Identify the issue

Career Wise Menu

Understand the Context: Challenges Faced by Women of Color

- Learn how marginalizing STEM environments affect graduate Women of Color

- Learn tools to protect yourself from experiences of racism and sexism

- Learn how to dismantle microaggressions

“There was at least one person in my cohort who jokingly said, essentially, that I only got into the program because I was a Black woman. ... it was just like another stab at that confidence, like you don’t actually belong here. You’re only here to fill the quota.”

“I remember personally one of my PIs rotation, he stopped me in the middle of a presentation to correct me on how to say a word, like, ‘We don’t say that word. That’s not how you say it. This is how you say it’… It caught me off guard. And it didn’t only happen to me. It happened to my friends, like I said, one of the girls from [country in Asia], she was told in her feedback, ‘Oh, you need to improve your English. It’s very distracting.”

“Having come up through my undergrad program where it was drilled into us how important it is to have this minority PhD pipeline and how gruesome the statistics are on Black representation, that was a motivator for me not to [leave]. Because we need women, like Black women PhDs, like we need those… That was something that I was afraid [of] and like, ‘Oh, I’ve let down the culture.’”

The chilly and unwelcoming nature of STEM environments has historically served to ostracize Women of Color, undermine their confidence in themselves as STEM professionals, and used stereotypes and other discriminatory tactics to challenge their belonging and right to exist in those spaces.

In fact, of the undergraduate women enrolled in STEM majors, Black and Latinx women leave their degree programs at higher rates than their White counterparts: 40% for Black women, 37% for Latinx women, and 20% for White women (NSF, 2017). In 2015, the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) reported that the percentage of Women of Color who attended graduate school STEM degree programs was as follows: Asian women (5%), Black women (2.9%), and Latinx women (3.8%).

For Women of Color in STEM doctoral programs, the seven-year attrition rate is 34%, and more than half of this subset of women discontinue their STEM degree programs within the first two-years (Sowell et al, 2015). In 2016, only 7.8% of master’s degrees in science and engineering, and 5% of doctorate degrees in science and engineering were awarded to women from racial- and ethnic-minority backgrounds (NSF, 2015).

Despite decades of efforts to increase parity in STEM, these statistics indicate that Women of Color remain significantly underrepresented in STEM.

Efforts to address the inequitable representation of diverse students in STEM tend to focus on women and minorities. However, such a focus renders invisible the ways in which these two social groups intersect, as they do in the lives of Women of Color.

Researchers regard this focus on “women and minorities” as the “ampersand problem” (Bowleg, 2012). The focus on “women and minorities” not only implies a universally gendered and racialized experience but also promotes the belief that solutions are equally applicable to all women and People of Color, when that is not the case.

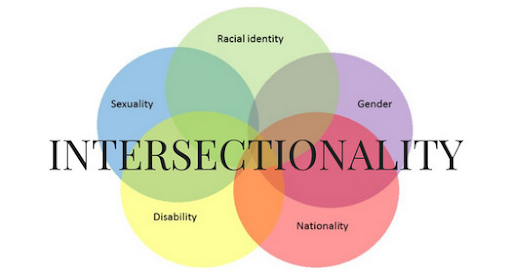

Black feminst scholars have worked to make explicit the ways in which social inequality, in conjunction with power and privilege, are shaped by many interlocking systems that directly influence each other. The terms Intersectionality, Gendered Racism, and the Double Bind (in STEM) provide frameworks to assist in rendering these marginalized experiences visible.

Intersectionality

The term “intersectionality” was coined by American lawyer and activist Kimberlé Crenshaw (1991) to describe the ways in which systems of power and oppression impact individuals’ lived experiences based on their intersecting social identities. Social group identities may include:

- Age

- Race or Ethnicity

- Class

- Religion

- Ability

- Sexuality

- Gender

- Citizenship

See here for source.

