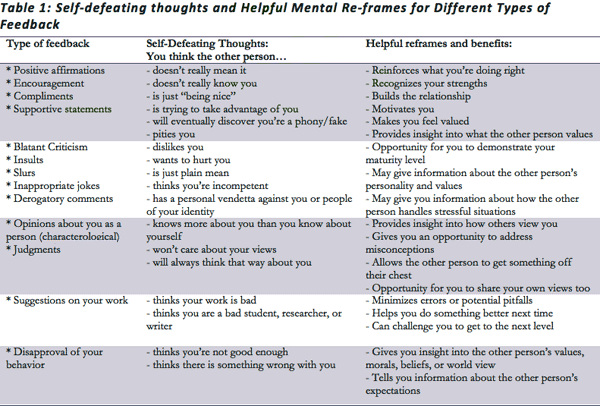

One tool for making even the most negative feedback useful is to use reframing statements, that is, formulating more constructive ways to think about what happens. Reframing statements offer us some control over how we choose to perceive and interpret situations.

Table 1 offers some illustrations of negative thoughts that may come after hearing feedback, and some examples of how to reframe them in a manner that will help you to adequately perceive and gain control of the feedback situation.

When you don’t have control

While reframing thoughts can give you more control of a feedback situation, there are going to be times when a person’s feedback is about something outside of your control. For example, you cannot reason with someone who dislikes you or views you as incompetent primarily because you are a woman or member of a minority group. Research suggests that in fields where women are outnumbered, it still takes very little data for a woman to be viewed as incompetent and, conversely, a great deal of success to be perceived as competent.

Here are five ways to regain control of a feedback situation:

- Try using a mental reframe: remind yourself of what you do well.

- Find what you can control: ask the person to clarify their concerns and help you understand what you can work on.

- Accept that you cannot change or control the other person: focus on your own thoughts and feelings.

- Take what you can learn from the feedback: choose an interpretation that will help you meet your goals.

- Ask yourself if the feedback is due to bias and/or sexism.

Receiving feedback can be a positive experience, no matter what is shared. Interpreting any feedback you receive as a way to improve can be empowering and can facilitate increased self-growth. However, any interpretations that allow you to feel put down or emphasize what you don’t have control over can reduce your self-efficacy—your belief in your own ability to accomplish something—which, in turn, reduces motivation.

Deciding if feedback fits

Passively accepting feedback that doesn’t make sense to you or doesn’t fit can lead to lower self-worth, interpersonal misunderstandings, conflict, further criticism, and/or a lost opportunity to learn from the feedback experience. Just because you heard the feedback, even if you said nothing when you received it, doesn’t mean that you must choose to accept it.

Saying nothing in spite of disagreeing with feedback, however, may indicate to the other person that you agree with them if you leave it unaddressed over time. Thus, one of the most important aspects of interpreting feedback is deciding whether the feedback fits you or not.

Ask yourself, how does this feedback fit with …

- what the person has said about me in the past?

- what others have said about me in the past?

- how others who are important in my life see me?

- my own views of myself?

- examples or evidence from similar situations in the past or present?

Other questions to consider:

- What are other people’s experiences receiving feedback from this person?

- Do they tend to give a certain kind of feedback, have a certain style of delivery, or target certain groups?

- Does the feedback contain microaggressions, sexism, gendered racism, or other forms of bias?

- Are there some parts of the feedback that may fit but others that don’t?

Once you have decided whether and how the feedback fits, you can then move on to the task of deciding how to respond. The following section addresses strategies you can use to respond to feedback and the impression your response may make.

Self-test

Angie submits a draft of her manuscript to her advisor for review. He flips through it and exclaims, “Looks good. Probably would be a lot better if you weren’t so busy.”

How should Angie interpret this feedback?

- A. Her writing quality is only mediocre, not good enough for academia.

- B. Her advisor thinks she is a great writer with a lot of potential.

- C. She needs more clarification to decide what this means.

- D. Her advisor thinks her busy schedule is getting in the way of her work.

How you respond to feedback can be a reflection of your personality and interpersonal communication style just as the way that someone delivers feedback to you reflects something about them. The part we usually don’t think about is how much choice we have in how we respond to what they have to say.

