Communicate More Effectively

Career Wise Menu

Learn Communication Skills: Negotiate

- Learn to understand the components of an effective negotiation plan.

- Learn to approach negotiation in an effective and confident manner.

- Learn to engage effectively in negotiation.

- Learn to avoid common pitfalls to negotiation.

- Learn to understand and navigate situations in which gender plays a role in negotiation.

Negotiation is a discussion between two or more people that involves two main functions: identifying a common ground and reaching an explicit agreement regarding a matter of mutual concern. It’s an advanced strategy that relies on the mastery of basic communication skills. However, although negotiation is thought to be an experience, like being at the “negotiating table,” it is actually an active process, it happens almost every day in the academic environment and the workplace—we just may not always recognize it. In fact, we negotiate lots of things in our work and research, including asking for expanded roles and opportunities, seeking support to move ahead, asking for resources (e.g., time, funding, assistance) to get work done, agreeing on goals and objectives, and claiming credit for our work.

This module will help you become aware of aspects of negotiation that you should consider as a woman in a science, technology, engineering, or math field, and it will teach you some guidelines and steps for navigating the negotiation process effectively.

Self-test

Before a negotiation, you would most likely...

- A. Think a lot about the conversation…and hope that it goes well, although you feel unsure about the possible outcome

- B. Think a lot about the conversation…and feel confident about presenting the different solutions that you came up with

- C. Think a lot about the conversation…and see if there are any options to getting out of having it

- D. Think a lot about the conversation…and become extremely anxious—you’d just rather not think about it at all

As a woman in a science, technology, engineering, or math environment, you face some unique challenges when it comes to negotiation. Maybe you’ve noticed instances in the past when you felt you needed to negotiate for something—more resources, a deadline extension, even extra lab time or access to equipment—but for whatever reason, you backed off. Unfortunately, this is common for women. In fact, research has shown that women are less likely to initiate negotiations than men (Babcock & Laschever, 2007) but also that the gender gap has become narrower and context-bound (Kugler, Reif, Kaschner, & Brodbeck, 2018).

Even passing on a single negotiation can have lifelong consequences. As Babcock and Laschever (2007) calculated, at age 25, the difference between Michael’s negotiated 3% per year salary bump versus Melissa’s non negotiated 2% per year raises results in Melissa’s earning 68% less than Michael after 40 years.

So what keeps women from negotiating? Research points to gender role socialization. Society sends messages about how men and women are and should be. We see portrayals of both genders in the media, and they differ significantly. All you have to do is turn on the TV to see examples of men and women at home and in the workplace, and see their roles and the activities in which they participate—and those differences are still pretty stark, even after much progress. Further, women pick up messages in their professional experiences conveying a gender bias that makes it risky to become too successful.

Studies have also demonstrated that women tend to develop what psychologists call an external locus of control; that is, women are more likely to believe that others or external factors control their circumstances, while men are more likely to believe that they can influence their circumstances and opportunities through their own actions. As a result, many women tend to carry the perception that their circumstances are fixed and less negotiable than they really are. Rather than be assertive and proactive about entering negotiation, women may tend to think that their performance alone will be enough to bring them the opportunities and recognition they deserve.

Women are particularly effective in negotiating for time and flexibility, especially when they feel that what is good for them is also good for their group. Women also outperform men in negotiating on behalf of others. Women initiate negotiations more readily when there is less situational ambiguity that negotiation is appropriate and when negotiation is cast as a collaborative activity, more aligned with their gender role (Kugler et al., 2018).

Some men may find a hardworking, talented woman to be very threatening. Women may also encounter faculty and peers who assume that they are less capable than their male counterparts in science and engineering fields dominated by men. These beliefs on the parts of others may enter into the negotiation process. What women may not realize is that their collaborative, integrative nature can make them better negotiators because they know how to balance their interests with others’ interests—strengths that benefit them provided they assert themselves and ask for what they need.

As a woman, your negotiations will often require raising awareness of gender issues and pushing back on gendered stereotypes and practices, even when you’re not addressing gender directly. For example, in the workplace, by negotiating a flexible time arrangement, you may also reveal how your organization’s practices make it difficult for mothers to succeed. In the university environment, negotiating for a leadership role in your lab or research group can simultaneously call attention to the fact that women have been overlooked. Claiming value for “invisible” work in your lab can show how bias operates in performance reviews and even authorship consideration. You can see that while negotiation is a critical skill for everybody, it’s an especially important function for women—it can give you the means to counter the effects of gender bias.