For example, it is often cited that women make less money than men. Looking closer, the data tells a more nuanced story: White women earn more than Black men, and Black men earn more than Latinx and Black women. Taking an intersectional approach to understanding inequities helps us understand these disparities in a more nuanced way.

Gendered Racism

Gendered racism was first coined by sociologist Philomena Essed (1991) and was used to describe the reproduction of institutional racism through various facets and arenas in a person’s everyday life. It is a form of oppression that occurs as a product of a person’s race and gender identities, or the intersecting experience of racism and sexism experienced by Women of Color. Studies have found that repeated experiences of gendered racism have been significantly related to Black women’s psychological distress.

The Double Bind

In STEM contexts specifically, Shirley Malcom, Paula Hall, and Janet Brown (1975) were the first to call attention to the simultaneous experiences of both sexism and racism faced by Women of Color. These scholars characterized this unique intersectional experience as the ‘double bind.’ The double bind is noteworthy becuase it sheds light on how Women of Color in STEM experience prejudice and discrimination both as women and as People of Color, within a predominantly White and masculine STEM environment.

By understanding these three concepts - Intersectionality, Gendered Racism, and the Double Bind - you can see how the impact of these marginalizing encounters exacerbates what constitutes the “chilly” STEM climate for Women of Color.

Adopting an intersectional approach allows us to understand that graduate Women of Color bring their full selves, and therefore multiple intersecting identities, into classrooms and laboratories. What occurs outside in the world as well as inside the STEM environment has the potential to impact their experience.

Women of Color not only contend with systemic acts of hate in the larger society, but must also navigate the chilly STEM climate which is replete with further oppressive and marginalizing acts. In this section, we will highlight the systemic and structural barriers that occur both inside and outside of the STEM environment to provide insight into the multiplicative toll of how structural racism impacts graduate Women of Color.

Systemic and Structural Barriers Inside STEM

- Hypervisibility & Invisibility - Navigating gendered experiences in a male dominated environment can contribute to women feeling hyper-aware of their gender. For Women of Color, there is a heightened awareness of not only their gender, but also their race. Navigating both racialized and gendered experiences in STEM has simultaneously rendered Women of Color as both invisible and hypervisible.

As it relates to invisibility, Women of Color in STEM are often discredited as future scientists, and instead viewed as representatives of their race and gender. Being regarded as only a representative of one’s race and gender can take a substantial toll. For example, Women of Color frequently reported that, as a result of feeling like “the only one” with respect to their racial and gender identity, they felt an immense amount of pressure to succeed and function in STEM spaces. Many worried that if they failed to succeed, their STEM programs would likely think twice about admitting other Women of Color into the program (Wilkins-Yel, et al., 2019).

Although Women of Color were not seen as emerging scientists, they were often one of a few, if not the only, Women of Color in their labs and departments. This status as a “solo,” rendered them hypervisible to scrutiny and marginalization. For example, Women of Color reported feeling “surveilled” by their male peers and negatively judged due to assumptions that they are intellectually inferior (Ong et al., 2011). So, Women of Color must contend with the stressors of being scrutinized (hypervisibility) but not recognized (invisibility) (Settles, Buchanan, et al., 2019).

- Gender-, Racial-, and Gendered-Racial Microaggressions - Women of Colors’ educational experiences are constantly hampered by often nuanced encounters of marginalization in STEM spaces. In the 1970s, American psychiatrist Chester Pierce (1978) coined the term microaggression to describe these discriminatory experiences.

According to Pierce, microaggressions are “subtle, stunning, often automatic and nonverbal exchanges that are ‘put-downs’ of Blacks by offenders”. Over time, the term microaggression has evolved and now encapsulates any subtle manifestations of bias or negative attitudes that are directed towards people who hold marginalized identities. Thus, a microaggression can be a subtle slight made towards a person on the basis of their race, as in the case of People of Color, gender, as it relates to women, and gendered-racial microaggressions, as in the case of Women of Color.