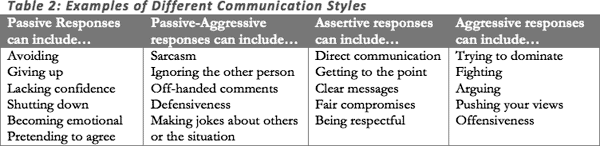

We can choose to use strategies that are assertive to convey a direct, succinct, and clear response to others that eliminates confusion and helps others see our point of view [see Expressing Yourself], or we can choose other options, such as passive, aggressive, or passive-aggressive responses which tend to convey more indirect messages [Also see Assertiveness]. Out of these communication styles, assertive responses to feedback are most likely to initiate a respectful dialogue between both parties. Table 2 indicates examples of each of these communication styles.

Once you have decided whether or not the feedback you have received fits, you can choose the best way to respond. Keep in mind that even an assertive message may not always elicit the ideal response from the other person because you cannot control the other person’s interactional style.

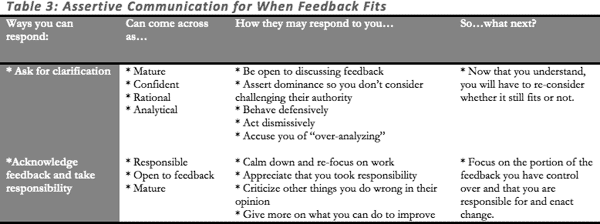

However, assertiveness can help you protect your boundaries regardless of how the other person chooses to respond. Tables 3 & 4 describe possible scenarios of how you can assertively communicate when you perceive that someone’s feedback does or does not fit.

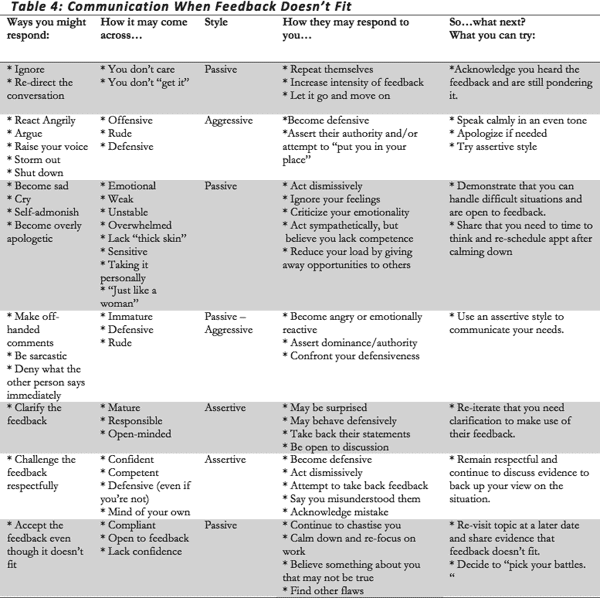

Table 4 below provides examples of using the various communication styles for responding to feedback that does not fit. To reiterate, assertive responses to feedback are most likely to start a productive and respectful conversation.

However, when feedback does not fit with our own or others’ perceptions of us, we may feel defensive and tend towards less favorable forms of communication, such as passive, aggressive, or passive-aggressive communication. This is particularly likely if you are not used to communicating assertively.

If you initially respond using passive, passive-aggressive, or aggressive communication, remember to have self-compassion. We are all human!

See the final column of Table 4 for ideas on how to redirect the conversation after less favorable forms of communication were used.

The role of verbal and nonverbal match in responding to feedback

Verbal and nonverbal forms of communication influence the message. Depending on the match or mismatch between your verbal message (the spoken content) and your nonverbal message (e.g., body posture, tone of voice). The message may be interpreted in an entirely different manner [see Active Listening and Expressing Yourself for more on verbal-nonverbal mismatch].

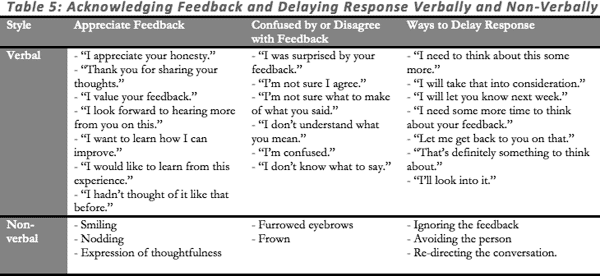

Verbal and nonverbal communication are not mutually exclusive concepts. You can use any combination of statements and nonverbal means to convey or modify a message.