Culture can also play an important role in how a negotiation unfolds. Culture can influence how someone interprets power dynamics with important stakeholders, favors different types of negotiation (i.e., face-to-face discussion vs. using a mediator), can affect goals set for a negotiated outcome (i.e. individual vs. collective). A successful negotiator will consider these types of cultural values.

Consider the following example:

Dr. Xu heavily critiques every assignment I turn in. In class, I felt like she picked on me more than other students and was always challenging my analyses or asking me to rewrite my papers. Finally, I got really frustrated and I planned to talk with her about how unfair I thought she was being with me and about possibly changing advisors. I told my labmate about my plan to talk to Dr. Xu about it and she looked terrified! She told me that in her home country (she and Dr. Xu were actually from the same province), criticism is a sign that the professor thinks you have great potential and that you’re worth his or her time and energy—a high honor and compliment.

In this example, culture is clearly playing a role in the interactions between these two individuals. If she were to negotiate for a different advisor, or even for her current advisor to change her style of feedback, culture would be an important factor for consideration. Cultural nuances like this and other examples don’t have to be mysterious. Most of the time, you’ve probably had a reasonable amount of contact with this particular person so you can predict responses and communication style by your past experiences. Also keep in mind that sometimes these mannerisms are a reflection of personal style rather than their respective culture.

Keep the following in mind as you approach your negotiations.

Evaluate the need for negotiation

If you are in a situation where the prospects are worse if NO agreement takes place, then it may be a good idea to consider negotiating. The following four questions will help you to assess this.

Ask yourself, “If I do nothing, …”:

- Will I feel good about myself?

- Will I feel good about the situation?

- Will I be able to live with the situation the way it is for the duration of my graduate school experience?

- Will the situation, as it is, enhance important aspects of my academic experience (e.g., research productivity, my grades, my progress, my funding, etc.)?

If you answered “no” to one or more of these questions, negotiating may be a good option for you, because doing nothing means things will most likely remain the same.

Plan your negotiation

Negotiation involves preparation. Good preparation involves considering the following criteria:

- What’s at stake: what are your objectives? What are the other person’s objectives?

- Alternatives: what are your alternatives to negotiation? What are the other person’s alternatives?

- Potential negotiated outcomes: Is there a potential solution that could satisfy both parties’ objectives better than the alternatives to negotiation?

- Costs: What will it cost you to negotiate? What do you expect to lose in terms of tangible resources (e.g., funding, letters of recommendation)? Will negotiating set a bad precedent?

- Implementation: If you do reach an agreement, is there a reasonable prospect that it will be carried out?

During your preparation, you should brainstorm different solutions that not only seem viable for you, but will also seem reasonable to the other party. Avoid getting stuck on one “right” answer. [See the Use Brainstorming module].

Do your homework

Be clear on what is expected from you; investigate the departmental norms or precedents set by your peers or preceding student cohorts (See Planning Your Message). If you are clear on what the expectations are, you’ll find that negotiation is an easier and more straightforward process. Have relevant information ready to discuss. Know what your on-the-books “rights” are, as well as what is typical informal department policy on such things. This will help you predict a response in advance and manage the situation better. Remember: knowing your rights as a student or employee in some cases is the most important thing you can do to empower yourself in negotiation situations.