Racial microaggression. Derald Wing Sue, a renowned counseling psychologist, built on Pierce’s (1978) early work on microaggressions to describe racial microaggressions specifically. He defined these acts as “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color” (Sue et al., 2007). An example of a racial microaggression is assuming that a Person of Color in an office building is a custodial worker. Such an assumption implies that the person is not qualified enough to work in any other position but that of a custodian.

Gender microaggression. Similar to a racial microaggression, a gender microaggression is any brief, nuanced, everyday exchange that communicates sexist ideas that unfairly criticize women (Capodilupo, et al., 2010). A common gender microaggression that occurs in STEM is when men talk over women or dismiss her ideas only to think that they are valid when they have been shared by a colleague. These behaviors imply that a woman’s contributions are less valid than her male counterparts.

Gendered-Racial microaggressions. Both racial microaggressions and gender microaggressions fail to account for the intersectional ways in which microaggressions are enacted. Consequently, counseling psychologist Jioni Lewis coined the term gendered-racial microaggressions and defined it as, “subtle and everyday verbal, behavioral, and environmental expressions of oppression based on the intersection of one’s race and gender” (Lewis et al., 2013, p. 51). An example of a gendered-racial microaggression is perceiving a Black woman’s response to an issue as ‘angry’ because of how she may have spoken. This perception stifles a Black woman’s ability to engage in the full range of expressing herself.

Please see the Microaggressions module for more on these topics.

Systemic and Structural Barriers Outside STEM

Anti-Black racism and police brutality are contemporary and historical sources of trauma in Black communities. Although this violence plagues both Black men and women, what happens to Black women receives far less public outcry. In essence, their pain and trauma are rendered invisible by overwhelming silence (Hargons et al., 2017). Therefore, when Black women are situated in STEM spaces where they are significantly underrepresented, they are forced to carry these social burdens and their related traumas into the classroom. The cumulative toll of this burden can pose a risk to the totality of Black women’s educational experiences. The quote below is from a Black woman in engineering who ultimately decided to discontinue her PhD. Here, she describes what it was like to be bombarded with images and news pieces about the killing of Black people and feeling like this pain was invisible to those in her lab:

While I was in grad school, there was a huge up-swelling of instances where unarmed black people were being gunned down by police. It was something that was always on my social media. I felt like just because of what I looked like and who I was affiliated with, I didn't matter… I didn't feel like [my peers] empathized or could really understand what it felt like to feel so insignificant, even though we're both pursuing the same type of degree.

In response to the uptick in murders of Black people in the United States, STEM communities generated the #ShutDownSTEM hashtag, which was instituted on June 10th, 2020 as a massive shutdown to academia. #ShutDownSTEM was also an effort to challenge the institutional racism that had similarly threatened the lives of Black people in STEM who had been obliged to continue with “business as usual” while such rampant injustice towards Black lives was taking place. On this day, Black Academics and Black STEM professionals were encouraged to tend to themselves, their emotional needs, take time to rest, or find ways to take action that was safe for them, while non-Black persons were encouraged to educate themselves about how they could help to eliminate racism.

Further, the ongoing COVID-19 global pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on communities of color, which means that graduate Women of Color are at an increased likelihood of having family members who have passed due to the virus, or have fallen ill and are in need of care.

These are just some examples of the systemic and structural barriers that lie both inside and outside of STEM that inevitably contribute to graduate Women of Color’s wellbeing and ability to persist.

- Lean into your social support, particularly shared-identity support spaces -

- Find others who intimately understand what you are going through, and who can provide emotional solace when you are discussing negative experiences related to race and culture.

- Counterspaces in STEM are often considered “safe spaces'' for underrepresented groups, such as Women of Color. These shared-identity support spaces allow underrepresented students the opportunity to receive validation of their critical knowledge and experiences, vent frustrations by sharing stories of isolation, microaggressions, and other forms of discrimination, while also creating and maintaining a positive racial climate for themselves (Ong, Smith, et al, 2017).

