Identify the issue

Career Wise Menu

Understand the Context: Challenges Faced by Sexual and Gender Minorities

- Learn to recognize the common barriers that gender and sexual minority individuals experience in STEM

- Learn about protective factors for LGBTQ individuals in STEM

- Learn to overcome barriers against gender and sexual minorities in STEM through micro interventions

- Learn about forming an advocacy group

“There are so many straight men in my engineering program.”

“When I tried to come out to my Organic Chemistry professor, he told me it was “unprofessional” to discuss my “lifestyle.” The same doesn’t seem to apply to my straight peers who talk about their romantic partners. I feel silenced.”

“The other day, I heard someone in my lab say ‘that’s so gay.’ Now I’m afraid to come out.”

“I heard one of my labmates use a slur against a gay man in our lab. I’m not sure how to intervene.”

“Finding LGBTQ friends on campus has been so rewarding. I feel like I belong now. Without oSTEM, I’m not sure if I would have stayed in my PhD program.”

“I am so glad that the LGBTQ Resource Center connected me to a faculty mentor. It is great seeing another lesbian woman in academia.”

In other modules, you read about how women in STEM programs may experience challenges being in a male-dominated field. Many women experience isolation, hostility, discrimination, and an overall chilly climate. When women in STEM have other marginalized identities, such as Women of Color, gender and sexual minority women, and women with disabilities, they may have additional unique experiences due to intersectionality. Intersectionality describes how systems of oppression, such as sexism, racism, and homophobia, intersect, operate together, and often exacerbate each other.

This module discusses the experiences of being both a woman and LGBTQ in STEM. Whether you are a member of the LGBTQ community yourself, or are looking to serve as an ally to a gender or sexual minority peer, this module will provide insight into the barriers encountered by LGTBQ STEM students, as well as strategies to overcome those barriers.

In this module, we will use the term “gender and sexual minority,” as well as the term LGBTQ. The LGBTQ umbrella includes a wide variety of unique identities. Here is a glossary with important terms to note.

Not only is there a wide variety of sexual and gender identities within the LGBTQ community; individuals with those identities also come from a wide variety of backgrounds, experiences, and identities in terms of race, ability status, SES, etc. It is important to note that much of the research on the experiences of LGBTQ individuals in STEM focuses on white, cisgender individuals. Be sure to read the intersectionality section below to learn about how individuals within the LGBTQ community may be affected differently based on other salient identities.

Members of the LGBTQ community in STEM may encounter additional challenges in their graduate programs that their peers do not. If you are a member of a gender or sexual minority in a STEM graduate program, think through the following questions. If you do not identify as a member of the LGBTQ community, imagine the following questions from the perspective of an LGBTQ peer.

Have you:

- heard anti-LGBTQ language from your professors or peers?

- experienced heteronormativity in your graduate program, or a feeling that heterosexuality is viewed as the norm, with little tolerance for other identities?

- felt isolated in your graduate program due to your sexual or gender identity? Have you ever felt ignored or like you didn’t belong because of these identities?

- felt pressure to “pass” as heterosexual and/or cisgender in your graduate program?

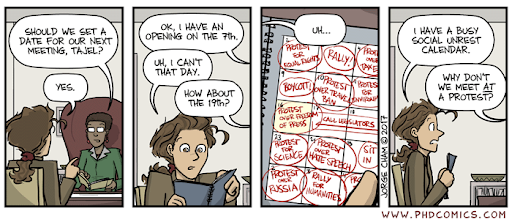

- felt pressure to keep your academic and social lives separate due to your sexuality and/or gender identity?

- received messages that talking about your sexual or gender identity is unprofessional?

- felt that your work was devalued or not respected due to your sexual or gender identity?

- encountered barriers in your STEM program due to your sexuality or gender identity that made you question your place in STEM?

If you answered yes to these questions, you are not alone. Research has demonstrated that many LGBTQ students in STEM encounter these experiences. Because STEM professions are considered technical, gender and sexual minority individuals may receive messages that issues of equality and therefore LGBTQ identities are too social to discuss in the STEM world, and therefore are irrelevant. Some LGBTQ students feel silenced or ignored because of this (Cech & Waldzunas, 2011; Linley, Renn, & Woodford, 2018).