Engaging in negotiation

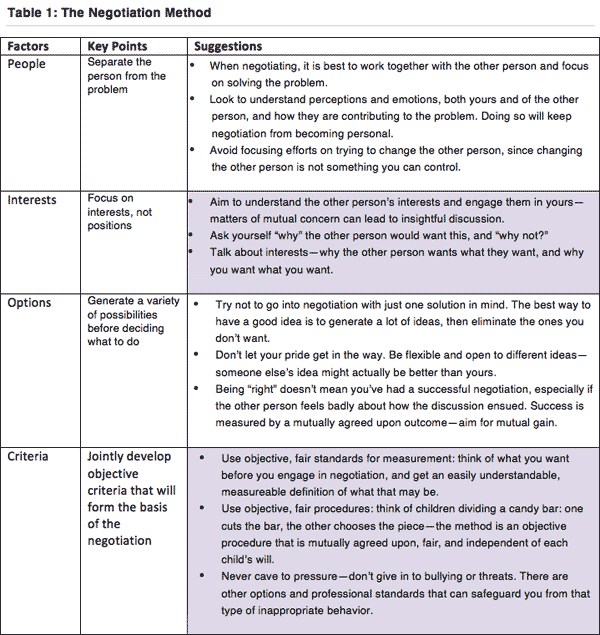

Experts suggest that there are four important factors to keep in mind when negotiating, each of which entails something to think about (i.e., some planning) and something to do (i.e., some action): people, interests, options, and criteria. Table 1 gives a summary of each factor, along with suggestions for implementation.

Self-test

Your lab partner has been using the only computer that has the upgraded software for analyzing data for his dissertation. But you also need it to do your part of your project.

- A. Carefully broach the issue and see how it goes

- B. Find somewhere else to do your analysis

- C. First discuss what he thinks might work to address this issue and present some solutions that you thought about as well

- D. Get resentful that he’s not being very considerate but say nothing

Be flexible

Flexibility is an important component of negotiation given that negotiation usually involves multiple stakeholders.

Be prepared and willing to look at the problem from multiple angles and consider multiple options for solution. Be ready to bring in mutually agreed-upon third party individuals as consultants, if necessary. The best way to deal with difference is to look for areas that are low-risk to you, high-reward to the other person, and vice versa.

You can also “fractionate” or break your problem or situation down into smaller parts that seem more negotiable. It is important to separate substantive issues (i.e. what the problem is really about) from process issues (i.e. being afraid of how someone else will react to this issue).

Develop a BATNA

A BATNA is your “Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement”. It’s what you are and are not willing to settle for. Before entering into any negotiation. it will help you to know your BATNA in advance. A BATNA is like an insurance policy, a strong fallback position that you determine in advance. This essentially gives you two options: one, you are successful in getting what you want, or two, you already have a good alternative plan.

For example, if you know you’ll need to negotiate with your lab mates for time to use the lab’s specialized equipment for a project and you have an approaching deadline, you’ll know in advance the days you need to use the lab as well as when it’s too late, as well as the days that absolutely will not work for you. If you have a BATNA, you can judge how the negotiation is going and if you’ve achieved what is acceptable to you. This doesn’t mean you need to settle for your BATNA. It merely enables you to explore a wider range of options, be creative, and be flexible. Having only one solution leaves you and the other party in a bind.

Anticipate Your outcomes

Having a plan doesn’t just entail thinking about different solutions. A plan also includes rehearsing how you will respond to things. You should be aware of your possible reactions or how you will feel if you do or don’t get what you intended. In planning, try to cover all the angles and possible scenarios [see Planning Your Message].

Decide:

- If____ happens, I will _____.

Or:

- If I see that ______will not work, I will suggest we revisit this at another time so that I don’t close the door on this discussion.

Remember: It’s okay to delay.

Walk yourself through your plan. You may also want to imagine how you will negotiate and accept a Plan B or C or how you will responsibly reject an unworkable plan, but stay away from visualizing catastrophe. Don’t engulf yourself in negative scenarios or get consumed with anxious emotions. If you are well prepared, negotiation won’t get to that level.

Don’t analyze crucial concerns alone. Get advice and support from other people. Practicing what you want to say with a trusted friend or family member will make you feel more confident when the time comes to have the actual conversation.

Decide what is NOT negotiable to you

Although not everything in your program is up for negotiation, you may have some issues that are non-negotiable for you. That’s OK—it shows that you know how to set limits, provided that you don’t set outrageous ones.

For example, if you can’t stay after 4pm because your daughter does competitive gymnastics, you’ll have to figure out how to integrate your values into the values of your program. Maybe you can come in an hour early or make up hours on another day so you can leave at 4pm, since the predominant value of your lab is productivity.

Self-test

Your lab group has a tight deadline for your grant deliverables. You’ve been working day and night it seems! However, your vacation (that you requested several months ago) is next week. You know it’s coming in the midst of a very hectic time, but you already have travel plans. When you reminded your advisor of this, he got very upset with you and told you you’re not being a “team player” then stormed out of the lab. He hasn’t talked to you since and you’re not sure the status of your leave time now.