Verbal communication that is congruent with nonverbal communication is most likely to convey a clear message, Table 5 illustrates ways that you can acknowledge feedback and delay your response verbally and/or nonverbally.

Ten tips on responding thoughtfully to feedback:

To get the most out of a conversation on feedback and attain your objectives, consider trying out these techniques [see Planning the Message for more on how to prepare your response.]:

- Respond to the most salient points of feedback rather than trying to address everything.

- Recognize what you have control over and accept when you cannot change the situation. Learn from your mistakes, try to improve where possible, and let go when there is nothing you can do.

- Discuss your reactions calmly and assertively even when you are presented with “curve balls” or unexpected issues.

- Convey confidence about your expertise verbally and non-verbally [see Expressing Yourself].

- Make your response deliberate rather than just reacting to what is said. Sometimes delaying the response may give you more time to consider the feedback and plan your reply.

- Reframe self-defeating thoughts. [See Table 1 above]

- Build on strengths rather than on weaknesses. For example, discuss what was helpful about the conversation or say something like, “So I’m hearing you say that I have some strengths but if I were to improve in this area, that would make me even stronger.”

- Clarify what you heard directly rather than “mind reading” or guessing what the other person thinks. This can:

- clear up a potential misunderstanding AND

- bring to the other person’s attention that the statement came across in a certain way [see Active Listening to learn more about paraphrasing and perception-checking] .

- Separate intent from impact. Although you may feel hurt by someone’s feedback, the intent in conveying the feedback may not have been to cause harm.

- Discuss whether the feedback fits using evidence and examples of past feedback and performance.

Differences in power may be another factor that impacts your decisions when responding to feedback. An individual with power has the ability to influence the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of others.

Individuals with power typically hold a resource that is valued by another person, making that person dependent on the power holder. In doctoral programs, faculty members hold power, and the valued resource is academic and career success.

Advisors have the ability to shape your career development and opportunities. This is made more complicated when faculty members have privileged identities that afford them power; for example, a white, male faculty member holds significant power over a doctoral student who is a woman of color. When responding to feedback, it may be important to consider the power differential within the relationship, and how your response may impact that dynamic.

Responding to feedback in an aggressive manner may sever your relationship with this faculty member, which could have negative implications. Yet, remaining passive usually comes with an emotional cost. Responding respectfully, yet assertively, may be an effective “middle ground” between these options.

Although the best tactic often is to be thoughtful and diplomatic, it’s also important to know when feedback is not intended to be helpful or reflects bias. Experiences with subtle sexism or microaggressions based on stereotyped views of women still abound, especially in environments with few women.

Although they may not be illegal like sexual harassment or constitute actionable discrimination, they are nonetheless inappropriate and often harmful to their targets. If you think gendered and racialized expectations are operating in the feedback you’re getting and that you don’t have control in the situation, you can evaluate the severity of the behavior and respond accordingly.

For more information, visit Recognizing Sexism and Microaggressions. You will find tools for understanding how bias may be impacting your feedback and learn strategies for intervening.

Self-test

Sarah has recently met with her advisor, Dr. Scott, who seemed upset that their experiment hadn’t gone as planned. Although he didn’t blame her directly, he was curt with her during their conversation so she was confused as to whether he felt she was responsible or not.

Sarah decided to spend the latter half of the meeting listening to what Dr. Scott had to say and trying to see the situation from his point of view. It seemed to have helped because he calmed down toward the end of the meeting.

After leaving his office, she explored how she felt about the situation. She remembered him saying, “I know you worked on this, but I had really been counting on you to monitor the hormone levels so that this wouldn’t happen.”

Sarah interpreted Dr. Scott’s feedback as meaning that he believed she made a mistake on her part of the experiment. However, after discussing the situation with her trusted labmate, Amanda, Sarah felt that Dr. Scott’s feedback didn’t fit her.

Amanda reminded Sarah about how frustrated she had been when Dr. Scott had focused all his attention on the guys in the lab and had been dismissive of her whenever she had questions. Sarah realized that although she was responsible for making sure the numbers were right, she had taken numerous steps to reach out and ask her advisor for guidance, clarification, and help when needed but had been largely ignored.