- Externalize the impact -

- Externalizing microaggressive encounters can minimize the degree to which one internalizes the impact of microaggressions. Here are some examples of how you can externalize the assault when you are the target of microaggressions:

- Microaggression: I am mistaken for someone else of the same racial background.

- Externalizing reframe: I have and will continue to build a powerful sense of self that strengthens me.

- Microaggression: Others characterize me as “angry”

- Externalizing reframe: I critically question and reject negative stereotypes and society’s lowered expectations of BIPOC leaders.

- Microaggression: Others regularly take credit for my ideas in meetings.

- Externalizing reframe: At times, I experience painful bias, but I do not let these microaggressions limit my career. Instead of shutting down or quitting, I choose to seek the support of my colleagues in making my workplace more inclusive.

- Microaggression: I am mistaken for someone else of the same racial background.

- In addition to the above examples of ways to externalize microaggressions, remember that the intent behind a microaggressive comment does not negate the mental, emotional, or psychological impact that such a comment has on you. So, know that, regardless of the perpetrators’ intent, your feelings are valid and you have the right to respond in the manner you see fit - whether that is immediately, later, or not at all.

- Externalizing microaggressive encounters can minimize the degree to which one internalizes the impact of microaggressions. Here are some examples of how you can externalize the assault when you are the target of microaggressions:

- Own and validate your identity as an emerging scientist in your respective program. So, decrease the tendency to preface comments with phrases like “I think” or “I am not sure, but…” to boost [your] own confidence in [your] identity.

- Confront racism directly or indirectly

- Confronting racism, either directly or indirectly, can feel challenging, nerve wracking, intimidating, and at times, even painful. In recognition of this, a person can ask themselves any of the following questions before making the decision to confront racism (Nadal, 2014):

- If I respond, could my physical safety be in danger?

- If I respond, will the person become defensive and will this lead to an argument?

- If I respond, how will this affect my relationship with this person (e.g., co-worker, family member, faculty member, etc.)

- If I don’t respond, will I regret not saying something?

- If I don’t respond, does that convey that I accept the behavior or statement?

- Confronting racism, either directly or indirectly, can feel challenging, nerve wracking, intimidating, and at times, even painful. In recognition of this, a person can ask themselves any of the following questions before making the decision to confront racism (Nadal, 2014):

- Promote awareness of and access to counterspaces (e.g. graduate student networks and caucuses, STEM diversity conferences, churches and spiritual communities; Ong, Smith & Ko, 2017)

- Provide anti-racist training to faculty and staff

- Provide opportunities and resources for students to connect with persons in authority and develop mentoring relationships across departments and disciplines.

- Disrupt racist and sexist comments in the classroom and the lab

- Recognize the signs of psychological stress (e.g. anxiety, depression) that can come with racial battle fatigue. Normalize help seeking behaviors (See Mental Health module)

- Validate graduate Women of Color’s belonging with written and verbal encouragement

- Use self-disclosure to help combat the impact of imposter syndrome by sharing similar experiences from your own graduate studies

- Readily ask students what they are doing to prioritize their wellbeing, and share things you have done for yourself to promote a culture of care and work/life balance

By applying an intersectional framework to the challenges faced by graduate Women of Color in STEM, you can better see how structural barriers both within and outside the STEM setting have the potential to negatively influence your experiences.

Use this intersectional framework to contextualize the challenges you might face in your graduate program, and use the tools and strategies presented here to minimize the degree to which you internalize these structural and systemic problems.