- A. Try and catch him at a better time and do your best to have a positive interaction with him so he’s not mad when you leave.

- B. Schedule a meeting and ask what happened. You obviously had some type of miscommunication that needs to be cleared up.

- C. Just quietly leave on your planned vacation and hopefully he’ll be over it when you get back.

- D. Forget about your vacation and just keep working through the deadline.

Be aware of your “Gendered Lens”

Sometimes women have different interpersonal styles, so negotiation with male colleagues, supervisors, or advisors can present challenges. You both may be looking at the situation through different lenses and using different strategies [see Gender for more]. You do not need to mirror your male counterpart’s style, but be aware of where you are coming from. Sometimes ambitious women have negative self-perceptions or evaluate themselves critically or harshly because they have few messages in their environment that are positively affirming or reinforcing.

Affirmations and words of encouragement are rare in academic environments, particularly in departments and disciplines that are dominated by men. Sometimes STEM women don’t think of themselves as ambitious or efficacious or even competent because they are in a competitive environment. Don’t let this happen. You’re in graduate school—of course you are motivated, able, and accomplished!

Have an exit plan

Above all, you’ll want to keep your cool so that if you find yourself in a hostile situation, it’s best to have an exit plan. Even if you decide that someone is being unreasonable, you will want to have rational reactions and thoughtful responses. Don’t let a curve ball response in a negotiation send you into a tailspin. Have an exit plan for a negotiation that doesn’t go well, like, “It appears we’ve reached an impasse,” or “Maybe we should revisit this at another time.” It’s okay to have a “what happened?” conversation at a later time to defuse any unresolved issues from a difficult negotiation, particularly where your objectives were not met at all.

Document your agreements

A verbal agreement is great but a written one is better. This doesn’t have to mean having a signed contract, but documenting the agreement in some way is important. This can mean having a work plan set up that entails mutual expectations, dates, and tasks. You can take notes on the negotiated plan and give the other person(s) a copy later or send an email describing the agreement so that people can let you know if you or they have misinterpreted something. This makes things clear and puts it in writing for future reference.

Self-test

If you found out you are pregnant and you work in a wet lab with potentially harmful chemicals, you would likely need to make some important decisions about whether you should change your working conditions for the health of the baby. Some of these decisions would involve the input of others. As a member of the lab group, you would need to negotiate for changes in your responsibilities in the short-term and in the long-term. Yes, you will be making some changes but most likely you will also need some concessions on the part of the program, your advisor, and your labmates—all very important stakeholders.

- A. I’ll need to find out what my rights are as an employee and a student as well as what might be hazardous to me. Given that information, my personal needs, and taking into consideration our collective scope of work, I’ll present different solutions.

- B. I’ll let the discussion guide my planning. When I tell my advisor that I am pregnant, I’ll take his suggestions and plan around those. That way some of the decision-making is up to him and not just me.

- C. I’ll work until my pregnancy becomes an issue to others. This way I don’t have to inconvenience anyone unfairly and I can try to avoid things that I think may be harmful to me.

- D. I think I’ll just quit so that I don’t have to deal with all the different reactions I’ll get. I’m concerned that I’ll get fired anyway because I cannot fulfill the scope of work that was originally set out for our lab.

Negotiation has to reflect both your personal style and what will work within the system you are in. However, in order to achieve an important goal, you may have to move outside your comfort zone. This means that when entering a negotiation, you may experience some discomfort, but the end goal should be a respectful and workable compromise that involves mutual gain.

In academia, we expect a more even playing field, since both women and men achieve their positions presumably based on ability and performance. But competence and achievements aren’t always the only basis for being evaluated or making progress. As a woman in a STEM field, you will face inherently different issues in negotiation than your male counterparts. Recognizing that there are inequities in the academic system will help you form appropriate plans of action.

- You don’t have to keep your negotiation plans to yourself—it’s important to run important issues and how you plan to handle them by someone you trust. They may serve as an important “reality check” or have a different perspective that can inform your process.

- Negotiation is both an art and a skill that relies heavily on basic communication skills. See the modules on Planning Your Message, Active Listening, Expressing Yourself, Receiving and Responding to Feedback, and Assertiveness to help you expand and refine your negotiation toolbox.