While transgender and gender-nonconforming (TGNC) individuals fall under the LGBTQ umbrella, their experiences may differ from cisgender sexual minority STEM students. TGNC individuals may feel pressured to use their deadname or incorrect pronouns. They may encounter individuals deliberately using incorrect pronouns, or making disparaging remarks about their identities. While sexual and gender minority individuals in STEM may feel a lack of belonging in their programs, there are ways to seek out sources of acceptance and community. You will read about those below.

As mentioned above, intersectionality matters when considering the experiences of LGBTQ students in STEM. LGBTQ individuals with disabilities and LGBTQ individuals of color may have different experiences than white, able-bodied gender and sexual minority individuals. Here are some examples of gender/sexual minority students with additional marginalized identities and how they experience their graduate programs.

- Elizabeth is a pansexual woman who uses a wheelchair. She is a first year PhD student studying Biology. On her way to an oSTEM meeting, she finds that the building is physically inaccessible. She is late to the meeting because it is difficult for her to find an entrance with a ramp.

- Jordan is a Black lesbian woman studying Chemistry. She went to the LGBTQ resource center at her Predominantly White Institution (PWI) and found there were no other LGBTQ people of color in the center. She struggles to find a space or community that is accepting of all of her identities.

- Mentors: finding mentors who provide a sense of support and acceptance can be beneficial in helping you navigate barriers that arise in a STEM doctoral program. LGBTQ faculty members in particular may serve as confidantes and provide a source of support, leading to increased feelings of belonging.

- Looking for LGBTQ mentors? Your campus LGBTQ resource center may help connect you with gender and sexual minority faculty members. Find an LGBTQ campus center here.

- Community: LGBTQ STEM students who feel a sense of belonging are more likely to persist in their degree programs. LGBTQ peers on campus can serve as a vital source of support in navigating challenges that arise in a STEM program

- Looking to find a community? See the Online Resources and Supports module.

- STEM Identity: Feelings of competence in your field and recognition as a member of your field create a strong sense of STEM identity (Carlone & Johnson, 2007; Hughes, 2018). STEM identity increases feelings of belonging and motivation to persist in a STEM program.

- Looking to increase your STEM identity? See the Online Resources and Supports module to find professional organizations for members of your field.

It is never the responsibility of individuals who have experienced discrimination to resolve systems of oppression. Regardless, some people find advocating for themselves to be empowering and liberating. Because of the power differential between students and faculty, it can be difficult or unsafe to take on advocacy alone, particularly when addressing climate concerns to faculty. If you feel passionate about advocating for yourself and other gender and sexual minority individuals in STEM, you may wish to form an advocacy group of multiple students to approach faculty and express your needs.

Cooper et al. (2020) developed the following list of guidelines for creating an inclusive environment for gender and sexual minority individuals in biology. Your advocacy group may present these suggestions to faculty as requests in a format such as an open letter, along with any other concerns about program climate you might have.

|

GUIDELINE |

RESOURCES |

|

Learn what the acronym LGBTQ+ encompasses and use the term appropriately |

Here is a comprehensive glossary of terms related to the LGBTQ community: https://lgbtqia.ucdavis.edu/educated/glossary |

|

Learn the specific vocabulary around the LGBTQ identity |

|

|

Foster safe environments for individuals to reveal their identities |

Cooper et al. (2020) suggest that faculty members provide students the opportunity to share their identities and pronouns via a survey. These surveys can be either identifiable or anonymous, and should include an option for “decline to state.” Surveys could inquire about students’ level of comfort with using their name and pronouns in different settings (eg. one-on-one, in the classroom, in the lab, etc.)

The Cooper et al. (2020) supplemental materials include a sample pronoun survey. |

|

Create opportunities for individuals to choose to reveal their name or pronouns |

Faculty members can provide pronoun stickers or name badges to students. These can also be utilized in a conference setting. Here is a site of how the University of California, San Francisco uses pronoun stickers: https://lgbt.ucsf.edu/pronoun-stickers

Here is a site that provides other best practices for names and pronouns: https://lgbt.umd.edu/good-practices-names-and-pronouns