Bowleg, L. (2012). The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1267–1273. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750

Capodilupo, C. M., Nadal, K. L., Corman, L., Hamit, S., Lyons, O. B., & Weinberg, A. (2010). The manifestation of gender microaggressions. Microaggressions and marginality: Manifestation, dynamics, and impact. 193-216.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Essed, P. (1991).Understanding everyday racism: An interdisciplinary theory (Vol. 2). Sage series on race and ethnic relations: Vol. 2. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Hargons, C., Mosley, D., Falconer, J., Faloughi, R., Singh, A., Stevens-Watkins, D., & Cokley, K. (2017). Black Lives Matter: A call to action for counseling psychology leaders. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(6), 873–901. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000017733048

Lewis, J. A., Mendenhall, R., Harwood, S. A., & Browne Huntt, M. (2013). Coping with Gendered Racial Microaggressions among Black Women College Students. Journal of African American Studies, 17(1), 51-73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-012-9219-0

Malcolm, S. M., Brown, J. W., & Hall, P. Q. (1976). The double bind: the price of being a minority woman in science: Report of a conference of Minority Women Scientists. American Association for the Advancement of Science. https://web.mit.edu/cortiz/www/Diversity/1975-DoubleBind.pdf

Nadal, K. (2014). A guide to responding to microaggressions. CUNY Forum, 2(1), 71-76. https://advancingjustice-la.org/sites/default/files/ELAMICRO%20A_Guide_…

National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. 2017. Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering: 2017. Special Report NSF 17-310. Arlington, VA. Available at www.nsf.gov/statistics/wmpd/.

Ong, M., Smith, J. M., & Ko, L. T. (2017). Counterspaces for women of color in STEM higher education: Marginal and central spaces for persistence and success. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 55(2), 206–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21417

Ong, M., Wright, C., Espinosa, L., & Orfield, G. (2011). Inside the double bind: a synthesis of empirical research on undergraduate and graduate Women of Color in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Harvard Educational Review, 81(2), 172–209. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.81.2.t022245n7x4752v2

Pierce, C., Carew, J., Pierce-Gonzalez, D., & Willis, D. (1978). An experiment in racism: TV commercials. In C. Pierce (Ed.), Television and education (pp. 62–88). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. https://doi.org/10.1177/001312457701000105

Primé, D.R., Bernstein, B.L., Wilkins, K.G., & Bekki, J.M. (2015). Measuring the advising alliance for female graduate students in science and engineering: An emerging structure. Journal of Career Assessment, 23(1), 64-78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072714523086

Settles, I. H., Buchanan, N. C. T., & Dotson, K. (2019). Scrutinized but not recognized: (In)visibility and hypervisibility experiences of faculty of color. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 113, 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.06.003

Sowell, R., Allum, J., & Okahana, H. (2015). Doctoral initiative on minority attrition and completion. Washington, DC: Council of Graduate Schools.

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271

Truong, K., & Museus, S. (2012). Responding to racism and racial trauma in doctoral study: An inventory for coping and mediating relationships. Harvard Educational Review, 82(2), 226-254. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.82.2.u54154j787323302

Wilkins-Yel, K. G., Hyman, J., & Zounlome, N. O. (2019). Linking intersectional invisibility and hypervisibility to experiences of microaggressions among graduate women of color in STEM. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 113, 51-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.10.018

Identify The Issue Side Menu

- Overview

- Recognize Sexism

- Recognize Microaggressions

- Family-Friendly Policies

- University Resources

- Online Resources and Supports

- Challenges Faced by Women of Color

- Challenges Faced by First-Generation Students

- Challenges Faced by Sexual and Gender Minorities

- Challenges Faced by International Students

- Academic Generations

- Expectations for Graduate Students

- Stakeholders

- Sexual Harassment

Explains that satisfaction comes from working with students and the opportunity to make new disco

Explains that satisfaction comes from working with students and the opportunity to make new disco

The importance of learning from mistakes and persisting despite setbacks.

The importance of learning from your effort, regardless of the outcome.

Advice on how to seek out support in graduate school and how to bounce back from setbacks.

Shares the excitement that comes from collaborating with others to make new discoveries.

Elaborates on the standard practice of science despite cultural differences.

Strategies for negotiating as a faculty member.