Among the following options, what is the best way for Sarah to respond during their next meeting?

- A. Apologize to Dr. Scott for her mistake and explain that she is working on improving for next time.

- B. Decide to ignore the issue for the time being because his anger would have passed by then.

- C. Discuss her other research during the meeting and then, next time they’re in the lab, point out to Dr. Scott when he has not addressed her questions so he can start to realize how his behavior is contributing to the problem.

- D. Acknowledge responsibility for errors on her part and let Dr. Scott know that getting his guidance when she has questions is important to her. Propose ways to prevent future problems.

Learning to receive and respond to feedback deliberately is a valuable professional skill that may help you to navigate potentially tough situations. Feedback is important because it provides information about how you are perceived, how you might improve, and about the person delivering it. Although you cannot control what types of feedback you will receive, the way in which you interpret and respond to the feedback is entirely within your control.

- View feedback as an opportunity to learn about yourself, both from what others share with you and from how you choose to react.

- Practice interpreting feedback from multiple perspectives and as if it has multiple possible meanings. Just because someone says something about you, does not mean you have to accept it or even that it is true.

- Practice ways to respond to both positive and negative feedback. Doing so will allow you to learn as much as possible from the situation and will help you to be prepared should you find yourself in a situation where you are surprised or taken aback by feedback that you receive.

Bear, J. B., Cushenberry, L., London, M., & Sherman, G. D. (2017). Performance feedback, power retention, and the gender gap in leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(6), 721-740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.02.003

Cohen, G. L., Steele, C. M., & Ross, L. D. (1999). The mentor's dilemma: Providing critical feedback across the racial divide. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(10), 1302–1318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167299258011

Correll, S. J., & Simard, C. (2016, April 29). Research: Vague feedback is holding women back. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/04/research-vague-feedback-is-holding-women-back. .

Fogliati, V. J., & Bussey, K. (2013). Stereotype threat reduces motivation to improve: Effects of stereotype threat and feedback on women's intentions to improve mathematical ability. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(3), 310-324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684313480045

Fong, C. J., Schallert, D. L., Williams, K. M., Williamson, Z. H., Warner, Ja. R., Lin, S.., & Kim, Y. W. (2018). When feedback signals failure but offers hope for improvement: A process model of constructive criticism. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 30, 42-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2018.02.014

Fong, C. J., Warner, J. R., Williams, K. M., Schallert, D. L., Chen, L-H.,Williamson, Z. H., & Lin, S. (2016). Deconstructing constructive criticism: The nature of academic emotions associated with constructive, positive, and negative feedback. Learning and Individual Differences, 49, 393-399. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.05.019

Guinote, A. (2017). How power affects people: Activating, wanting, and goal seeking. Annual Review of Psychology, 68(1), 353–381. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044153

Hattie, J. & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Jampol, L. & Zayas, V. (2021). Gendered white lies: Women are given inflated performance feedback when compared with men. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47(1), 57-69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167220916622

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

McCuen, R. H., Akar, G., Gifford, I. A., & Srikantaiah, D. (2009). Recommendations for improving graduate adviser-advisee communication. Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice, 135(4). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1052-3928(2009)135:4(153)

O'Meara, K., Knudsen, K., & Jones, J. (2013). The role of emotional competencies in faculty-doctoral student relationships. The Review of Higher Education, 36(3), 315-347. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2013.0021

Palaganas, J. C., & Edwards, R. A. (2021). Six common pitfalls of feedback conversations. Academic Medicine, 96(2), 313. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003767

Park, L. E., Kondrak, C. L., Ward, D. E., & Streamer, L. (2018). Positive feedback from male authority figures boosts women’s math outcomes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(3), 359-383. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217741312

Wang, T., & Li, L. Y. (2011). ‘Tell me what to do’ vs. ‘guide me through it’: Feedback experiences of international doctoral students. Active Learning in Higher Education, 12(2), 101-112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787411402438

The importance of being open and honest with your advisor.

Hearing from Students and Having an Impact

The importance of giving back to students and making an impact in their future education and career choices.

Highlights the obstacles faced when trying to have research reviewed by the advisor and emphasizes the steps necessary to make adequate progress in the program.

Suggestions for defining research.

Words of Wisdom: Dr. Anderson-Rowland

The importance of finding a good advisor and making sure to get everything in writing.

