Communicate More Effectively

Career Wise Menu

Understand Communication Elements: Gender in Communication

- Learn to recognize gendered communication styles and habits.

- Learn to identify gender stereotypes and expectations in communication.

- Learn to understand the relationship between gender, language, and power.

“The test for whether or not you can hold a job should not be the arrangement of your chromosomes.” —Bella Abzug

“Women are not inherently passive or peaceful. We're not inherently anything but human.” —Robin Morgan

Over decades, researchers have demonstrated how gender influences nearly every aspect of living. This module focuses primarily on the social construction of gender and how it is salient for women in STEM. Specifically, it considers how the gendered roles and expectations that society ascribes to women impact the communication process.

There are also social consequences, for women who do not fit gender stereotypes (Phelan et al., 2008). As a woman in a male-dominated field, gender is an omnipresent and important factor in communication processes. Gender dynamics (including gendered language, gender socialization, and gender stereotyping) shape how messages in communication are both presented and interpreted (see Planning the Message and Expressing Yourself). Stereotypically female styles of interacting, such as communicating with warmth and openness, may be beneficial in some situations; however, research suggests that conforming to gender stereotypes can be damaging when these behaviors are in conflict with expectations for leaders and other role expectations (Eagly, 2007; Catalyst, 2007). There are also social consequences, for women who do not fit gender stereotypes (Phelan et al., 2008). Ultimately, language and communication reflect, maintain, and even create the social roles and power structures that lead to gender inequities. Becoming more aware of how gender dynamics affect communication can help you gain perspective on your experiences and be more effective in attaining the outcomes you want.

Self-test

To me, being a woman:

- A. has very little to do with how I communicate

- B. means that I will always be treated as an inferior by the men in my field.

- C. will ultimately prevent me from reaching my career goals.

- D. influences communication in different ways according to the circumstances.

For many, gender dynamics are so deeply entrenched in our thinking, everyday language and ways of interacting that they go unrecognized and are taken for granted [See Recognize Sexism]. When being a woman is an advantage, such as when you stand out favorably in a sea of men in your field, gender still makes a difference in your experience. Considering how gender operates in your daily life is important to fully understanding the process of communication.

Differences in styles of interacting contribute to gender dynamics in communication. Despite common notions of difference, women and men are more alike than different on most dimensions (Barnett & Rivers, 2004; Hyde, 2005; Wright, 2006). However, in U.S. culture women are generally socialized to seek or prefer (Tannen, 1990):

- Support (over status)

- Intimacy (over independence)

- Understanding (over advice)

- Feelings (over information)

- Proposals (over demands)

- Compromise (over conflict)

Additionally, women are more likely to demonstrate communication skills such as:

- Displaying empathy

- Listening carefully

- Showing sensitivity to interpersonal differences

- Giving constructive feedback

- Offering support

Overall, what society defines as feminine characteristics is more conducive than masculine characteristics to making others feel comfortable and building close relationships. In many cases, these characteristics and styles are also highly beneficial in the work environment (O’Neill et al., 2002). In fact, some employee training programs focus on developing the above stereotypically feminine communication skills in employees.

Other stereotypical feminine styles of interacting are less beneficial in the workplace as they can signal that women are less confident and/or capable of being in a leadership position (also see Expressing Yourself, The Impression You Make, and Your Personality and Preferences). Examples include (Lakoff, 1975; Wolfe & Powell, 2009):

The use of qualifying “hedges” (e.g., “It seems like...” “Maybe we should consider...” “I’m not sure, but...”)

- Being indirect

- Stating information in the form of a question as opposed to a statement

- Being silent

Keep in mind that the actual empirical differences between men and women may be less important than how people respond to these perceived differences. You may find that many people act as though gender differences are fixed and deterministic, even though their rationale for doing so may not be valid.—it may in fact be nothing more than following a gender stereotype.