When it's time to graduate and when it's important to start learning on the job.

Highlights the transition into graduate level science where the answers aren't known.

The importance of goal setting and using others' experiences to make strong choices about your own p

Advice for balancing research and fun in graduate school.

Advice for students: stay focused, ask questions, and remain open-minded when working with others.

How to adapt experimental methods to match a lifestyle.

How to negotiate a schedule for raising a family and overcoming setbacks in a new career.

The importance of giving yourself credit and remembering why you are doing what you're doing.

The importance of peer relationships and the learning process that takes place despite concrete outc

Working with graduate students is a rewarding aspect of being a faculty member.

Advice for graduate students on how to maintain their confidence, courage, and dignity.

Emphasizes peer relationships and departmental climate.

How to handle being accused of having an affair with the advisor.

Explains an interdisciplinary branch of physics and the passion for research, service, and teaching.

Teaching as the impetus for work.

Discusses necessary precautions to take as a female student working late nights on campus.

Discusses necessary precautions to take as a female student working late nights on campus.

Being accused of cheating and regrets about not being more assertive.

Being accused of cheating and regrets about not being more assertive.

The importance of self-authorship and using graduate school as a process for self-definition.

Reminder that support can be found in unexpected places.

Urges female graduate students to persist in the field of mathematics because the field needs divers

How being unaware of being the only woman was advantageous to program success.

Alternatives to departmental isolation and the importance of networking.

Environmental issues faced in academia.

The importance of first impressions in choosing a graduate program.

Satisfaction comes from interacting with intelligent people across cultures.

Adjusting physical appearance to fit in with peers.

The importance of remembering that graduate school is only one part of a larger career.

Describes an incident of receiving a lower grade than a man for similar work.

The opportunity for freedom, growth, and collaboration as a faculty member.

How to survive the aftermath of a sexual harassment incident.

Highlights the gendered assumptions encountered as a faculty member.

The Importance of Having Positive Working Relationships: A Case Study

An alternative way to approach being the only woman in a given situation.

Contributions to the field are reflected through choices.

The importance of sharing stories of sexual harassment with others to gain support.

The importance of finding the right advisor to support your research goals.

How to handle being accused of having an affair with the advisor.

Explains when to confront a problem and when it may be better to maneuver around it.

How to be upfront, direct, and assertive when confronting instances of sexual harassment.

Highlights the universal customs of science.

Class performance builds confidence to remain in program.

Captures the annoyance of male colleagues making sexist assumptions and the challenges with conferen

The importance of recognizing the progress that has been made by women in science fields.

Advice for accomplishing your academic goals without making unnecessary compromises.

Emphasizes the challenge with saying no, but the importance of learning to do so.

How to make friends with colleagues to encourage a supportive environment.

Underscores the challenges that come from being the only woman in an academic department and gives s

Highlights an experience in which peers were not only colleagues, but also friends.

How the physical space in a laboratory allowed for collaboration among colleagues.

The importance of a good leader in setting standards for diversity, climate, and tenure policies.

How to observe others' reactions to subtle comments in order to gauge an appropriate response.

Urges students not to get wrapped into issues that do not directly involve them.

Departmental reactions to the choice to have children.

How to refute sexist comments and challenge gendered assumptions.

The importance of sharing stories of sexual harassment with others and realizing that you are not al

Confronting a male colleague with contradictory findings at a conference.

How colleagues can assist in making the transition into graduate life easier by sharing information

Captures the small but noticeable annoyances that come with being the only woman.

The importance of picking your battles to avoid unfair labeling.

Reminder that it is not necessary to feel comfortable socially to do good science.

Gender stereotypes faced in getting into graduate school and conducting research.

How to seek support from administrators outside the department when dealing with departmental sexism

The first realization that being a woman in science was outside the norm.

Challenges of being international and female, particularly with regards to an academic career and th

Suggestions for how to deal with sexist comments.