Dealing with Assumptions and Accusations (Short Version)

Being accused of cheating and regrets about not being more assertive.

The Importance of Having Positive Working Relationships: A Case Study

The importance of good working relationships and when it's worth putting forth effort.

Communicate Effectively

Explains that satisfaction comes from working with students and the opportunity to make new disco

Explains that satisfaction comes from working with students and the opportunity to make new disco

The importance of learning from mistakes and persisting despite setbacks.

The importance of learning from your effort, regardless of the outcome.

Advice on how to seek out support in graduate school and how to bounce back from setbacks.

Shares the excitement that comes from collaborating with others to make new discoveries.

Elaborates on the standard practice of science despite cultural differences.

Strategies for negotiating as a faculty member.

When it's time to graduate and when it's important to start learning on the job.

Highlights the transition into graduate level science where the answers aren't known.

The importance of goal setting and using others' experiences to make strong choices about your own p

Advice for balancing research and fun in graduate school.

Advice for students: stay focused, ask questions, and remain open-minded when working with others.

How to adapt experimental methods to match a lifestyle.

How to negotiate a schedule for raising a family and overcoming setbacks in a new career.

The importance of giving yourself credit and remembering why you are doing what you're doing.

The importance of peer relationships and the learning process that takes place despite concrete outc

Working with graduate students is a rewarding aspect of being a faculty member.

Advice for graduate students on how to maintain their confidence, courage, and dignity.

Emphasizes peer relationships and departmental climate.

How to handle being accused of having an affair with the advisor.

Explains an interdisciplinary branch of physics and the passion for research, service, and teaching.

Teaching as the impetus for work.

Discusses necessary precautions to take as a female student working late nights on campus.

Discusses necessary precautions to take as a female student working late nights on campus.

Being accused of cheating and regrets about not being more assertive.

Being accused of cheating and regrets about not being more assertive.

The importance of self-authorship and using graduate school as a process for self-definition.

Reminder that support can be found in unexpected places.

Urges female graduate students to persist in the field of mathematics because the field needs divers

How being unaware of being the only woman was advantageous to program success.

Alternatives to departmental isolation and the importance of networking.

Environmental issues faced in academia.

The importance of first impressions in choosing a graduate program.

Satisfaction comes from interacting with intelligent people across cultures.

Adjusting physical appearance to fit in with peers.

The importance of remembering that graduate school is only one part of a larger career.

Describes an incident of receiving a lower grade than a man for similar work.

The opportunity for freedom, growth, and collaboration as a faculty member.

How to survive the aftermath of a sexual harassment incident.

Highlights the gendered assumptions encountered as a faculty member.

The Importance of Having Positive Working Relationships: A Case Study

An alternative way to approach being the only woman in a given situation.

Contributions to the field are reflected through choices.

The importance of sharing stories of sexual harassment with others to gain support.

The importance of finding the right advisor to support your research goals.

How to handle being accused of having an affair with the advisor.

Explains when to confront a problem and when it may be better to maneuver around it.

How to be upfront, direct, and assertive when confronting instances of sexual harassment.

Highlights the universal customs of science.

Class performance builds confidence to remain in program.

Captures the annoyance of male colleagues making sexist assumptions and the challenges with conferen

The importance of recognizing the progress that has been made by women in science fields.

Advice for accomplishing your academic goals without making unnecessary compromises.

Emphasizes the challenge with saying no, but the importance of learning to do so.

How to make friends with colleagues to encourage a supportive environment.

Underscores the challenges that come from being the only woman in an academic department and gives s

Highlights an experience in which peers were not only colleagues, but also friends.

How the physical space in a laboratory allowed for collaboration among colleagues.

The importance of a good leader in setting standards for diversity, climate, and tenure policies.

How to observe others' reactions to subtle comments in order to gauge an appropriate response.

Urges students not to get wrapped into issues that do not directly involve them.

Departmental reactions to the choice to have children.

How to refute sexist comments and challenge gendered assumptions.

The importance of sharing stories of sexual harassment with others and realizing that you are not al

Confronting a male colleague with contradictory findings at a conference.

How colleagues can assist in making the transition into graduate life easier by sharing information

Captures the small but noticeable annoyances that come with being the only woman.

The importance of picking your battles to avoid unfair labeling.