Here is a site about the importance of using pronouns at conferences: https://esa.org/louisville/name-tag-pronouns/ |

|

Be careful not to assume the gender or partner preference of individuals |

Using gender neutral language, such as they/them pronouns, can help establish an environment that is inclusive to individuals with LGBTQ identities. Here are some basic tips for using gender neutral language: https://www.mypronouns.org/inclusivelanguage |

|

View mistakes as learning opportunities |

Mistakes with pronouns, names, or gender preferences may happen. When these happen, it is best to give a quick apology and correct oneself; lingering on the subject can put an undue burden on the TGNC individual or make them uncomfortable. Faculty members can then take steps to avoid the mistake moving forward. Here is an overview of correcting mistakes regarding pronouns: https://www.mypronouns.org/mistakes |

|

Overtly support the LGBTQ community using cues such as Safe Zone Stickers, LGBTQ+ Rainbow Ribbons At Conferences, and an Explicit Mention of LGBTQ+ Individuals |

Here is a link to the Safe Zone Project: https://thesafezoneproject.com/about/ |

|

Familiarize yourself with LGBTQ community and campus resources |

Here is a directory of LGBTQ Community Centers: https://www.lgbtcenters.org/LGBTCenters Here is a directory of LGBT Campus Centers: https://www.lgbtcampus.org/find-an-lgbtq-campus-center LGBTQ Campus Resource Centers play an important role. They may provide LGBTQ students with access to health care and counseling, and they may foster a sense of support and belonging. Many LGBTQ resource centers provide training and education; faculty may be encouraged to attend a training, or request a training for the department as a whole. Your advocacy group may wish to include this as a request. |

|

Be thoughtful about your use of humor and pop culture in the classroom and how it can impact LGBTQ individuals |

Instructors should avoid using jokes that are offensive to LGBTQ individuals and making references to media that portrays negative stereotypes about LGBTQ individuals. |

|

Present LGBTQ role models in science |

Here are links to lists of influential LGBTQ scientists: https://www.osc.org/important-lgbtq-scientists-who-left-a-mark-on-stem-… https://www.sciencemag.org/features/2010/10/closeted-discoverers-lesbia… https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2018/07/05/queer-scientists-history-first-lg… |

|

Be inclusive of LGBTQ identities when designing research |

This website provides an overview of using LGBTQ inclusive language when collecting demographic data: https://lgbt.umd.edu/good-practices-demographic-data-collection |

|

Advocate for LGBTQ inclusive language in publications |

Here is an American Psychological Association style guide for using bias-free language, with sections on gender and sexual orientation: https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/bias-free-language |

As a member of the LGBTQ community in STEM, you may encounter microaggressions, defined by psychologist Derald Wing Sue as "the everyday slights, indignities, put downs and insults that people of color, women, LGBT populations or those who are marginalized experience in their day-to-day interactions with people." See the Microaggressions module for more details and for examples of how bystanders can respond in support of women.

While it should never be the responsibility of individuals who experience oppression to educate others or stop discrimination, some might feel empowered by standing up for themselves. At the same time, faculty members are in a position of power; they play a significant role in a doctoral student’s academic and career advancement. This power differential is amplified when the faculty member is part of a dominant group (i.e. heterosexual individuals), while the student is a member of a marginalized group (i.e. LGBTQ students). Therefore, it is important for students to weigh the benefits and costs of confronting microaggressions. Here are some questions for consideration (Nadal, 2014):

- If I respond, could my physical safety be in danger

- If I respond, will the person become defensive and will this lead to an argument?

- If I respond, how will this affect my relationship with this person (e.g., coworker, family member, etc.

- If I don’t respond, will I regret not saying something?

- If I don't respond, does that convey that I accept the behavior or statement?

Ultimately, if you choose not to confront discrimination, the microaggressions you experienced were not your fault , and you are not in the wrong. You are justified in making the choice that feels most safe and feasible to you.

If you do wish to challenge microaggressions, microinterventions are strategies that have been suggested. Micro interventions are

“the everyday words or deeds, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate to targets of microaggressions (a) validation of their experiential reality, (b) value as a person, (c) affirmation of their racial or group identity, (d) support and encourage-ment, and (e) reassurance that they are not alone.” (Sue, Alsaidi, Awad, Glaeser, Calle, & Mendez, 2019, p. 134).

These micro interventions may also be used by individuals who do not identify as LGBTQ who witness microaggressions. In fact, bystanders who witness unjust behavior, particularly those with privileged identities, can play an important role in combatting discrimination. Allies who are a part of a dominant group (i.e. white, heterosexual men in STEM), may have more power than the targets of the microaggressions.