Playing a variety of roles as the only woman in the department.

The process of establishing yourself in the same department as your spouse.

Emphasizes positive peer relationships within her cohort.

The challenges of working in male-dominated academic environments and the negative stereotypes assoc

The feasibility of pursuing a family and science.

The importance of hearing other people's stories.

The importance of understanding priorities and allocating resources accordingly.

Advises how to keep family informed about research goals and progression from student to faculty mem

Explains some of the setbacks in dating relationships.

Advises students to continue to pursue their education because the payoff is self-respect.

The importance of believing in yourself, admitting your mistakes, and continuing to do what you love

How to accept non-traditional relationships and lifestyles in academia.

Notes the challenges of a dual career marriage and the obstacles in fighting for tenure and balancin

The process of overcoming setbacks related to career options and personal relationships.

How to balance motherhood responsibilities in graduate school.

The importance of supportive peer relationships.

Being married in graduate school and having children as a faculty member.

Advisor's experiences encourage well-informed career decisions.

The importance of a supportive network of colleagues.

Doing something useful to make a difference and how to appreciate a happy, supportive work environme

Taking time off before pursuing her PhD.

How a supportive department and a modified teaching schedule allowed for maternity leave.

How to sustain taking time off and pursuing the PhD later in life.

Advises how to keep family informed about research goals and progression from student to faculty mem

The importance of a supportive extended family in helping to balance school and children.

The importance of having a number of things in your life that bring you joy and satisfaction.

Understanding your strengths and weaknesses, but ultimately giving yourself recognition for your suc

The importance of learning over time and remaining positive in the face of criticism.

Motivation for doing work: interacting with students and doing research that can make a difference i

Emphasizes the challenge with saying no, but the importance of learning to do so.

The importance of remaining passionate and remembering that the PhD opens doors.

The importance of defining clear goals, remaining self-confident, and learning to say no.

The importance of allowing yourself the opportunity to change your mind and reconsider your goals.

The importance of knowing what you want and expecting tradeoffs on the path to get it.

Making discoveries and collaborating with others brings satisfaction.

Creating a schedule and meeting an advisor's expectations.

Advises graduate students to take a semester off if they choose to have a child because it is too ch

Explains the role children play in career choices.

Using leisure activities to relieve stress and build friendships.

The satisfaction that comes from working with colleagues and interacting with others.

The decision to get married in graduate school.

The importance of maintaining a balanced lifestyle to alleviate stress.

Addresses personal relationship sacrifices.

The importance of nurturing relationships outside of academia.

Explains the choice to have children in graduate school.

Challenges with being married to a fellow academician and finding faculty positions.

How a flexible schedule as a professor made it possible to have a family and a career.

The importance of evaluating your priorities to create balance and happiness.

Appreciation for advisor's assistance in transitioning to the US.

Emphasizes the joy in working with others and giving back to society.

Chronicles the evolution of a career over time.

Suggestions for how to increase women's participation in science with an emphasis on policy change.

The importance of being open and honest with your advisor.

How a positive advisor challenged his students to think for themselves.

Highlights the obstacles faced when trying to have research reviewed by the advisor and emphasizes t

The importance of having a variety of mentors throughout your graduate experience.

Challenges faced with establishing yourself as an independent researcher separate from an influentia

The importance of asking questions and searching for creative solutions to new problems.

The importance of finding a good advisor and making sure to get everything in writing.

Challenges in confronting the advisor with news of pregnancy.

Experiences with an international advisor.

How to maintain good relationships with colleagues while being motivated to finish the program qu

The importance of giving back to students and making an impact in their future education and care

An Arizona State University project, supported by the National Science Foundation under grants 0634519, 0910384 and 1761278

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. © 2021 CareerWISE. All rights reserved. Privacy | Legal

Comments

We want to hear from you. Did this page remind you of any experiences you’ve had? Did you realize something new? Please take a moment to tell us about it—and we’ll keep it confidential.