Amanatullah, E., & Morris, M. (2010). Negotiating gender roles: Gender differences in assertive negotiating are mediated by women’s fear of backlash and attenuated when negotiating on behalf of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(2), 256–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017094

Amanatullah, E., & Tinsley, C. (2013). Punishing female negotiators for asserting too much…or not enough: Exploring why advocacy moderates backlash against assertive female negotiators. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 120(1), 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2012.03.006

Babcock, L., & Laschever, S. (2007). Women don’t ask: The high cost of avoiding negotiation and positive strategies for change. New York: Bantam Dell.

Bowles, H., & Babcock, L. (2013). How can women escape the compensation negotiation dilemma? Relational accounts are one answer. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(1), 80–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684312455524

Bowles, H., Babcock, L., & McGinn, K. (2005). Constraints and triggers: Situational mechanics of gender in negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(6), 951–965. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.951

Deaux, K., & Farris, E. (1977). Attributing causes for one’s own performance: The effects of sex, norms, and outcome. Journal of Research in Personality, 11(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(77)90029-0

Eriksson, K., & Sandberg, A. (2012). Gender differences in initiation of negotiation: Does the gender of the negotiation counterpart matter? Negotiation Journal, 28(4), 407–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1571-9979.2012.00349.x

Fisher, R., Ury, W., & Patton, B. (2011). Getting to yes: Negotiating agreement without giving in (3rd ed). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Kolb, D. M., & McGinn, K. (2009). Beyond gender and negotiation to gendered negotiations. Negotiation and conflict management research, 2(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-4716.2008.00024.x

Kugler, K. G., Reif, J. A. M., Kaschner, T., & Brodbeck, F. C. (2018). Gender differences in the initiation of negotiations: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 144(2), 198–222. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000135

Kulik, C., & Olekalns, M. (2012). Negotiating the gender divide: Lessons from the negotiation and organizational behavior literatures. Journal of Management, 38(4), 1387–1415. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311431307

Kulik, C. T., Sinha, R., & Olekalns, M. (2020). Women-focused negotiation training: A gendered solution to a gendered problem. In Research Handbook on Gender and Negotiation. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788976763.00027

Mazei, J., Hüffmeier, J., Freund, P., Stuhlmacher, A., Bilke, L., & Hertel, G. (2015). A meta-analysis on gender differences in negotiation outcomes and their moderators. Psychological Bulletin, 141(1), 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038184

Netchaeva, E., Kouchaki, M., & Sheppard, L. (2015). A man’s (precarious) place: Men’s experienced threat and self-assertive reactions to female superiors. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(9), 1247–1259. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215593491

Reif, J., Kunz, F., Kugler, K., & Brodbeck, F. (2019). Negotiation contexts: How and why they shape women’s and men’s decision to negotiate. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 12(4), 322–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/ncmr.12153

Schneider, A. K. (2017). Negotiating while female. SMUL Law Review, 70, 695. https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol70/iss3/6

Seligman, L., Anderson, R., Ollendick, T., Rauch, S., Silverman, W., Wilhelm, S., & Woods, D. (2018). Preparing women in academic psychology for their first compensation negotiation: A panel perspective of challenges and recommendations. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice, 49(4), 282–289. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000204

Shan, W., Keller, J., & Joseph, D. (2019). Are men better negotiators everywhere? A meta‐analysis of how gender differences in negotiation performance vary across cultures. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(6), 651–675. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2357

Stone, D., Patton, B., & Heen, S. (1999). Difficult conversations: How to discuss what matters most. New York, NY: Viking Penguin.

Toosi, N., Mor, S., Semnani-Azad, Z., Phillips, K., & Amanatullah, E. (2019). Who can lean in? The intersecting role of race and gender in negotiations. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 43(1), 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684318800492

An Example of How to Negotiate (Part 2)

Strategies for negotiating as a faculty member.

Suggestions for defining research.

Captures the annoyance of male colleagues making sexist assumptions and the challenges with conference travel as a female graduate student.

Highlights the obstacles faced when trying to have research reviewed by the advisor and emphasizes the steps necessary to make adequate progress in the program.

Compromises Outside the Realm of Children

Addresses personal relationship sacrifices.