The following table is adapted directly from Sue et al. (2019) work on micro-interventions. Examples were changed to align with LGBTQ students in STEM.

Situation: Julia, a transgender woman, shares that she will be attending a SWE meeting that afternoon. Bradley, a male cohort member, says “Why? You won’t fit in there.” Julia and Sara, a cisgender, straight classmate, try to intervene. The metacommunication here is that Julia is not a “real woman.”

|

GOAL |

OBJECTIVE |

TACTICS |

EXAMPLES |

|

Make the invisible visible |

Bring awareness to the microaggression |

Undermine the metacommunication. A metacommunication is hidden communication that may be outside of the individual’s conscious awareness. |

Sara says “why do you think that? SWE is inclusive of all women. Julia will fit in just fine.” |

|

Stand up for yourself or others |

Sara says “let’s not say negative things about Julia.” |

||

|

Express that the microaggression was hurtful |

Name and make the metacommunication explicit |

Julia says “you assume that I won’t fit in because I am transgender. It seems like you are implying that I am not actually a woman.” |

|

|

Encourage the individual to consider the meaning/impact of the microaggression |

Challenge the stereotype |

Julia says “I may have been assigned male at birth, but I am still a woman. I always have been.” |

|

|

Broaden the ascribed trait |

Sara says “there’s more than one way to be a woman.” |

||

|

Ask for clarification |

Sara says “What makes you think that? Julia is just as much a woman as anyone else at the SWE meeting.” |

||

|

Julia says “Why wouldn’t I fit in? I am just as interested in engineering as the other women.” |

Situation: David, a straight, cisgender man, is a 2nd year PhD student studying Mechanical Engineering. He is discussing Marvin, a first-year PhD student in the same program who identifies as gay. Marvin is not in the room. Referring to Marvin, David says “He’s too flamboyant to be an engineer. He might as well go be a Gender Studies major like the rest of his people.” Tonya, a bisexual woman, overhears the conversation. As a woman in the LGBTQ community, she feels hurt by the statements. Samuel, a straight male colleague, also witnesses the microaggression. Samuel and Tonya use the following micro-interventions.

|

GOAL |

OBJECTIVE |

TACTICS |

EXAMPLES |

|

Disarm the microaggression |

Stop or deflect the microaggression |

Express disagreement |

Tonya says “I don’t agree with that.” |

|

Encourage the individual who stated the microaggression to immediately consider their actions |

Sam says “That’s just not true.” |

||

|

Communicate your disagreement or disapproval in the moment |

State values and set limits |

Sam says “I value respect and inclusion. While you have the right to express your opinion, using discriminatory language and perpetuating harmful stereotypes, especially when the person is not there to defend themselves, is disrespectful. I ask you to have more respect by not making those comments.” |

|

|

Describe what is happening |

Tonya says “As a bisexual woman, I feel hurt by that statement. I feel uncomfortable that you are disrespecting Marvin like that. I can imagine he would feel even more hurt by that statement.” |

||

|

Use an exclamation |

Tonya says “Ouch!” |

||

|

Use nonverbal communication |

Shaking head, covering mouth with hand. |

||

|

Interrupt and redirect |

Tonya says “Stop. Let’s not say things like that. Why don’t we get back to work? |

||

|

Remind them of the rules |

Sam says “Our program has made it clear that comments like that will not be tolerated. If you continue with that behavior, the diversity and inclusion officer may become involved.” |

Situation: Jade is a non-binary individual who uses they/them pronouns. They have communicated their pronouns to their cohort, and wear a pronoun pin most days. During a group project, Kevin, a male colleague, continues to refer to them as “the only girl” in the group, and continues to use she/her pronouns. Lin, a bystander in the group, may employ the following micro interventions.

|

GOAL |

OBJECTIVE |

TACTICS |

EXAMPLES |

|

Educate the offender |

Engage in a one-on-one dialogue with the perpetrator to indicate how and what they have said is offensive to you or others |

Differentiate between intent and impact |

“I know you don’t mean any harm when you refer to Jade as a girl, but they feel hurt when you misgender them.” |

|

Facilitate a possibly more enlightening conversation and exploration of the perpetrator’s biases |