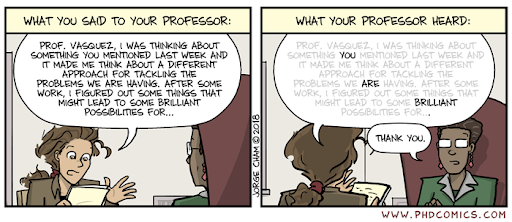

Stereotypes play a strong role in the gender dynamics of communication. Stereotypes are assumptions and expectations placed on you by others based on your gender or other outwardly visible aspects of your identity. Stereotyping usually occurs without awareness or bad intention: it is generally automatic and unconscious (Banaji & Hardin, 1996; Banaji et al., 2001; Greenwald et al., 2002). Thus, even if you do not demonstrate typically feminine styles of interacting, people still consciously or unconsciously expect you to behave as a woman and interpret your behaviors differently based on these stereotypes. For example, what may look like assertiveness in a man could be interpreted as aggression in a woman. You are especially at risk of being stereotyped by your gender when you are the only—or one of very few—women represented in your department.

Expectations about what it means to be a woman conflict with expectations about what it means to be a good leader and what it takes to get ahead in the workforce. Finding the balance between these types of opposing forces is what effective communication is about in a gendered context.

The implicit message to women is: “be more confident if you want to get ahead! But not too much, it’s not ladylike; people won’t like you.” This is an example of a double bind: a communication dilemma in which an individual receives two or more conflicting messages, with one message canceling out the other. The double bind can prevent the individual from changing her situation because making a change in one area negatively affects another area. Research has suggested that this double bind is especially disadvantageous for women in an interview setting (Phelan et al., 2008).

The point is you are not going to be able to please everyone. Sometimes breaking out of or conforming to stereotypes means developing your own unique styles of communication that are useful to you as an individual (and may not work for everyone else). YOU are the person this all has to work for.

Feminists and sociologists argue that language and communication reflect, maintain, and even create social roles and power structures, including gender inequity (Crawford, 2001; Weatherall, 2002). For example, they argue that despite efforts to reinforce alternatives, the English language tradition of using the terms “man” and “he” to refer to both men and women reflects the position of men in our society as “regular” people, the standard whereby women are the “other”—a “subtype.” Instead of being understood as their own entity, women are then always defined in relation to men and specifically in opposition to them (Du Gay, 2007).

Names and titles send a strong message about power and status. Women are continually and differentially (Benokraitis, 1997) addressed in ways that reflect their perceived or assumed inferior status to men. For example, grown women are commonly addressed as “girl” in the media and in everyday interactions. In academic settings, women professors are still addressed by their first or married names rather than by Dr. or Professor. The use of gendered language is not just limited to face-to-face interactions. In fact, studies have shown that men and women use different language features, functions, and style in written and online communication (Thomson, 2006).

To help combat the use of gendered language in your field, try to use gender-neutral terms in your speech and writing. This shows others in your department that you make a concerted effort to keep sexism out of your field and sets a precedent for how people should treat you. This may include modeling more equitable gender terms for students or colleagues (e.g., using “ombudsperson” instead of “ombudsman”) and reminding your students how you prefer to be addressed. Again, ultimately you teach others how to treat you.

You can prevent negative stereotypes and expectations from becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy by trusting in yourself and your abilities. Remember that whatever you believe about yourself is usually what others will eventually come to believe about you as well.

Banaji, M. R., & Hardin, C. D. (1996). Automatic stereotyping. Psychological Science, 7(3), 136-141. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00346.x

Banaji, M. R., Lemm, K. M., & Carpenter, S. J. (2001). The social unconscious. In M. Hewstone & M. Brewer (Series Eds.) & A. Tesser & N. Schwartz (Vol. Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Vol.1. Individual processes (pp. 134–158). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Barnett, R. & Rivers, C. (2004). Same difference: How gender myths are hurting our relationships, our children, and our jobs. New York: Basic Books. https://dx.doi.org/10.15365/joce.1004132013

Benokraitis, N.V. (1997). Subtle sexism: current practices and prospects for change. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Burleson, B. R., Kunkel, A. W., Samter, W., & Working, K. J. (1996). Men's and women's evaluations of communication skills in personal relationships: When sex differences make a difference and when they don't. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 13(2), 201-224. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0265407596132003

Catalyst (2007). The double-bind dilemma for women in leadership: Damned if you do, doomed if you don’t. New York: Catalyst.