Words of Wisdom: Dr. Anderson-Rowland

The importance of finding a good advisor and making sure to get everything in writing.

I Have Not Figured Out How to Say "No"

Emphasizes the challenge with saying no, but the importance of learning to do so.

Communicate Effectively

Explains that satisfaction comes from working with students and the opportunity to make new disco

Explains that satisfaction comes from working with students and the opportunity to make new disco

The importance of learning from mistakes and persisting despite setbacks.

The importance of learning from your effort, regardless of the outcome.

Advice on how to seek out support in graduate school and how to bounce back from setbacks.

Shares the excitement that comes from collaborating with others to make new discoveries.

Elaborates on the standard practice of science despite cultural differences.

Strategies for negotiating as a faculty member.

When it's time to graduate and when it's important to start learning on the job.

Highlights the transition into graduate level science where the answers aren't known.

The importance of goal setting and using others' experiences to make strong choices about your own p

Advice for balancing research and fun in graduate school.

Advice for students: stay focused, ask questions, and remain open-minded when working with others.

How to adapt experimental methods to match a lifestyle.

How to negotiate a schedule for raising a family and overcoming setbacks in a new career.

The importance of giving yourself credit and remembering why you are doing what you're doing.

The importance of peer relationships and the learning process that takes place despite concrete outc

Working with graduate students is a rewarding aspect of being a faculty member.

Advice for graduate students on how to maintain their confidence, courage, and dignity.

Emphasizes peer relationships and departmental climate.

How to handle being accused of having an affair with the advisor.

Explains an interdisciplinary branch of physics and the passion for research, service, and teaching.

Teaching as the impetus for work.

Discusses necessary precautions to take as a female student working late nights on campus.

Discusses necessary precautions to take as a female student working late nights on campus.

Being accused of cheating and regrets about not being more assertive.

Being accused of cheating and regrets about not being more assertive.

The importance of self-authorship and using graduate school as a process for self-definition.

Reminder that support can be found in unexpected places.

Urges female graduate students to persist in the field of mathematics because the field needs divers

How being unaware of being the only woman was advantageous to program success.

Alternatives to departmental isolation and the importance of networking.

Environmental issues faced in academia.

The importance of first impressions in choosing a graduate program.

Satisfaction comes from interacting with intelligent people across cultures.

Adjusting physical appearance to fit in with peers.

The importance of remembering that graduate school is only one part of a larger career.

Describes an incident of receiving a lower grade than a man for similar work.

The opportunity for freedom, growth, and collaboration as a faculty member.

How to survive the aftermath of a sexual harassment incident.

Highlights the gendered assumptions encountered as a faculty member.

The Importance of Having Positive Working Relationships: A Case Study

An alternative way to approach being the only woman in a given situation.

Contributions to the field are reflected through choices.

The importance of sharing stories of sexual harassment with others to gain support.

The importance of finding the right advisor to support your research goals.

How to handle being accused of having an affair with the advisor.

Explains when to confront a problem and when it may be better to maneuver around it.

How to be upfront, direct, and assertive when confronting instances of sexual harassment.

Highlights the universal customs of science.

Class performance builds confidence to remain in program.

Captures the annoyance of male colleagues making sexist assumptions and the challenges with conferen

The importance of recognizing the progress that has been made by women in science fields.

Advice for accomplishing your academic goals without making unnecessary compromises.

Emphasizes the challenge with saying no, but the importance of learning to do so.

How to make friends with colleagues to encourage a supportive environment.

Underscores the challenges that come from being the only woman in an academic department and gives s

Highlights an experience in which peers were not only colleagues, but also friends.

How the physical space in a laboratory allowed for collaboration among colleagues.

The importance of a good leader in setting standards for diversity, climate, and tenure policies.

How to observe others' reactions to subtle comments in order to gauge an appropriate response.

Urges students not to get wrapped into issues that do not directly involve them.

Departmental reactions to the choice to have children.

How to refute sexist comments and challenge gendered assumptions.

The importance of sharing stories of sexual harassment with others and realizing that you are not al

Confronting a male colleague with contradictory findings at a conference.

How colleagues can assist in making the transition into graduate life easier by sharing information

Captures the small but noticeable annoyances that come with being the only woman.

The importance of picking your battles to avoid unfair labeling.