Appeal to the offender’s values and principles |

“I know you value hard work. What if we put that same effort into remembering Jade’s pronouns?” |

|

|

Encourage the perpetrator to explore the origins of their beliefs and attitudes towards targets |

Point out the commonality

|

“I think your research interests align with Jade’s. Learning their pronouns and respecting their gender identity might be a good first step towards forming a good working relationship.” |

|

|

Promote empathy |

“If someone used she/her pronouns for me, even though I use he/him pronouns, I would feel upset. I’m curious if you would feel the same way? It can be painful when your identity is invalidated.” |

||

|

Point out how they benefit |

“If we treat Jade with respect, not only will they feel more respected and included within our group, but we will also have a better group environment. We can be more productive that way.” |

While advocacy and micro-interventions can be empowering, it is equally important to take care of yourself. If you have experienced microaggressions or discrimination, applying your coping skills will be critical; see the Mental Health and Wellness module for more details. Self-care also includes reaching out for support. Whether that means reaching out to friends and family, or pursuing therapy, it is important to connect with others. See the Online Resources and Supports module for information on finding LGBTQ-focused organizations.

Ackerman, N., Atherton, T., Avalani, A. R., Berven, C. A., Laskar, T., Neunzert, A., Parno, D. S., Ramsey-Musolf, M. (2018). LGBT+ inclusivity in physics and astronomy: A best practices guide. https://doi.org/arXiv:1804.08406

Budge, S. L., Domínguez, S., Jr., & Goldberg, A. E. (2020). Minority stress in nonbinary students in higher education: The role of campus climate and belongingness. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 7(2), 222–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000360

Carlone, H. B., & Johnson, A. (2007). Understanding the science experiences of successful women of color: Science identity as an analytic lens. Journal of Research and Science Teaching, 44, 1187–1218. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20237

Cech, E. A., & Waidzunas, T. J. (2011). Navigating the heteronormativity of engineering: The experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual students. Engineering Studies, 3(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19378629.2010.545065

Cooper, K. M., Auerbach, A. J. J., Bader, J. D., Beadles-Bohling, A. S., Brashears, J. A., Cline, E., ... & Brownell, S. E. (2020). Fourteen recommendations to create a more inclusive environment for LGBTQ+ individuals in academic biology. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 19(3), es6. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.20-04-0062.

Duran, A. (2019). Queer and of color: A systematic literature review on queer students of color in higher education scholarship. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 12(4), 390-400. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000084

Goldberg, A. E., Kuvalanka, K., & dickey, l. (2019). Transgender graduate students’ experiences in higher education: A mixed-methods exploratory study. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 12(1), 38-51. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000074

Hughes, B. E. (2018). Coming out in STEM: Factors affecting retention of sexual minority STEM students. Science Advances, 4(3), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aao6373

Linley, J. L., Renn, K. A., & Woodford, M. R. (2018). Examining the ecological systems of LGBTQ STEM majors. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering, 24(1) 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1615/JWomenMinorScienEng.2017018836

Miller, R. A., Vaccaro, A., Kimball, E. W., & Forester, R. (2020. “It’s dude culture”:Students with minoritized identities of sexuality and/or gender navigating STEM majors. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000171

Nadal, K. L., Whitman, C. N., Davis, L. S., Erazo, T., & Davidoff, K. C. (2016). Microaggressions toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and genderqueer people: A review of the literature. The Journal of Sex Research, 53(4-5), 488-508. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1142495

Parnell, M. K., Lease, S. H., & Green, M. L. (2012). Perceived career barriers for gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Career Development, 39(3), 248-268. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845310386730

Stout, J. G., & Wright, H. M. (2016). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer students' sense of belonging in computing: An Intersectional approach. Computing in Science & Engineering, 18(3), 24-30. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCSE.2016.45

Sue, D. W., Alsaidi, S., Awad, M. N., Glaeser, E., Calle, C. Z., & Mendez, N. (2019). Disarming racial microaggressions: Microintervention strategies for targets, White allies, and bystanders. American Psychologist, 74(1), 128-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000296

Woodford, M. R., Han, Y., Craig, S., Lim, C., & Matney, M. M. (2014). Discrimination and mental health among sexual minority college students: The type and form of discrimination does matter. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 18(2), 142-163. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2013.833882

Identify The Issue Side Menu

- Overview

- Recognize Sexism

- Recognize Microaggressions

- Family-Friendly Policies

- University Resources

- Online Resources and Supports

- Challenges Faced by Women of Color

- Challenges Faced by First-Generation Students

- Challenges Faced by Sexual and Gender Minorities

- Challenges Faced by International Students

- Academic Generations

- Expectations for Graduate Students

- Stakeholders

- Sexual Harassment

Explains that satisfaction comes from working with students and the opportunity to make new disco

Explains that satisfaction comes from working with students and the opportunity to make new disco

The importance of learning from mistakes and persisting despite setbacks.