Cohen, E. D. (2018). Gendered styles of student-faculty interaction among college students. Social science research, 75, 117-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.06.004

Crawford, M. (2001). Gender and language. In R. K. Unger (Ed.), Handbook of the psychology of women and gender (pp. 228– 244). New York: Wiley.

Du Gay, P. (2007). Organizing Identity: Persons and organizations ‘after theory.’ London: Sage. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446211342

Eagly, A. H. (2007). Female leadership advantage and disadvantage: Resolving the contradictions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00326.x

Greenwald, A. G., Banaji, M. R., Rudman, L. A., Farnham, S. D., Nosek, B. A., & Mellott, D. S. (2002). A unified theory of implicit attitudes, stereotypes, self-esteem, and self-concept. Psychological Review, 109(1), 3-25. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.109.1.3

Gunter, R., & Stambach, A. (2005). Differences in men and women scientists' perceptions of workplace climate. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering, 11(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.1615/JWomenMinorScienEng.v11.i1.60

Holleran, S. E., Whitehead, J., Schmader, T., & Mehl, M. R. (2011). Talking shop and shooting the breeze: A study of workplace conversation and job disengagement among STEM faculty. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2(1), 65-71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550610379921

Hyde, J. S. (2005). The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychologist, 60(6), 581-592. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.581

Kacewicz, E., Pennebaker, J. W., Davis, M., Jeon, M., & Graesser, A. C. (2014). Pronoun use reflects standings in social hierarchies. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 33(2), 125-143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X13502654

Lakoff, R. T. (1975). Language and woman’s place. New York: Harper & Row. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4166707

Leaper, C., & Robnett, R. D. (2011). Women are more likely than men to use tentative language, aren’t they? A meta-analysis testing for gender differences and moderators. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35(1), 129-142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684310392728

Maji, S., & Dixit, S. (2020). Exploring self-silencing in workplace relationships: A qualitative study of female software engineers. The Qualitative Report, 25(6), 1505-1525. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr

O'Neill, K. S., Hansen, C. D., & May, G. L. (2002). The effect of gender on the transfer of interpersonal communication skills training to the workplace: Three theoretical frames. Human Resource Development Review, 1(2), 167-185. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315583839-14

Phelan, J. E., Moss-Racusin, C. A., & Rudman, L. A. (2008). Competent yet out in the cold: Shifting criteria for hiring reflect backlash toward agentic women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(4), 406-413. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00454.x

Stout, J. G., & Dasgupta, N. (2011). When he doesn’t mean you: Gender-exclusive language as ostracism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(6), 757-769. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211406434

Tannen, D. (2007). You just don’t understand: Women and men in conversation. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Thomson, R. (2006). The effect of topic of discussion on gendered language in computer mediated communication discussion. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 25(2), 167-178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X06286452

Von Hippel, C., Wiryakusuma, C., Bowden, J., Shochet, M. (2011). Stereotype threat and female communication styles. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(10), 1312-1324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211410439

Weatherall, A. (2002). Gender, language and discourse. Hove England; New York: Routledge.

Wessel, J. L., Hagiwara, N., Ryan, A. M., & Kermond, C. M. (2015). Should women applicants “man up” for traditionally masculine fields? Effectiveness of two verbal identity management strategies. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 39(2), 243-255. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684314543265

Wolfe, J., & Powell, E. (2009). Biases in interpersonal communication: How engineering students perceive gender typical speech acts in teamwork. Journal of Engineering Education, 98(1), 5-16. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2009.tb01001.x

Wright, P. H. (2006). Toward an expanded orientation to the comparative study of women’s and men’s same sex friendships. In K. Dindia & D. J. Canary (Eds.), Sex differences and similarities in communication (2nd edition). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Being Comfortable as a Woman Among Men

Emphasizes positive peer relationships within her cohort.

Ways to Cope with Minor Issues Related to Being a Woman

How to observe others' reactions to subtle comments in order to gauge an appropriate response.

An alternative way to approach being the only woman in a given situation.

The pros and cons of being the only woman in a department and the importance of setting boundaries and knowing your own limitations.

The first realization that being a woman in science was outside the norm.

How being unaware of being the only woman was advantageous to program success.

Hidden Differences in Academic Culture (Extended)

Environmental issues faced in academia.