Reminder that it is not necessary to feel comfortable socially to do good science.

Gender stereotypes faced in getting into graduate school and conducting research.

How to seek support from administrators outside the department when dealing with departmental sexism

The first realization that being a woman in science was outside the norm.

Challenges of being international and female, particularly with regards to an academic career and th

Suggestions for how to deal with sexist comments.

Playing a variety of roles as the only woman in the department.

The process of establishing yourself in the same department as your spouse.

Emphasizes positive peer relationships within her cohort.

The challenges of working in male-dominated academic environments and the negative stereotypes assoc

The feasibility of pursuing a family and science.

The importance of hearing other people's stories.

The importance of understanding priorities and allocating resources accordingly.

Advises how to keep family informed about research goals and progression from student to faculty mem

Explains some of the setbacks in dating relationships.

Advises students to continue to pursue their education because the payoff is self-respect.

The importance of believing in yourself, admitting your mistakes, and continuing to do what you love

How to accept non-traditional relationships and lifestyles in academia.

Notes the challenges of a dual career marriage and the obstacles in fighting for tenure and balancin

The process of overcoming setbacks related to career options and personal relationships.

How to balance motherhood responsibilities in graduate school.

The importance of supportive peer relationships.

Being married in graduate school and having children as a faculty member.

Advisor's experiences encourage well-informed career decisions.

The importance of a supportive network of colleagues.

Doing something useful to make a difference and how to appreciate a happy, supportive work environme

Taking time off before pursuing her PhD.

How a supportive department and a modified teaching schedule allowed for maternity leave.

How to sustain taking time off and pursuing the PhD later in life.

Advises how to keep family informed about research goals and progression from student to faculty mem

The importance of a supportive extended family in helping to balance school and children.

The importance of having a number of things in your life that bring you joy and satisfaction.

Understanding your strengths and weaknesses, but ultimately giving yourself recognition for your suc

The importance of learning over time and remaining positive in the face of criticism.

Motivation for doing work: interacting with students and doing research that can make a difference i

Emphasizes the challenge with saying no, but the importance of learning to do so.

The importance of remaining passionate and remembering that the PhD opens doors.

The importance of defining clear goals, remaining self-confident, and learning to say no.

The importance of allowing yourself the opportunity to change your mind and reconsider your goals.

The importance of knowing what you want and expecting tradeoffs on the path to get it.

Making discoveries and collaborating with others brings satisfaction.

Creating a schedule and meeting an advisor's expectations.

Advises graduate students to take a semester off if they choose to have a child because it is too ch

Explains the role children play in career choices.

Using leisure activities to relieve stress and build friendships.

The satisfaction that comes from working with colleagues and interacting with others.

The decision to get married in graduate school.

The importance of maintaining a balanced lifestyle to alleviate stress.

Addresses personal relationship sacrifices.

The importance of nurturing relationships outside of academia.

Explains the choice to have children in graduate school.

Challenges with being married to a fellow academician and finding faculty positions.

How a flexible schedule as a professor made it possible to have a family and a career.

The importance of evaluating your priorities to create balance and happiness.

Appreciation for advisor's assistance in transitioning to the US.

Emphasizes the joy in working with others and giving back to society.

Chronicles the evolution of a career over time.

Suggestions for how to increase women's participation in science with an emphasis on policy change.

The importance of being open and honest with your advisor.

How a positive advisor challenged his students to think for themselves.

Highlights the obstacles faced when trying to have research reviewed by the advisor and emphasizes t

The importance of having a variety of mentors throughout your graduate experience.

Challenges faced with establishing yourself as an independent researcher separate from an influentia

The importance of asking questions and searching for creative solutions to new problems.

The importance of finding a good advisor and making sure to get everything in writing.

Challenges in confronting the advisor with news of pregnancy.

Experiences with an international advisor.

How to maintain good relationships with colleagues while being motivated to finish the program qu

The importance of giving back to students and making an impact in their future education and care

An Arizona State University project, supported by the National Science Foundation under grants 0634519, 0910384 and 1761278

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. © 2021 CareerWISE. All rights reserved. Privacy | Legal

Comments

We want to hear from you. Did this page remind you of any experiences you’ve had? Did you realize something new? Please take a moment to tell us about it—and we’ll keep it confidential.