The importance of learning from your effort, regardless of the outcome.

Advice on how to seek out support in graduate school and how to bounce back from setbacks.

Shares the excitement that comes from collaborating with others to make new discoveries.

Elaborates on the standard practice of science despite cultural differences.

Strategies for negotiating as a faculty member.

When it's time to graduate and when it's important to start learning on the job.

Highlights the transition into graduate level science where the answers aren't known.

The importance of goal setting and using others' experiences to make strong choices about your own p

Advice for balancing research and fun in graduate school.

Advice for students: stay focused, ask questions, and remain open-minded when working with others.

How to adapt experimental methods to match a lifestyle.

How to negotiate a schedule for raising a family and overcoming setbacks in a new career.

The importance of giving yourself credit and remembering why you are doing what you're doing.

The importance of peer relationships and the learning process that takes place despite concrete outc

Working with graduate students is a rewarding aspect of being a faculty member.

Advice for graduate students on how to maintain their confidence, courage, and dignity.

Emphasizes peer relationships and departmental climate.

How to handle being accused of having an affair with the advisor.

Explains an interdisciplinary branch of physics and the passion for research, service, and teaching.

Teaching as the impetus for work.

Discusses necessary precautions to take as a female student working late nights on campus.

Discusses necessary precautions to take as a female student working late nights on campus.

Being accused of cheating and regrets about not being more assertive.

Being accused of cheating and regrets about not being more assertive.

The importance of self-authorship and using graduate school as a process for self-definition.

Reminder that support can be found in unexpected places.

Urges female graduate students to persist in the field of mathematics because the field needs divers

How being unaware of being the only woman was advantageous to program success.

Alternatives to departmental isolation and the importance of networking.

Environmental issues faced in academia.

The importance of first impressions in choosing a graduate program.

Satisfaction comes from interacting with intelligent people across cultures.

Adjusting physical appearance to fit in with peers.

The importance of remembering that graduate school is only one part of a larger career.

Describes an incident of receiving a lower grade than a man for similar work.

The opportunity for freedom, growth, and collaboration as a faculty member.

How to survive the aftermath of a sexual harassment incident.

Highlights the gendered assumptions encountered as a faculty member.

The Importance of Having Positive Working Relationships: A Case Study

An alternative way to approach being the only woman in a given situation.

Contributions to the field are reflected through choices.

The importance of sharing stories of sexual harassment with others to gain support.

The importance of finding the right advisor to support your research goals.

How to handle being accused of having an affair with the advisor.

Explains when to confront a problem and when it may be better to maneuver around it.

How to be upfront, direct, and assertive when confronting instances of sexual harassment.

Highlights the universal customs of science.

Class performance builds confidence to remain in program.

Captures the annoyance of male colleagues making sexist assumptions and the challenges with conferen

The importance of recognizing the progress that has been made by women in science fields.

Advice for accomplishing your academic goals without making unnecessary compromises.

Emphasizes the challenge with saying no, but the importance of learning to do so.

How to make friends with colleagues to encourage a supportive environment.

Underscores the challenges that come from being the only woman in an academic department and gives s

Highlights an experience in which peers were not only colleagues, but also friends.

How the physical space in a laboratory allowed for collaboration among colleagues.

The importance of a good leader in setting standards for diversity, climate, and tenure policies.

How to observe others' reactions to subtle comments in order to gauge an appropriate response.

Urges students not to get wrapped into issues that do not directly involve them.

Departmental reactions to the choice to have children.

How to refute sexist comments and challenge gendered assumptions.

The importance of sharing stories of sexual harassment with others and realizing that you are not al

Confronting a male colleague with contradictory findings at a conference.

How colleagues can assist in making the transition into graduate life easier by sharing information

Captures the small but noticeable annoyances that come with being the only woman.