Captures the annoyance of male colleagues making sexist assumptions and the challenges with conference travel as a female graduate student.

Communicate Effectively

Explains that satisfaction comes from working with students and the opportunity to make new disco

Explains that satisfaction comes from working with students and the opportunity to make new disco

The importance of learning from mistakes and persisting despite setbacks.

The importance of learning from your effort, regardless of the outcome.

Advice on how to seek out support in graduate school and how to bounce back from setbacks.

Shares the excitement that comes from collaborating with others to make new discoveries.

Elaborates on the standard practice of science despite cultural differences.

Strategies for negotiating as a faculty member.

When it's time to graduate and when it's important to start learning on the job.

Highlights the transition into graduate level science where the answers aren't known.

The importance of goal setting and using others' experiences to make strong choices about your own p

Advice for balancing research and fun in graduate school.

Advice for students: stay focused, ask questions, and remain open-minded when working with others.

How to adapt experimental methods to match a lifestyle.

How to negotiate a schedule for raising a family and overcoming setbacks in a new career.

The importance of giving yourself credit and remembering why you are doing what you're doing.

The importance of peer relationships and the learning process that takes place despite concrete outc

Working with graduate students is a rewarding aspect of being a faculty member.

Advice for graduate students on how to maintain their confidence, courage, and dignity.

Emphasizes peer relationships and departmental climate.

How to handle being accused of having an affair with the advisor.

Explains an interdisciplinary branch of physics and the passion for research, service, and teaching.

Teaching as the impetus for work.

Discusses necessary precautions to take as a female student working late nights on campus.

Discusses necessary precautions to take as a female student working late nights on campus.

Being accused of cheating and regrets about not being more assertive.

Being accused of cheating and regrets about not being more assertive.

The importance of self-authorship and using graduate school as a process for self-definition.

Reminder that support can be found in unexpected places.

Urges female graduate students to persist in the field of mathematics because the field needs divers

How being unaware of being the only woman was advantageous to program success.

Alternatives to departmental isolation and the importance of networking.

Environmental issues faced in academia.

The importance of first impressions in choosing a graduate program.

Satisfaction comes from interacting with intelligent people across cultures.

Adjusting physical appearance to fit in with peers.

The importance of remembering that graduate school is only one part of a larger career.

Describes an incident of receiving a lower grade than a man for similar work.

The opportunity for freedom, growth, and collaboration as a faculty member.

How to survive the aftermath of a sexual harassment incident.

Highlights the gendered assumptions encountered as a faculty member.

The Importance of Having Positive Working Relationships: A Case Study

An alternative way to approach being the only woman in a given situation.

Contributions to the field are reflected through choices.

The importance of sharing stories of sexual harassment with others to gain support.

The importance of finding the right advisor to support your research goals.

How to handle being accused of having an affair with the advisor.

Explains when to confront a problem and when it may be better to maneuver around it.

How to be upfront, direct, and assertive when confronting instances of sexual harassment.

Highlights the universal customs of science.

Class performance builds confidence to remain in program.

Captures the annoyance of male colleagues making sexist assumptions and the challenges with conferen

The importance of recognizing the progress that has been made by women in science fields.

Advice for accomplishing your academic goals without making unnecessary compromises.

Emphasizes the challenge with saying no, but the importance of learning to do so.

How to make friends with colleagues to encourage a supportive environment.

Underscores the challenges that come from being the only woman in an academic department and gives s

Highlights an experience in which peers were not only colleagues, but also friends.

How the physical space in a laboratory allowed for collaboration among colleagues.

The importance of a good leader in setting standards for diversity, climate, and tenure policies.

How to observe others' reactions to subtle comments in order to gauge an appropriate response.

Urges students not to get wrapped into issues that do not directly involve them.

Departmental reactions to the choice to have children.

How to refute sexist comments and challenge gendered assumptions.

The importance of sharing stories of sexual harassment with others and realizing that you are not al

Confronting a male colleague with contradictory findings at a conference.

How colleagues can assist in making the transition into graduate life easier by sharing information

Captures the small but noticeable annoyances that come with being the only woman.

The importance of picking your battles to avoid unfair labeling.

Reminder that it is not necessary to feel comfortable socially to do good science.