Reminder that it is not necessary to feel comfortable socially to do good science.

Gender stereotypes faced in getting into graduate school and conducting research.

How to seek support from administrators outside the department when dealing with departmental sexism

The first realization that being a woman in science was outside the norm.

Challenges of being international and female, particularly with regards to an academic career and th

Suggestions for how to deal with sexist comments.

Playing a variety of roles as the only woman in the department.

The process of establishing yourself in the same department as your spouse.

Emphasizes positive peer relationships within her cohort.

The challenges of working in male-dominated academic environments and the negative stereotypes assoc

The feasibility of pursuing a family and science.

The importance of hearing other people's stories.

The importance of understanding priorities and allocating resources accordingly.

Advises how to keep family informed about research goals and progression from student to faculty mem

Explains some of the setbacks in dating relationships.

Advises students to continue to pursue their education because the payoff is self-respect.

The importance of believing in yourself, admitting your mistakes, and continuing to do what you love

How to accept non-traditional relationships and lifestyles in academia.

Notes the challenges of a dual career marriage and the obstacles in fighting for tenure and balancin

The process of overcoming setbacks related to career options and personal relationships.

How to balance motherhood responsibilities in graduate school.

The importance of supportive peer relationships.

Being married in graduate school and having children as a faculty member.

Advisor's experiences encourage well-informed career decisions.

The importance of a supportive network of colleagues.

Doing something useful to make a difference and how to appreciate a happy, supportive work environme

Taking time off before pursuing her PhD.

How a supportive department and a modified teaching schedule allowed for maternity leave.

How to sustain taking time off and pursuing the PhD later in life.

Advises how to keep family informed about research goals and progression from student to faculty mem

The importance of a supportive extended family in helping to balance school and children.

The importance of having a number of things in your life that bring you joy and satisfaction.

Understanding your strengths and weaknesses, but ultimately giving yourself recognition for your suc

The importance of learning over time and remaining positive in the face of criticism.

Motivation for doing work: interacting with students and doing research that can make a difference i

Emphasizes the challenge with saying no, but the importance of learning to do so.

The importance of remaining passionate and remembering that the PhD opens doors.

The importance of defining clear goals, remaining self-confident, and learning to say no.

The importance of allowing yourself the opportunity to change your mind and reconsider your goals.

The importance of knowing what you want and expecting tradeoffs on the path to get it.

Making discoveries and collaborating with others brings satisfaction.

Creating a schedule and meeting an advisor's expectations.

Advises graduate students to take a semester off if they choose to have a child because it is too ch

Explains the role children play in career choices.

Using leisure activities to relieve stress and build friendships.

The satisfaction that comes from working with colleagues and interacting with others.

The decision to get married in graduate school.

The importance of maintaining a balanced lifestyle to alleviate stress.

Addresses personal relationship sacrifices.

The importance of nurturing relationships outside of academia.

Explains the choice to have children in graduate school.

Challenges with being married to a fellow academician and finding faculty positions.

How a flexible schedule as a professor made it possible to have a family and a career.

The importance of evaluating your priorities to create balance and happiness.

Appreciation for advisor's assistance in transitioning to the US.

Emphasizes the joy in working with others and giving back to society.

Chronicles the evolution of a career over time.

Suggestions for how to increase women's participation in science with an emphasis on policy change.

The importance of being open and honest with your advisor.

How a positive advisor challenged his students to think for themselves.

Highlights the obstacles faced when trying to have research reviewed by the advisor and emphasizes t

The importance of having a variety of mentors throughout your graduate experience.

Challenges faced with establishing yourself as an independent researcher separate from an influentia

The importance of asking questions and searching for creative solutions to new problems.

The importance of finding a good advisor and making sure to get everything in writing.

Challenges in confronting the advisor with news of pregnancy.

Experiences with an international advisor.

How to maintain good relationships with colleagues while being motivated to finish the program qu

The importance of giving back to students and making an impact in their future education and care

An Arizona State University project, supported by the National Science Foundation under grants 0634519, 0910384 and 1761278

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. © 2021 CareerWISE. All rights reserved. Privacy | Legal

Comments

We want to hear from you. Did this page remind you of any experiences you’ve had? Did you realize something new? Please take a moment to tell us about it—and we’ll keep it confidential.