The importance of picking your battles to avoid unfair labeling.

Reminder that it is not necessary to feel comfortable socially to do good science.

Gender stereotypes faced in getting into graduate school and conducting research.

How to seek support from administrators outside the department when dealing with departmental sexism

The first realization that being a woman in science was outside the norm.

Challenges of being international and female, particularly with regards to an academic career and th

Suggestions for how to deal with sexist comments.

Playing a variety of roles as the only woman in the department.

The process of establishing yourself in the same department as your spouse.

Emphasizes positive peer relationships within her cohort.

The challenges of working in male-dominated academic environments and the negative stereotypes assoc

The feasibility of pursuing a family and science.

The importance of hearing other people's stories.

The importance of understanding priorities and allocating resources accordingly.

Advises how to keep family informed about research goals and progression from student to faculty mem

Explains some of the setbacks in dating relationships.

Advises students to continue to pursue their education because the payoff is self-respect.

The importance of believing in yourself, admitting your mistakes, and continuing to do what you love

How to accept non-traditional relationships and lifestyles in academia.

Notes the challenges of a dual career marriage and the obstacles in fighting for tenure and balancin

The process of overcoming setbacks related to career options and personal relationships.

How to balance motherhood responsibilities in graduate school.

The importance of supportive peer relationships.

Being married in graduate school and having children as a faculty member.

Advisor's experiences encourage well-informed career decisions.

The importance of a supportive network of colleagues.

Doing something useful to make a difference and how to appreciate a happy, supportive work environme

Taking time off before pursuing her PhD.

How a supportive department and a modified teaching schedule allowed for maternity leave.

How to sustain taking time off and pursuing the PhD later in life.

Advises how to keep family informed about research goals and progression from student to faculty mem

The importance of a supportive extended family in helping to balance school and children.

The importance of having a number of things in your life that bring you joy and satisfaction.

Understanding your strengths and weaknesses, but ultimately giving yourself recognition for your suc

The importance of learning over time and remaining positive in the face of criticism.

Motivation for doing work: interacting with students and doing research that can make a difference i

Emphasizes the challenge with saying no, but the importance of learning to do so.

The importance of remaining passionate and remembering that the PhD opens doors.

The importance of defining clear goals, remaining self-confident, and learning to say no.

The importance of allowing yourself the opportunity to change your mind and reconsider your goals.

The importance of knowing what you want and expecting tradeoffs on the path to get it.

Making discoveries and collaborating with others brings satisfaction.

Creating a schedule and meeting an advisor's expectations.

Advises graduate students to take a semester off if they choose to have a child because it is too ch

Explains the role children play in career choices.

Using leisure activities to relieve stress and build friendships.

The satisfaction that comes from working with colleagues and interacting with others.

The decision to get married in graduate school.

The importance of maintaining a balanced lifestyle to alleviate stress.

Addresses personal relationship sacrifices.

The importance of nurturing relationships outside of academia.

Explains the choice to have children in graduate school.

Challenges with being married to a fellow academician and finding faculty positions.

How a flexible schedule as a professor made it possible to have a family and a career.

The importance of evaluating your priorities to create balance and happiness.

Appreciation for advisor's assistance in transitioning to the US.

Emphasizes the joy in working with others and giving back to society.

Chronicles the evolution of a career over time.

Suggestions for how to increase women's participation in science with an emphasis on policy change.

The importance of being open and honest with your advisor.

How a positive advisor challenged his students to think for themselves.

Highlights the obstacles faced when trying to have research reviewed by the advisor and emphasizes t

The importance of having a variety of mentors throughout your graduate experience.

Challenges faced with establishing yourself as an independent researcher separate from an influentia

The importance of asking questions and searching for creative solutions to new problems.

The importance of finding a good advisor and making sure to get everything in writing.

Challenges in confronting the advisor with news of pregnancy.

Experiences with an international advisor.

How to maintain good relationships with colleagues while being motivated to finish the program qu

The importance of giving back to students and making an impact in their future education and care

An Arizona State University project, supported by the National Science Foundation under grants 0634519, 0910384 and 1761278

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. © 2021 CareerWISE. All rights reserved. Privacy | Legal

Comments

We want to hear from you. Did this page remind you of any experiences you’ve had? Did you realize something new? Please take a moment to tell us about it—and we’ll keep it confidential.