Gender stereotypes faced in getting into graduate school and conducting research.

How to seek support from administrators outside the department when dealing with departmental sexism

The first realization that being a woman in science was outside the norm.

Challenges of being international and female, particularly with regards to an academic career and th

Suggestions for how to deal with sexist comments.

Playing a variety of roles as the only woman in the department.

The process of establishing yourself in the same department as your spouse.

Emphasizes positive peer relationships within her cohort.

The challenges of working in male-dominated academic environments and the negative stereotypes assoc

The feasibility of pursuing a family and science.

The importance of hearing other people's stories.

The importance of understanding priorities and allocating resources accordingly.

Advises how to keep family informed about research goals and progression from student to faculty mem

Explains some of the setbacks in dating relationships.

Advises students to continue to pursue their education because the payoff is self-respect.

The importance of believing in yourself, admitting your mistakes, and continuing to do what you love

How to accept non-traditional relationships and lifestyles in academia.

Notes the challenges of a dual career marriage and the obstacles in fighting for tenure and balancin

The process of overcoming setbacks related to career options and personal relationships.

How to balance motherhood responsibilities in graduate school.

The importance of supportive peer relationships.

Being married in graduate school and having children as a faculty member.

Advisor's experiences encourage well-informed career decisions.

The importance of a supportive network of colleagues.

Doing something useful to make a difference and how to appreciate a happy, supportive work environme

Taking time off before pursuing her PhD.

How a supportive department and a modified teaching schedule allowed for maternity leave.

How to sustain taking time off and pursuing the PhD later in life.

Advises how to keep family informed about research goals and progression from student to faculty mem

The importance of a supportive extended family in helping to balance school and children.

The importance of having a number of things in your life that bring you joy and satisfaction.

Understanding your strengths and weaknesses, but ultimately giving yourself recognition for your suc

The importance of learning over time and remaining positive in the face of criticism.

Motivation for doing work: interacting with students and doing research that can make a difference i

Emphasizes the challenge with saying no, but the importance of learning to do so.

The importance of remaining passionate and remembering that the PhD opens doors.

The importance of defining clear goals, remaining self-confident, and learning to say no.

The importance of allowing yourself the opportunity to change your mind and reconsider your goals.

The importance of knowing what you want and expecting tradeoffs on the path to get it.

Making discoveries and collaborating with others brings satisfaction.

Creating a schedule and meeting an advisor's expectations.

Advises graduate students to take a semester off if they choose to have a child because it is too ch

Explains the role children play in career choices.

Using leisure activities to relieve stress and build friendships.

The satisfaction that comes from working with colleagues and interacting with others.

The decision to get married in graduate school.

The importance of maintaining a balanced lifestyle to alleviate stress.

Addresses personal relationship sacrifices.

The importance of nurturing relationships outside of academia.

Explains the choice to have children in graduate school.

Challenges with being married to a fellow academician and finding faculty positions.

How a flexible schedule as a professor made it possible to have a family and a career.

The importance of evaluating your priorities to create balance and happiness.

Appreciation for advisor's assistance in transitioning to the US.

Emphasizes the joy in working with others and giving back to society.

Chronicles the evolution of a career over time.

Suggestions for how to increase women's participation in science with an emphasis on policy change.

The importance of being open and honest with your advisor.

How a positive advisor challenged his students to think for themselves.

Highlights the obstacles faced when trying to have research reviewed by the advisor and emphasizes t

The importance of having a variety of mentors throughout your graduate experience.

Challenges faced with establishing yourself as an independent researcher separate from an influentia

The importance of asking questions and searching for creative solutions to new problems.

The importance of finding a good advisor and making sure to get everything in writing.

Challenges in confronting the advisor with news of pregnancy.

Experiences with an international advisor.

How to maintain good relationships with colleagues while being motivated to finish the program qu

The importance of giving back to students and making an impact in their future education and care

An Arizona State University project, supported by the National Science Foundation under grants 0634519, 0910384 and 1761278

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. © 2021 CareerWISE. All rights reserved. Privacy | Legal

Comments

We want to hear from you. Did this page remind you of any experiences you’ve had? Did you realize something new? Please take a moment to tell us about it—and we’ll keep it confidential.